Medicaid Cost-Savings Opportunities …

Medicaid Cost-Savings Opportunities

February 3, 2011

Overview

Medicaid is a large and diverse health care coverage program. Jointly financed by the States and the Federal government, in 2010, Medicaid covered nearly 53 million people and accounted for about 16 percent of all health care spending.(1) It accounts for 17 percent of all hospital spending and is the single largest source of coverage for nursing home care, for childbirth, and for people with HIV/AIDS.(2) It covers one out of four children in the nation as well as some people with the most significant medical needs.(3) While children account for most of the beneficiaries, they comprise only 20 percent of the spending. By contrast, the elderly and people with disabilities account for 18 percent of enrollees but 66 percent of the costs.(4)

Over the past three years, despite rising enrollment due to the economic recession, nationwide State spending on the Medicaid program dropped by 13.2 percent (equivalent to a 10.3 percentage point decline in the State share of the total costs of the program) as a result of the added Federal support provided to State Medicaid programs through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (the Recovery Act).(5) In 2009 alone, due to this action, State Medicaid spending fell by 10 percent even though enrollment in Medicaid climbed by 7 percent due to the recession.(6) However, this enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) support is set to expire on June 30, 2011. While State revenues are beginning to show signs of recovery, the upcoming State fiscal year could be especially difficult for States.

Against this backdrop, States are beginning to plan for 2014 when Medicaid will be simplified and expanded to adults and children with income up to 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) ($26,645 in annual income for a family of three in 2011). Benefits for most newly eligible adults will be comparable to that of typical private insurance. Significantly, almost all of the new Medicaid coverage costs will be borne by the Federal government. The Medicaid changes in the Affordable Care Act will also bring about major improvements in the program for States, health care providers, and low-income individuals. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), in collaboration with States, has been engaged in a multi-faceted process to accomplish these changes by 2014. The objective is to ensure that Medicaid functions as a high-performing program serving the needs of America’s most vulnerable citizens and is a full partner with the Health Insurance Exchanges in achieving the coverage, quality and cost containment goals of the new law. Recent reports have found that the increased support for Medicaid, lower uncompensated care costs, and other provisions of the new law to tackle health care costs will produce savings to States as they become fully effective. In the short term, however, State budget pressures are forcing an immediate focus on this program whose enrollment has grown as job-based insurance declined due to the recession.

Now HHS is stepping up its efforts to help States consider policies that will improve care and generate efficiencies, in the short term and over time, as part of the larger imperative to tackle health care cost growth throughout the health care system. This paper identifies existing flexibility in the Medicaid program and new initiatives, many of which can be accomplished under either current program flexibilities or the new options under the Affordable Care

Existing Areas of Program Flexibility

Over time, Medicaid has evolved to offer States considerable flexibility in the management and design of the program. States set provider payment rates and have considerable flexibility to establish the methods for payment, to design the benefits for adults, and to establish other program design features. In addition, States have the ability to apply for a Section 1115 waiver of other Federal requirements to adjust coverage and payment rules.(7)

1. Cost Sharing

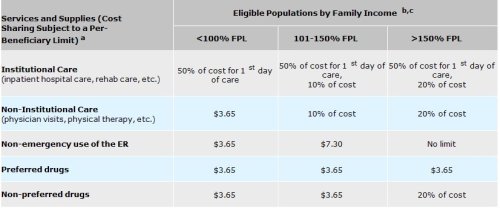

In the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, Congress gave States additional flexibility to impose cost sharing in Medicaid in the form of copayments, deductibles, coinsurance, and other similar charges without requiring States to seek Federal approval of a waiver. Certain vulnerable groups are exempt from cost sharing, including most children and pregnant women, and some services are also exempt. However, States may impose higher cost sharing for many targeted groups of somewhat higher-income beneficiaries, above 100 percent of the poverty level (the equivalent of $18,530 in annual income for a family of three), as long as the family’s total cost sharing (including cost sharing and premiums) does not exceed five percent of their income.

States may impose cost sharing on most Medicaid-covered services, both inpatient and outpatient, and the amounts that can be charged vary with income. In addition, Medicaid rules give States the ability to use cost-sharing to promote the most cost-effective use of prescription drugs. To encourage the use of lower-cost drugs, such as generics, States may establish different copayments for non-preferred versus preferred drugs. For people with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty level, cost sharing for non-preferred drugs may be as high as 20 percent of the cost of the drug. The following table describes the maximum allowable copayment amounts for different types of services.

MAXIMUM ALLOWABLE COPAYMENTS

a. Emergency services, family planning, and preventive services for children are exempt from copayments. Cost sharing is subject to a limit of five percent of income.

b. Some groups of beneficiaries, including most children, pregnant women, terminally ill individuals, and most institutionalized individuals, are exempt from copayments except nominal copayments for non-emergency use of an emergency room and non-preferred drugs. American Indians who receive services from the Indian Health Service, tribal health programs, or contract health service programs are exempt from all copayments.

c. Under certain circumstances for beneficiaries with income above 100 percent of FPL, States may deny services for nonpayment of cost sharing.

Because Medicaid covers particularly low-income and often very sick patients, Medicaid cost sharing is subject to an overall cap. The Medicaid cost for one inpatient hospital visit averages more than $5,700 for blind and disabled beneficiaries.(8) Someone in very frail health, such as a beneficiary with advanced Lou Gehrig’s disease, likely requires multiple hospital visits each year. If such an individual has four hospital stays per year and income amounting to 160 percent of poverty (about $23,000 for a family of two), without the cap he could be charged hospital cost sharing averaging up to $1,140 per visit. Total cost sharing is capped at five percent of income, so this beneficiary would not be required to pay the full 20 percent copayment for such a costly hospital stay, but could still face more than $1,100 in cost sharing per year.

Benefits

States have various sources of flexibility with respect to the design of Medicaid benefits for adults. For children, any limitations on services (either mandatory or optional) must be based solely on medical necessity; States are required to cover their medically necessary services.

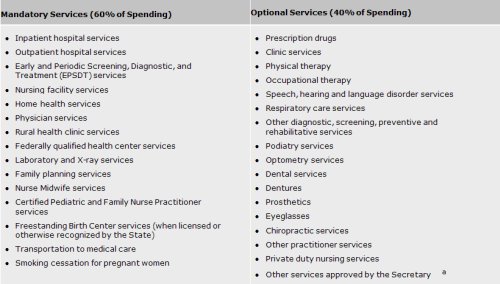

“Optional” benefits. Medicaid-covered benefits are broken out into “mandatory” services, which must be included in every State Medicaid program for all beneficiaries (except if waived under a Section 1115 waiver), and “optional” services which may be covered at the State’s discretion. Below is a table listing mandatory and optional services. While considered “optional,” some services like prescription drugs are covered by all States. In 2008, roughly 40 percent of Medicaid benefits spending – $100 billion – was spent on optional benefits for all enrollees, with nearly 60 percent of this spending for long-term care services(9)

MEDICAID COVERED SERVICES

a. This includes home and community-based care and other community-based long-term care services, coverage of organ transplants, Intermediate Care Facilities for Persons with Mental Retardation (ICF/MR) services and other services.

Amount, duration and scope of a benefit. States have flexibility in the design of the particular benefit or service for adults, so long as each covered service is sufficient in amount, duration and scope to reasonably achieve its purpose.

“Benchmark benefits.” States have broad flexibility to vary the benefits they provide to certain adult enrollees through the use of alternative benefit packages called “benchmark” or “benchmark-equivalent” plans. These plans may be offered in lieu of the benefits covered under a traditional Medicaid State plan. A benchmark benefit package can be tailored to the specific medical conditions of enrollees and may vary in different parts of a State.

Benchmark benefits coverage is health benefits coverage that is equal to the coverage under one or more of the following standard commercial benefit plans:

– Federal employee health benefit coverage – a benefit plan equivalent to the standard Blue Cross/Blue Shield preferred provider plan offered to Federal employees;

– State employee health benefit coverage – a benefit plan offered and generally available to State employees in the State; or

– Health maintenance organization (HMO) coverage – a benefit plan offered through an HMO with the largest insured commercial non-Medicaid enrolled population in the State.

States may also offer health benefit coverage through two additional types of benchmark benefit plans, Secretary-approved coverage or benchmark-equivalent plan coverage. Secretary-approved coverage is any other health benefits coverage that the Secretary determines provides appropriate coverage to meet the needs of the population provided that coverage. Benchmark-equivalent coverage is a plan with different benefits, but with an actuarial value equivalent to one of the three standard benchmark plans. Benchmark-equivalent packages must include certain services such as inpatient and outpatient hospital services, physician services, and prescription drugs.

States have the option to limit coverage for generally healthy adults to benchmark or benchmark-equivalent coverage. Other groups, including blind and disabled, medically frail, and institutionalized individuals can be offered enrollment in a benchmark plan, but they cannot be required to enroll in such a plan. To date, 11 States have approved benchmark coverage. States generally have used this option to provide benefits to targeted groups of beneficiaries, rather than having to provide these services to a broader group of people. For example, Wisconsin provides benefits equivalent to the largest commercial plan offered in the State plus mental health and substance disorder coverage for pregnant women with income between 200 and 250 percent of poverty

Opportunities for Medicaid Efficiencies

Medicaid costs per enrollee, like those in the health system generally, are driven by utilization and payment rates, including rising prices, and to some degree by waste, fraud, and abuse. Medicaid costs are also uniquely driven by increased utilization associated with the complex cases and chronic illness prevalent among those enrolled in the program. The initiatives below aim to help States improve care and lower costs largely through changes in care delivery systems and payment methodologies focused on the costs drivers in the program. We are developing a portfolio of approaches that would be combined with technical support and fast-track ways for States to implement the new initiatives and we remain open to other ideas that can improve care and efficiency. Most of these initiatives can be accomplished under current flexibilities under the program.

1. Service Delivery Initiatives and Payment Strategies for Enrollees with High Costs

Because Medicaid serves people with significant medical needs (including but not limited to “dual eligibles”) and is the largest single payer for long term care, Medicaid expenditures are driven largely by the relatively small number of people with chronic and disabling conditions. For example, in 2008, five percent of beneficiaries accounted for more than half of all Medicaid spending and one percent of beneficiaries accounted for 25 percent of all expenditures.(10) Working to develop better systems of care for these individuals holds great promise not only to improve care but to reduce costs. Reducing the average cost of care by just ten percent for the five percent of beneficiaries who are the highest users of care, could save $15.7 billion in total Medicaid spending and produce a significant positive impact on longer term spending trends.(11)

Some initiatives focusing on high-need beneficiaries include:

– Care and payment models for children’s hospitals to reorganize and refinance the way care is delivered for children with severe chronic illnesses. A number of children’s hospitals are working to coordinate all primary care and specialized care needs of these children through a medical home model. For example, St. Joseph’s Children’s Hospital of Tampa reduced emergency room visits by more than one-third, and hospital days by 20 percent. The Arkansas Children’s Hospital model is projected to reduce annual per child costs by more than 30 percent and reduce hospital admissions by 40 percent.(12) Even more importantly, the overall quality of life for these children can be dramatically improved through a medical home model of care.

– The “Money Follows the Person” demonstration grants extended and expanded under the Affordable Care Act. Currently, 43 States and the District of Columbia are using or planning to use these funds to help transition people from costly nursing home settings to more integrated community settings. HHS is currently exploring innovative ways for States to use these funds and welcomes State ideas. Promoting alternatives for home and community-based services reduces dependence on institutional care, improves the quality of life, and enhances beneficiary choice.

– Initiatives to change care and payment models to reduce premature births. Given that Medicaid currently finances about 40 percent of all births in the U.S., it has a major role to play in improving maternity care and birth outcomes. Early deliveries are associated with an increase in premature births and admissions to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), which carry a high economic cost.(13) One factor contributing to premature births is an increase in births by elective cesarean section. Promising models to reduce premature births and medically unnecessary cesarean sections include adopting new protocols and using mid-level providers in an integrated care delivery setting to improve care coordination. In New York, one model of coordinated prenatal care reduced the chances of a mother giving birth to a low-birth weight infant by 43 percent in an intervention group as compared with a group of women receiving care under standard practices.(14) In Ohio, a focus on lowering the rate of non-medically necessary pre-term cesarean deliveries has led to reductions in pre-term cesarean births and NICU admissions.(15) According to some analyses, a NICU admission increases costs ten-fold above normal delivery costs. These service delivery and payment initiatives can be accomplished without a waiver or demonstration.

– Promoting better care management for children and adults with asthma. About a quarter of all asthma-related health care spending is for hospital care, much of which could be avoided with better care management.(16) Successful models exist that involve nontraditional educators and patient self-management. A New York initiative focused on patient self-management and tailored case management reduced asthma-related emergency room visits by 78 percent.(17) A similar project in California reduced hospital admissions by 90 percent.(18)

– Initiatives to reduce hospital readmissions, which could improve care and lower costs. A recently published analysis shows that 16 percent of people with disabilities covered by Medicaid (excluding the dual eligibles) were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge. Half of those who were readmitted had not seen a doctor since discharge.(19) There is a significant body of evidence showing that improving care transitions as patients move across different health care settings can greatly reduce readmission rates. Interventions such as using a nurse discharge advocate to arrange follow-up appointments and conduct patient education or a clinical pharmacist to make follow-up calls has yielded dramatic reductions in readmission rates. One Colorado project, for example, reduced its 30-day readmission rate by 30 percent.(20) These practices can continue to be expanded in Medicaid, where the average cost of just one hospital admission for an individual with disabilities (excluding dual eligibles) is more than $5,700.(21)

– Implementing the new Health Homes option in the Affordable Care Act. This option offers new opportunities – and Federal support – to care for people with chronic conditions by providing eight quarters of 90 percent Federal match for care coordination services. Guidance to States has been issued (http://www.cms.gov/smdl/downloads/SMD10024.pdf), and HHS is establishing an intensive State-based peer-to-peer collaborative within the new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center to test and share information about different models. The option, which was effective January 1, 2011, could result in immediate savings, given the enhanced match, as well as a path for learning how to establish effective care coordination systems for people with chronic conditions.

– Promoting Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) that include Medicaid by bringing States into the planning and testing of ACO models that include, or even focus on, Medicaid plans and providers. CMS will work with States to ensure that States have ample opportunity to participate in these new models of care and benefit from any savings.

– Continuing to integrate health information technology. Health information technology (health IT) and electronic health information exchange are also key to driving down health care costs. Medicaid-financed incentive payments to eligible providers began in several States in January. HHS-funded health IT initiatives are underway in every State, providing implementation assistance and supporting improved care coordination. Additional Federal grants from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to support State-level initiatives will be awarded in February. (http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_gov__hitech_and_funding_opportunities/1310

2. Purchasing Drugs More Efficiently

Pharmacy costs account for eight percent of Medicaid program spending, with States spending $7 billion on prescription drugs in 2009.(22) While States have taken steps to reduce their pharmacy costs over the past decade, there is still strong evidence that many State Medicaid agencies are paying too high a price for drugs in the Medicaid program.(23) Recent court settlements have disclosed that the information most States rely upon to establish payment rates is seriously flawed. As a result, the major drug pricing compendium used by Medicaid State agencies will cease publication before the end of 2011, and States must find a new basis for drug pricing. We will work with States to help them manage their pharmacy costs and ensure their pharmacy pricing is fair and efficient:

– Provide States with a new, more accurate benchmark to base payments. A workgroup of State Medicaid directors and State Medicaid pharmacy directors has recommended a new approach to establishing a benchmark for rates, namely, use of actual average acquisition costs.(24) Alabama, the first State to adopt use of actual acquisition costs as the benchmark for drug reimbursement rates, expects to save six percent ($30 million) of its pharmacy cost in the first year of implementation. However, it is difficult and costly for each State to create its own data source for actual acquisition costs. States have recommended a national benchmark. In response, CMS is about to undertake a national survey of pharmacies to create a database of actual acquisition costs that States may use as a basis for determining State-specific rates. The data will be available to States later this year.

3. Dual Eligibles

There is great potential for improving care and lowering costs by ending the fragmented care that is now provided to “dual eligibles” – people who are enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare. While only 15 percent of enrollees in Medicaid and Medicare are dual eligibles, four out of every ten dollars spent in the Medicaid program and one quarter of Medicare spending are for services provided to dual eligibles.(25) Fragmented care, wasteful spending, and patient harm are significant risks with two programs serving some of the most frail and medically needy people, each with its own sets of rules and disparate financial mechanisms. Just a few examples can explain the problem and suggest some of the solutions:

– When Medicaid programs invest in health homes and similar initiatives that can help people who are dually eligible avoid hospitalizations, Medicare realizes most of the savings since it is the primary payer for the cost of hospital care for these people.

– If Medicare seeks to reduce hospital costs and avoid preventable hospital readmissions, extensive discharge planning relying on the availability of community-based long-term care may be required. Those long-term care services, however, are largely driven and financed by Medicaid, not Medicare.

Except in a very small number of specialized plans covering only about 120,000 of the 9.2 million dual eligibles, people do not have a team of caregivers that direct and manage their care across Medicaid and Medicare and States do not have access to information about the care delivered across the two programs.

The Affordable Care Act establishes a new Federal Coordinated Health Care Office to focus attention and resources on improving care for dual eligibles. The Office, which was formally announced on December 29, 2010, will work with States, physicians and others to develop new models of care. In the short term, the Office will focus on the following initiatives that will have an immediate impact on States’ ability to better manage care:

– Support State Demonstrations to Integrate Care for Dual Eligible Individuals. The Federal Coordinated Health Care Office recently announced that it will award contracts to up to 15 States of up to $1 million each to help them design a demonstration proposal to structure, implement, and evaluate a model aimed at improving the quality, coordination, and cost-effectiveness of care for dual eligible individuals. Through these initiatives, we will identify and validate delivery system models that can be rapidly tested and, upon successful demonstration, replicated in other States. Further investments from the new CMS Innovation Center are under review; this is a priority area for States and HHS. Additional areas of focus and opportunity are demonstrations to decrease transfers between nursing homes and hospitals and developing accountable care organizations to serve dual eligibles and other populations with complex health problems.

– Provide States with access to Medicare Parts A, B and D data. For several years State Medicaid agencies have been requesting access to Medicare data to support efforts to: 1) improve quality; 2) better coordinate care; and 3) reduce unnecessary spending for their dual eligible beneficiaries. CMS will make these data available to States in early 2011.

4. Improving Program Integrity

States and the Federal government share a common interest in ensuring that limited dollars are not wasted through fraud. According to the 2010 HHS Financial Agency Report, the three-year weighted average national error rate for Medicaid is 9.4 percent, meaning that $33.7 billion in combined federal and State funds was paid inappropriately. Our work on developing new ways to prevent fraud as well as some of the new tools created by the Affordable Care Act will bring additional options and resources to States to help them with their fraud prevention and detection efforts. No waiver or special demonstration is needed to move ahead on these initiatives.

– The Medicaid Integrity Institute provides free training to State Medicaid agency staff—it conducted 38 courses last year and trained 1,900 staff since February 2008. States participate as faculty, receive training, and help shape the curriculum. We are planning a special series of web-based trainings for State Medicaid agencies to share best practices and inform States about new provisions of the law aimed at preventing fraud.

– The Affordable Care Act requires the screening of providers and provides States with new authority to help keep problematic providers from enrolling in Medicaid. The vast majority of Medicaid providers and suppliers participate in both Medicaid and Medicare, so Medicare provider screening actions in Medicare will also benefit Medicaid and CHIP programs. A significant value for States is expected. CMS will provide active support and assistance to States, including training of State Medicaid and CHIP program staff and best practice guidelines.

– New, cutting edge initiatives are being developed to prevent fraud in the Medicare program and will be shared with States to ensure that Medicaid gets the full benefit of Medicare advances in this area including analytics such as predictive modeling to identify patterns and examine high-cost problem areas across all types of care.

– CMS will be organizing new Payment Accuracy Improvement Groups with States grouped based on their shared interest in particular program integrity vulnerabilities. States with similar interests will work with CMS, as well as Federal contractors and other experts, to target issues and problem.

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by USA Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

** More information at USA Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

(1) 2010 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid. Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (for enrollment data). National Health Expenditure Projections 2009-2019. Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (for expenditure data).

(2) Kaiser Family Foundation 2010.

(3) Kaiser Family Foundation 2010.

(4) 2010 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid. Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

(5) CMS analysis of FY 2008-2010 Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System (MBES) data.

(6) Martin A. et al, “Recession Contributes To Slowest Annual Rate Of Increase In Health Spending In Five Decades,” Health Affairs, 30(1): 11-22, January 2011.

(7 Section 1115 of the Social Security Act authorizes the Secretary of HHS to waive compliance with certain specified provisions of the law or to permit expenditures not otherwise allowed under the law in the context of an “experimental, pilot of demonstration project” that the Secretary determines is “likely to assist in promoting the objectives” of the program.

(8) CMS Analysis of Inpatient Hospital Spending for Blind/Disabled Non-Dual Medicaid Beneficiaries, FY2008, MSIS (Medicaid Statistical Information System), FFS only. Inpatient claim count is used as a proxy for inpatient admission count.

(9) ASPE Analysis of the Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) data for 2008. Spending for mandatory and optional populations.

(10) CMS analysis of FY 2008 CMS MSIS data.

(11) CMS analysis of FY 2008 CMS MSIS data.

(12) November 2010 presentation by the National Association of Children’s Hospitals.

(13) Tita, A., et.al. The New England Journal of Medicine. January 8, 2009 volume 360, No. 2, pages 11-120.

(14) Eunju Lee, et al. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2009; 36(2):154–160).

(15) The Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative Writing Committee. A statewide initiative to reduce inappropriate scheduled births at 360/7–386/7 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:243.e1-8.

(16) American Lung Association. Trends in Asthma Morbidity and Mortality, January 2009.

(17) Hoppin, et al, August 2010. Asthma Regional Council.

(18) Hoppin, et al, August 2010. Asthma Regional Council.

(19) Hospital Readmissions among Medicaid beneficiaries with Disabilities: Identifying Targets of Opportunity. Center for Health Care Strategies, December 2010.

(20) Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep25;166(17):1822-8.

(21) CMS Analysis of Inpatient Hospital Spending for Blind/Disabled Non-Dual Medicaid Beneficiaries, FY2008, MSIS (Medicaid Statistical Information System), FFS only. Inpatient claim count is used as a proxy for inpatient admission count.

(22) National health expenditures, historical tables. Includes state and local spending on Medicaid prescription drugs for 2009. https://www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/02_NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.asp.

(23) See for example, OEI-05-05-00240, Medicaid Drug Price Comparisons: Average Manufacturer Price to Published Prices, June 2005.

(24) Post AWP Pharmacy Pricing and Reimbursement: Executive Summary and White Paper. American Medicaid Pharmacy Association and the National of Medicaid Directors, June 2010. Accessed at: http://www.nasmd.org/home/doc/SummaryofWhitePaper.pdf

(25) Kaiser Family Foundation. Dual Eligibles: Medicaid Enrollment and Spending for Medicare Beneficiaries in 2007, December 2010. Accessed at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7846-02.pdf

– The Affordable Care Act requires the screening of providers and provides States with new authority to help keep problematic providers from enrolling in Medicaid. The vast majority of Medicaid providers and suppliers participate in both Medicaid and Medicare, so Medicare provider screening actions in Medicare will also benefit Medicaid and CHIP programs. A significant value for States is expected. CMS will provide active support and assistance to States, including training of State Medicaid and CHIP program staff and best practice guidelines.

– New, cutting edge initiatives are being developed to prevent fraud in the Medicare program and will be shared with States to ensure that Medicaid gets the full benefit of Medicare advances in this area including analytics such as predictive modeling to identify patterns and examine high-cost problem areas across all types of care.

– CMS will be organizing new Payment Accuracy Improvement Groups with States grouped based on their shared interest in particular program integrity vulnerabilities. States with similar interests will work with CMS, as well as Federal contractors and other experts, to target issues and problem