Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). History of the School.

Sections for Harvard University

- About Harvard University.

- About Harvard University. Information.

- Harvard Medical School. Fact & Figures.

- Harvard Medical School. Generations of Leaders.

- Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH).

- Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). History of the School.

- The Forum at Harvard School of Public Health

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). History of the School.

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). Introduction to the School

Since 1922, the Harvard School of Public Health has led the world in public health research and education. It has guided an ever-expanding field and embodied the highest standards of scientific rigor and social commitment. Its landmark discoveries and world-class graduates have saved lives and lifted the burden of disease around the globe.

Harvard School of Public Health, 1937

Harvard School of Public Health, 1937

The School traces its roots to public health activism at the turn of the last century, a time of energetic social reform. HSPH is the direct descendant of the first professional training program of public health in America, a joint venture forged in 1913 between Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and known as the Harvard-MIT School for Health Officers. The partnership offered courses in preventive medicine at Harvard Medical School, sanitary engineering at Harvard University and allied subjects at MIT.

In 1922, the School split off from MIT, helped by a sizeable grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. From the start, faculty were expected to commit themselves to research as well as teaching. In 1946, no longer affiliated with the medical school, HSPH became an independent, degree-granting body.

Many of the changes that unfolded in public health over the 20th century trace their origins to HSPH. Initially, researchers were preoccupied by deadly epidemic infections and by the scourges of unfettered industrialization. During the School’s first 50 years, the public health enterprise matured, drawing on a full range of analytic, scientific and policy disciplines. Today, the School’s purview extends from the gene to the globe. It work encompasses not only the basic public health disciplines of biostatistics and epidemiology, environmental and occupational health, but also molecular biology, , quantitative social sciences, policy and management, human rights, and health communications. Its leadership and outreach have informed public health practice around the world ? from decades of research in the People’s Republic of China to studies of health system reform in Taiwan and Poland, from collaborations on environmental health in Cyprus to intensive field training in Latin America.

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). History of the HSPH Shield

HSPH Shield

The Harvard School of Public Health shield is based on the family arms of Dr. Henry P. Walcott (1838-1932), a Cambridge physician and acting president of the University. Walcott was a public health luminary, having served for 28 years as chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Health, and as president of the American Public Health Association. Walcott advanced the knowledge and apqplication of the principles of bacteriology, sanitary science and medicine to a degree that made Massachusetts one of the world leaders in these domains.

The Walcott arms feature a white shield with a black cross whose arms end in three semicircles, or trefoils. At the end of each arm and in the center are yellow fleur-de-lis.

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). Research Topics.

Halting Epidemics.

Through all of history, outbreaks of infectious disease have ravaged human societies, spreading chaos and fear. Building on the 19th-century germ theory of disease, the School in its formative years made key discoveries about yellow fever, river blindness, diphtheria, measles, sleeping sickness, and other infections.

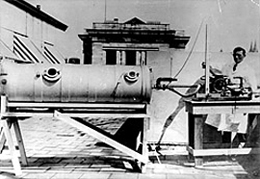

The iron lung, a device that saved thousands afflicted with polio until a vaccine was found, was invented at HSPH.

But it was polio that was the single most emotional topic in biomedical research. In 1934, School faculty invented the Drinker respirator later dubbed the “iron lung” which enabled polio victims, afflicted by respiratory paralysis, to breathe. Until the 1940s, research on a polio vaccine had stalled because scientists could not grow the virus in a form that would permit mass production of a vaccine. In 1947, HSPH succeeded for the first time in growing the virus in non-nervous system tissue a monumental breakthrough that led to the development of a protective vaccine and a Nobel Prize for faculty member Thomas Weller.

School scientists have also deciphered the secrets of other infectious diseases. In the late 1970s, they identified a recently discovered tick species as the vector of Lyme disease, then a newly-emerging infection. In the early 1990s, with a new wave of globally emerging infections on the rise, the HSPH Working Group on New and Resurgent Diseases showed that the alarming new infections had sprung from changes in the environment, either natural or caused by humans.

In 2006, Richard Cash received the Prince Mahidol Award for “exemplary contributions in the field of public health.” Cash was credited with saving millions of lives worldwide by promoting the use of oral rehydration therapy to treat cholera and other diarrheal diseases.

Confronting AIDS.

In June 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control issued a report with a deceptively bland title: “Pneumocystis Pneumonia Los Angeles” It summarized the first reported cases of the fatal pandemic later named AIDS. When the long-simmering infection surfaced, HSPH helped lead a grueling counter-assault. Its laboratory discoveries have pointed the direction for ongoing research into vaccines and treatments. Its epidemiologic modeling and data analysis helped describe the contours of the epidemic and the best interventions. Its public policy and human rights commitments have set standards worldwide.

Prof. Max Essex and Dr. Joseph Makhema in Jwaneng, Botswana,

site of an HV vaccine trial conducted

by the Botswana-Harvard Partnership. / Photo credit: Richard Feldman

As early as 1975, the School generated the first strong evidence that a lethal suppression of the immune system could be caused by an infectious agent a discovery that was later central in the unraveling of AIDS. School researchers led by Max Essex were the first to suggest that the causative agent was a retrovirus. They also determined that the virus could spread through transfused blood, and identified which antigens were most useful for blood-bank screening. And School scientists proved that HIV could be transmitted through heterosexual intercourse.

By the mid-1980s, HSPH investigators identified two glycoproteins on the HIV-1 surface that enabled the virus to infect cells and became targets for vaccine development. They uncovered evidence of a second AIDS virus, HIV-2. In 1990, HSPH showed that the drug AZT was safe and effective for HIV-infected adults who had no symptoms of AIDS but low levels of CD4 immune system cells. Later, an HSPH study found that giving the drug to HIV-positive pregnant women dramatically reduced HIV transmission from mother to fetus.

In the early 1980s, the School established a presence in Africa to meet the challenges posed by the pandemic. In 1996, it launched the Botswana HSPH AIDS Initiative Partnership, a research and training program that was the largest of its kind in Africa at the time, as well as the first dedicated HIV research lab in southern Africa. In 2004, based on its longstanding commitment to confront HIV/AIDS on the continent, the School was awarded one of four President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) grants. By 2009, the overall PEPFAR effort was credited with saving approximately one million lives in Africa.

_________________________________________________

Environmental Poisons.

School researchers have long focused on threats to health, including hazardous substances found in air, water and the workplace. Their investigations have helped set global standards for protection against environmental contaminants.

When HSPH was founded, factories and industrial trades were literally poisoning workers, and occupational health had emerged as an urgent concern. From its earliest days, HSPH has also helped define the field of industrial hygiene.

The Harvard Six Cities Study established a scientific foundation for amendments to the Clean Air Act and other EPA regulations./ (c) iStockphoto.com/Thad

Beginning in the 1920s, the School developed effective methods for resuscitating victims of illuminated gas poisoning and electric shock. HSPH faculty investigated mercury poisoning in the felt hat industry, and in 1925 took a prescient stance against newly-introduced leaded gasoline. The School developed methods for deterring the adverse health effects of dust concentrations in mines, factories and quarries.

The School also gained national prominence for investigating radium poisoning among workers who painted luminous watch and clock dials. Decades later, HSPH scientists investigated the effects of radioactive fallout from Cold War weapons testing leading to the establishment of maximum permissible standards for all workers exposed to radiation.

In the 1950s, the School helped establish the connection between environmental exposure to airborne pollutants and subsequent increases in asthma, lung cancer, chronic respiratory disease, and overall death rates. Many of these findings served as scientific underpinnings for regulations enacted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The Six Cities Study began in 1974, in response to an energy crisis during which the nation was burning more high-sulfur coal. One of the most influential, innovative and longest-running investigations of the effects of air pollution on human health, it established a scientific foundation for amendments to the Clean Air Act and other EPA regulations. Scientists discovered that deaths from lung cancer, lung disease and heart disease were significantly higher in the most polluted of the cities examined. The study also revealed a lethal connection between small particulate matter and cardiovascular deaths. Perhaps most important, it proved that indoor air quality posed a bigger threat to overall health than did outdoor air.

Today, at the cutting edge of molecular epidemiology, School scientists are using DNA in blood samples from Shanghai textile workers to explore links between airway disease, airborne toxins and genetic factors, and are developing biologic markers for pollution-induced diseases.

Child and Maternal Health.

Inspired by the idea that true preventive medicine begins with the child, HSPH in 1922 introduced the first teaching program in the nation devoted to promoting health in the well child. A decade later, the landmark Longitudinal Growth Study tracked more than 300 individuals from prenatal stages into adulthood. The first comprehensive study of normal childhood growth and development, it provided the basis for reference growth charts, enabling doctors and parents to easily spot malnutrition.

HSPH Professor Jack Shonkoff is drawing attention to the importance of early childhood years to future health and economic productivity. /Photo Credit: Kent Dayton

By the 1940s, HSPH was charting the future of maternal and child health, with research into newborn care, the connections between maternal and fetal health, complications of pregnancy, neonatal deaths, breast- vs. formula-feeding, care of the unmarried mother, problems of adoption, and other issues. Today, School epidemiologists are carrying on the tradition, connecting birth outcomes to later disease risk in adulthood in the U.S. and abroad.

Lifestyle and Health.

Starting in the mid-20th century, the primary causes of death worldwide shifted from infections to chronic conditions, such as heart disease and cancer. HSPH has meticulously documented this change, standing at the forefront of both basic and applied research. Its discoveries in nutrition, exercise and other individual risk factors have reconfigured the public health landscape.

HSPH has developed a healthy eating pyramid based on the latest research.

HSPH has developed a healthy eating pyramid based on the latest research.

The Nurses’ Health Study I a collaboration begun in 1976 among School scientists and researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Channing Laboratory was the first of a series of prospective cohort investigations, now among the largest and oldest in the world. The study , produced a lengthy list of surprising findings. Among these: that a high-fat diet increases colon cancer risk but not breast cancer risk; that weight gain after adolescence raises death rates in midlife; and that light smoking more than doubles the risk of heart disease. The Physicians’ Health Study showed that an aspirin a day reduces the risk of heart attack.

The School’s Department of Nutrition, founded in 1942, was the first such department in a medical or public health school in the world. Its groundbreaking research includes work on the health benefits and hazards of proteins and fats; the components of a well-balanced diet; and clinical aspects of obesity. HSPH scientists created the first animal model for hypercholesterolemia, and demonstrated the protective nature of HDL cholesterol and the blood vessel-damaging potential of LDL cholesterol.

In the 1970s, HSPH scientists helped map the government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans; decades later, they proposed an alternative Healthy Eating Pyramid based on the Mediterranean diet and including recommendations for daily exercise and weight control. In 2006, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration ordered that nutrition labels for packaged foods list all harmful trans fatty acids, it signified a victory for HSPH scientists led by Walter Willett. A vigorous public health advocate, Willett not only amassed evidence that these solid fats raise the risk of coronary artery disease, Type 2 diabetes and other ills, but also waged a campaign to label and ultimately eliminate the ingredient from manufactured food products and restaurant meals.

Established in 1988, the Center for Health Communication has used entertainment media and mass communication to shift social norms in healthier directions. Among its innovations, it worked with Hollywood to incorporate the Swedish-originated designated driver concept into entertainment programming, which decreased alcohol-related traffic crashes. So successful were the School’s efforts, the Random House Webster’s College Dictionary (1991 edition) added “designated driver” to the American lexicon.

In a similar vein, HSPH faculty have led the charge for worldwide tobacco control, providing the scientific expertise to convince nations in Europe and Asia to pass smoking bans for public places. In a pair of 2008 studies, HSPH investigators revealed a deliberate strategy among tobacco companies to recruit and addict young smokers by manipulating menthol content, and by heavily advertising in places that cater to youth.

In 2008, HSPH researchers published the largest and longest-running study to estimate the impact of a combination of lifestyle factors on mortality. The study concluded that not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, regular physical activity, and a nutritious diet dramatically lowered the risk of dying from all causes during the 24 years of the study. In 2009, resolving a long-simmering scientific and popular debate, HSPH investigators found that diets that reduced calories led to weight loss regardless of the proportion of carbohydrates, protein or fat.

Genetics of Disease.

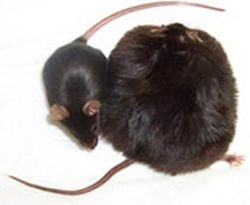

Shifting their view from the macro to the micro, HSPH scientists are exploring genetic underpinnings of chronic disease. School researchers have made major discoveries about the obesity-related condition known as “metabolic syndrome.” In 2007, a team created a designer compound that protects mice from those conditions and other problems a stepping-stone to clinical trials in humans. Researchers have identified in mice a newly-discovered class of hormones that helps stop or even reverse obesity-related conditions such as insulin resistance. They have also engineered transgenic mice resistant to atherosclerosis, providing insights into prevention and treatment.

A normal mouse and its obese cousin.

The School has developed a breakthrough statistical method and computer package known as the Family-Based Association Test (FBAT), which has led to the identification of a gene mutation strongly tied to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. And HSPH scientists have discovered inherited gene variants that raise the risk of breast cancer in women a finding considered the most important discovery in breast cancer genetics since the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were identified in the 1990s.

More recently, faculty have unveiled a detailed genetic map of the malaria parasite, and the first genome sequence of an extensively drug-resistant strain of the TB acterium discoveries that may accelerate the quest for treatments.

Vital Statistics.

Traditionally, public health measures the distribution of a problem, defines the causes, and designs and implements interventions. Every step of this process relies on reliable numbers generated by epidemiology: the study of factors affecting the health and illness of populations. Since its founding, HSPH has made a priority of teaching and research into the methods of epidemiology, analyzed data on epidemic and endemic disease, and evaluated control methods.

Faculty Nan Laird and Christoph Lange invent new statistical tools for gene analysis./Photo Credit: Kent Dayton

When infectious causes of death and disease gave way to chronic conditions, HSPH built the premier chronic disease epidemiology department in the nation. It introduced the idea of the “web of causation,” a model in which each component generates myriad effects. The School’s groundbreaking research uncovered the link between breast cancer risk and reproductive experience. In 1981, HSPH epidemiologists Dimitrios Trichopoulos and Brian MacMahon were the first to demonstrate the health threat from exposure to second-hand cigarette smoke. And the School’s 1996 “Global Burden of Disease” report was the first attempt to develop a comprehensive set of estimates for patterns of mortality and disability for 107 chronic and infectious diseases, from AIDS to heart disease to depression.

The School has also made signal contributions to the field of biostatistics the theory and application of statistical science to public health problems and biomedical research. HSPH provided the biostatistical design for the first study showing a connection between DES a drug used to prevent miscarriages and vaginal cancers, miscarriages and infertility in a mother’s female offspring. Beginning in the 1980s, HSPH built large biostatistics laboratories capable of administering and keeping tabs on hundreds of clinical trials at once. The labs played a key role in the development of cancer treatments. And the Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, established in 1995, became the nation’s leading facility for assessing antiviral therapies for HIV infection, analyzing treatments for common opportunistic infections, and bringing innovations to the design and coordination of AIDS clinical trials.

Today, HSPH is investing in its Bioinformatics Core and Program on Quantitative Genomics to pave the way for more effective prevention and intervention. The School’s infectious disease epidemiologists have been intimately involved in identifying and tracking global emerging infections of the 21st century. As the new millennium unfolds, they have made crucial discoveries in the genetics of extensively drug-resistant TB, in the transmission patterns of SARS, and in the spread and virulence of the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus.

HSPH scientists have also developed improved treatment protocols to reduce hospital selection for drug-resistant bacteria. Its biostatisticians have discovered out how to analyze massive quantities of genetic data, speeding the quest for the genetic basis of asthma, diabetes and other disorders.

Society and Health.

What we term “health disparities” the consistent gap in physical and mental well-being between the most privileged members of society and the most socially and economically disadvantaged catalyzed the modern public health movement in the nineteenth century. Over the past two decades, HSPH has led a new wave of studies on the health effects of poverty, racism, social class, gender, and political economy.

In 1994, HSPH faculty launched the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, a large prospective study of high-risk children that applied the rigors of epidemiological research to the multifactorial problems of violence and antisocial behavior. Scholars have investigated the causes and effects of teen violence, and have developed national interventions.

In a long-term study of mortality patterns in the U.S., School scientists showed that while overall life expectancy increased between 1960 and 2000, it declined or stagnated among a significant segment of the population in the Deep South, along the Mississippi River and in Appalachia a finding reaffirmed in a 2008 HSPH study. Creating a novel geocoding tool, HSPH faculty have demonstrated that people who live in neighborhoods with the highest poverty levels suffer more heart disease, cancer, diabetes, sexually transmitted diseases, low birth weight infants, and homicides. School researchers have also uncovered disturbing patterns of inequities in hospital care for minority and low-income populations.

Governments around the world have long applied the School’s expertise to health problems rooted in social conditions. In the 1980s, economist David Bell worked on pressing problems in health, population and economic growth in developing nations. In the 1990s, physician Lincoln Chen united health and population studies with development research, and initiated the original Global Burden of Disease Study. More recently, a team of HSPH economists, demographers and global health experts have found that improvements in health are major factors propelling economic success in China and India a concept known as “health-led growth.” The findings have motivated governments to address health disparities as a spur to the economy.

Health Systems.

From its inception as the world’s first School for Health Officers, HSPH has dedicated itself to bridging the latest scientific knowledge and frontline practice.

Since the 1970s, the School has pioneered studies delving into the cost-effectiveness of medical interventions. The 1979 New England Journal of Medicine article “Evaluation of Medical Practices: The Case for Technology Assessment,” (abstract) by Deans Fineberg and Hiatt, helped forge the field of medical technology assessment. Other HSPH papers and books laid the groundwork for evidence-based medicine and health decision science.

Four young girls pose with Sue Goldie, a MacArthur “genius” award winner, in Haiti.

In 1988, an HSPH team was asked by Medicare officials to devise an alternative reimbursement scheme for doctors, putting physician payment on a rational basis and emphasizing primary and preventive care. A few years later, the Harvard Medical Practice Study (abstract), the first comprehensive measure of medical injuries and preventable medical errors in hospitals, propelled the modern patient safety movement with the Institute of Medicine reports “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System” (1999) and “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century” (2001).

In 2008, School researchers, led by Atul Gawande, joined with the World Health Organization in a Safe Surgery initiative, introducing new safety checklists for surgical teams to use around the world as a simple and effective way to reduce millions of deaths and injuries from medical errors during major surgery.

HSPH has also taken its health systems expertise abroad. In 2006, the School helped create the Public Health Foundation of India, a public/private partnership dedicated to education, policy and practice. In 2005, Sue Goldie received a MacArthur “genius” award for creatively applying the tools of decision science to combat major public health problems. In recent years, Goldie has concentrated her efforts on identifying effective and cost-effective strategies to reduce the burden of cervical cancer, the most common cause of cancer death in women worldwide.

Human Rights.

HSPH has helped broaden the definition of health law to embrace some of the most hotly debated issues of the late 20th century–abortion rights, human subjects research, the legal definition of death, and AIDS discrimination.

First prize winner in 2008 HSPH Student Photo Contest: “A Light,” (Maputo, Mozambique) by Oriana Maria Ramirez Rubio

The School is renowned for its commitment to human rights. Inscribed on the outside wall of The François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights, in the six official languages of the World Health Organization (WHO), is a statement from the WHO constitution: “The highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being.” The motto, adorning the world’s first academic center to focus exclusively on the practical dynamic between the issues of health and human rights, captures the School’s singular dedication to human rights. Since the Center’s founding in 1993, it has become an academic focal point for a broad-based movement uniting public health and human rights.

In 1994, the FXB Center sponsored the First International Conference on Health and Human Rights. But the School’s dedication to human rights reaches further back. HSPH researchers studying the War in Bosnia in the 1990s and the disintegration of the former Yugoslavian republic concluded that the conflict constituted a “war on public health,” with key indicators of population health declining.

In 1960, HSPH’s Bernard Lown (inventor of the direct-current cardiac defibrillator) co-founded Physicians for Social Responsibility. In 1981, Lown went on to co-found the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. The organization received the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize.

_________________________________________________

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). The Deans.

Under Dean Edsall, HSPH emerged as a leading research and training center in the fields of sanitary engineering, tropical medicine and industrial medicine. HSPH scientists amplified the power of serums and vaccines; conducted important studies in poliomyelitis, sleeping sickness, and hookworm; and studied the special needs of premature infants and of individuals afflicted with mental illness. Edsall was an early and strong proponent of medical education reform.

Cecil Drinker: 1935-1942

An eminent physiologist and the School’s first full-time dean, Dean Drinker initiated groundbreaking studies in industrial medicine, bacteriology and child development. The School dramatically expanded enrollment and, for the first time, admitted women as candidates for degrees. Drinker’s younger brother, Philip Drinker, invented the first widely used iron lung.

Edward G. Huber: Acting Dean, 1942-1946

Acting Dean Huber steered HSPH through the extreme shortages of money and personnel during World War II, and paved the way for an institution that was fully autonomous from Harvard Medical School.

James Stevens Simmons: 1946-1954

An HSPH graduate–as well as a physician, soldier and scientist–Dean Simmons pushed for an expanded national commitment to train public health professionals. He called upon the nation’s schools of medicine to place increased emphasis on preventive medicine. Before joining HSPH, Simmons had studied malaria, dengue and other tropical scourges, and developed a preventive medicine program that safeguarded the health of men in the military during World War II.

John C. Snyder: 1954-1971

A bacteriologist, Dean Snyder had come to HSPH to study rickettsial diseases, international health and population control. He established the Department of Demography and Human Ecology–the first such department in any school of public health. He also created a University-wide center for population studies and a department of behavioral sciences. Snyder left a legacy of new facilities, academic centers, faculty expansion, and educational excellence that imprinted the School with much of its present-day character.

Howard H. Hiatt: 1972-1984

A Harvard-trained physician and former physician-in-chief at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Hospital, Dean Hiatt defined health and health care in the broadest possible terms. During his tenure, he strengthened and broadened work in quantitative analytic sciences, introduced molecular and cell biology into the School’s research and teaching, and created its program in health policy and management–the first in a public health school. Hiatt is currently Assistant Chief of the Division of Global Health Equity at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and interim director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) Center for Health and Human Rights at HSPH.

Harvey V. Fineberg: 1984-1997

A visionary and eloquent public health advocate, Dean Fineberg launched interdisciplinary centers and programs, including the Harvard AIDS Initiative, the Harvard Center for Cancer Prevention, the Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, and the Harvard Center for Children’s Health. He strongly promoted a health and human rights agenda, molecular epidemiology, health communications, and research in public health practice. Fineberg currently serves as president of the Institute of Medicine.

James H. Ware: 1997-1998

Longtime Academic Dean James H. Ware, a biostatistician, became Acting Dean in 1997 as Fineberg assumed the position of Provost of Harvard University. During his tenure as academic dean (1990-2009), the student body doubled in size and the research budget grew at an annual rate of eight percent.

Barry R. Bloom: 1999-2008

Under Dean Bloom, a distinguished immunologist and global health authority, the School responded to rapid advances in technology and to deepening health crises. HSPH adopted an interdisciplinary emphasis on genes and the environment, quantitative social sciences and bioinformatics, and global health. Bloom reinvigorated the HSPH educational mission and initiated a long-term planning matrix. By the end of Bloom’s tenure, the School was annually accepting more than 1,000 students from over 50 different countries, and the number of faculty and researchers topped more than 400. During his tenure and continuing today, Bloom has kept up an active career in bench science, as the principal investigator of a laboratory researching new vaccine strategies for tuberculosis.

Julio Frenk: 2009-present

Dean Frenk assumed his post on January 1, 2009. He is the T & G Angelopoulos Professor of Public Health and International Development, a joint position in the faculties of the Kennedy School and HSPH. He was founding Director General of the National Institute of Public Health in Mexico (1987-1992) and Executive Vice President and Director of the Center for Health and the Economy at the Mexican Health Foundation (1995-1998). From 1998 to 2000, he served as Executive Director of Evidence and Information for Policy at the World Health Organization. As Minister of Health of Mexico from 2000 to 2006, Frenk pursued an ambitious agenda to reform the nation’s health system, with an emphasis on redressing social inequality and establishing a program of comprehensive national health insurance that extends healthcare to 50 million. After completing his term, Frenk served as a senior fellow in the global health program of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Dean Frenk has stated that he intends to build upon the HSPH heritage as a steward of health by engaging globally with five current revolutions: in the life sciences, in telecommunications, in systems thinking, in knowledge management, and in human rights.

_________________________________________________

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). Leaders and Prizewinners.

CDC/WHO Connections

HSPH graduates have gone on to illustrious careers around the world. Among the School’s most high-profile graduates are six Directors of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: James Lee Goddard, (M.P.H. ’55, CDC Director,1961-1966); David J. Sencer (M.P.H. ’58, 1966-1977); William H. Foege (M.P.H. ’65, 1977-1983); James O. Mason (M.P.H. ’63, D.P.H. ’67, 1983-1985); Donald R. Hopkins (M.P.H. ’70, CDC Acting Director 1985-1989); and Jeffrey Koplan (M.P.H. ’78, 1998-2002).

HSPH graduates have also assumed leadership positions at the World Health Organization. Gro Harlem Brundtland (M.P.H. ’65) was WHO Director-General from 1998 to 2003. William Foege, Donald Hopkins and Ralph Henderson (M.P.H. ’70) played prominent roles in the WHO’s global smallpox eradication campaign. In 1986, Jonathan Mann (M.P.H ’80) founded the WHO’s Global Program on AIDS.

HSPH MacArthur “Genius” Grant Recipients

- 2006: Atul Gawande, Associate Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management

- 2005: Sue Goldie, Roger Irving Lee Professor of Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management

- 2003: Jim Yong Kim, former director of the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights

- 1991: Joel Schwartz, Professor of Environmental Epidemiology, Department of Environmental Health

- 1981: John Cairns, Professor of Microbiology emeritus

Nobel Prize Winners

Two HSPH-affiliated scientists have been awarded the Nobel Prize. In 1954, Thomas Weller shared the Prize in Physiology and Medicine for devising a way of growing polio viruses in tissue culture. The International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, co-founded by faculty member Bernard Lown, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985. Amartya Sen, from the School’s Department of Population and International Health, won the 1998 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his work on human rights, poverty and famine.

_________________________________________________

Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). Facts and Figures.

Below is a sampling of the School’s accomplishments:

- Launched the “Designated Driver” campaign in the U.S. to curb alcohol-related traffic crashes, which contributed to a drop in fatalities of more than 25 percent.

- Discovered a second human immunodeficiency virus, HIV-2, which causes most HIV infections in West Africa. Also demonstrated that HIV-2 is less virulent and less infectious than HIV-1, and that HIV-2 seems to offer some protection against HIV-1. Because the genetic structures of the viruses are similar, this work may provide clues to understanding the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and hasten vaccine development.

- Determined that a retrovirus was the agent causing AIDS, that the HIV virus could be transmitted through blood and blood products given through blood transfusions, and identified which viral antigens were most useful for blood-bank screening.

- Provided, through the Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, the services needed to guarantee the statistical integrity and quality of most government AIDS trials in the U.S. since 1995.

- Provided the first evidence that HIV could be transmitted through heterosexual intercourse.

- Identified a protein on the surface of HIV that provides the basis for accurate epidemiologic monitoring, a novel approach to drug development, and diagnostics. This protein is the most likely target for a vaccine.

- Prompted revolutionary revisions to the U.S. Clean Air Act through the Six Cities Study, begun in 1974 in response to the U.S. energy crisis. The study found that air pollution-related cardiopulmonary problems were occurring at exposure levels below existing standards; the most dangerous components of air pollution were microscopic bits of solid matter (particulates) produced by fossil fuel combustion; indoor air pollution was sometimes significantly riskier than outdoor pollution; and that passive smoking has significant effects on the respiratory health of children.

- Demonstrated that not all fats are “bad fats,” but that different types have different effects—with trans fatty acids being harmful and plant oils being beneficial—revolutionizing how the U.S. government and health experts worldwide give nutritional advice. *

- Showed that the large majority of coronary heart disease and diabetes cases can be prevented by avoidance of smoking, moderate physical activity, weight control, a diet emphasizing healthy fats, healthy carbohydrates, and generous intake of fruits and vegetables, and optional moderate alcohol intake. *

- Released a report showing that more than half of U.S. cancer deaths result from modifiable lifestyle habits, including smoking, poor diet, obesity, and lack of exercise. This summary of cancer’s preventable causes led to the development of the website Your Cancer Risk (now Your Disease Risk), which provides personalized recommendations for risk reduction.

- Determined that an aspirin a day protects men and women from heart attacks. *

- Launched the “patient safety movement” with the Harvard Medical Practice Study, the first comprehensive measure of medical injuries and preventable medical errors in hospitals. The study provided critical data for the internationally renowned Institute of Medicine report, “To Err is Human.”

- Discovered how to grow poliovirus in non-nerve tissue, a discovery for which Thomas Weller won a 1954 Nobel Prize and which paved the way for the development of polio vaccines in the mid-1950s.

- Invented the iron lung, a device that saved thousands afflicted with polio until a vaccine was found.

- Invented the direct-current cardiac defibrillator, which has saved thousands of people suffering from erratic heart rhythms or cardiac arrest.

- Helped public health officials plan effective strategies for containing the SARS epidemic by devising a mathematical model to estimate the virus’s potential to spread.

- Conducted seminal studies of patients with kidney and heart disease showing that even after coming to medical attention, minorities and the poor receive lower rates of surgery (when appropriate) and lower quality care than whites and those of higher socioeconomic status.

- Identified the “demographic dividend” that occurs in developing countries as health improvements and falling infant mortality lead to a decline in fertility and a baby boom generation that dominates the age structure. If appropriate policies are in place, the surge in labor supply and savings produced by this baby boom generation as it matures can fuel a remarkable economic growth spurt—suggesting that “health makes wealth.”

- Determined that deer ticks transmit the agent that causes Lyme disease, described the life cycle of this tick, and defined the role of deer and of mice in the transmission of this pathogen.

- Engineered transgenic mice resistant to atherosclerosis, providing insights on prevention and treatment of the disease.

- Collaborated with the World Health Organization and the World Bank to release the landmark Global Burden of Disease report, which documents the world’s leading causes of death and disability and analyzes the impact of 107 major diseases and health hazards in nine different global regions.

- Published a groundbreaking study highlighting the hazards of passive smoking, or “second-hand smoke.” The study linked this exposure to lung cancer.

- Identified new, lower cost, and more efficient ways to screen for and prevent cervical cancer in developing countries, where it is a leading cause of cancer deaths in women.

- Provided the biostatistical design for the first study showing a connection between DES, a drug used to prevent miscarriages, and vaginal cancers, miscarriages, and infertility in a mother’s female offspring. Male DES babies had significantly higher rates of structural abnormalities and fertility problems, while the mothers were 50 percent more likely to develop breast cancer.

- Created the Resource-Based Value Scale (RBRVS) by calculating the time and intensity of effort required for every medical procedure, replacing the traditional charge-based fee-for-service payment by Medicare. By 1995, most public and private insurance programs in the U.S. had adopted the RBRVS model for paying physician services. By 2004, Australia, Canada, France, and private insurance plans in Britain adopted the RBRVS.

- Showed that alterations in surface tension in the smallest air sacs in the lungs were the fundamental cause of Respiratory Distress Syndrome in newborns. The discovery led to improved clinical care of babies with breathing problems, including replacing missing lung surfactant.

- Developed statistical methods that led to the identification of a new gene mutation strongly linked with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The protein coded for by this gene—known as alpha-2 macroglobulin (A2M)—interacts with proteins coded by other suspected Alzheimer’s genes, suggesting a process that could be key to the disease’s development.

- Began pioneering studies of the cost-effectiveness of medical interventions, launching the discipline now known as health decision science. Such studies, which introduced the concept of expressing cost in relation to quality-adjusted life-years saved, or QALYs, are used to guide health care policy throughout the world.

- Diagnosed the causes of and helped establish controls against radium poisoning in the watch maker industry, mercury poisoning in the felt-hat industry, and carbon monoxide poisoning in garages, printing establishments, tunnels, and the mining industry.

- Worked collaboratively with labor and management to improve worker safety in the rubber-tire, meat-packing, and automobile industries.

- Studied the health impact of the presence of heavy metals, such as lead, arsenic, and manganese, in environments around the world and devised low-cost alternative methods for counteracting their effects.

- Documented that life expectancy is worsening or stagnating for a large segment of the U.S. population.

Additional Facts

- Gro Harlem Brundtland, MPH ’65, was Director-General of the World Health Organization from 1998-2003.

- In the 1920s, thanks to HSPH faculty member Alice Hamilton’s pioneering examination of worker poisoning in the lead industry, Illinois became the first state to adopt legislation safeguarding workers’ health. Hamilton was also Harvard’s first female professor.

- Two HSPH-affiliated scientists have been awarded the Nobel Prize. In 1954 Thomas Weller received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. Amartya Sen won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1998. Another faculty member, Bernard Lown, co-founded the Nobel Prize-winning group Physicians for Social Responsibility.

- Since 1962, six directors of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have been Harvard School of Public Health graduates.

_________________________________________________

###

* The above information is adapted from materials provided by Harvard University

_________________________________________________________________