About The Johns Hopkins University. History.

Sections for Johns Hopkins University

- About The Johns Hopkins University.

- About The Johns Hopkins University. History.

- About The Johns Hopkins University. Facts And Statistics.

About The Johns Hopkins University. History.

> Johns Hopkins University Mission Statement.

The mission of The Johns Hopkins University is to educate its students and cultivate their capacity for life-long learning, to foster independent and original research, and to bring the benefits of discovery to the world.

> A Brief History of JHU.

The Johns Hopkins University opened in 1876, with the inauguration of its first president, Daniel Coit Gilman. “What are we aiming at?” Gilman asked in his installation address. “The encouragement of research … and the advancement of individual scholars, who by their excellence will advance the sciences they pursue, and the society where they dwell.”

The mission laid out by Gilman remains the university’s mission today, summed up in a simple but powerful restatement of Gilman’s own words: “Knowledge for the world.”

What Gilman created was a research university, dedicated to advancing both students’ knowledge and the state of human knowledge through research and scholarship. Gilman believed that teaching and research are interdependent, that success in one depends on success in the other. A modern university, he believed, must do both well. The realization of Gilman’s philosophy at Johns Hopkins, and at other institutions that later attracted Johns Hopkins-trained scholars, revolutionized higher education in America, leading to the research university system as it exists today.

After more than 130 years, Johns Hopkins remains a world leader in both teaching and research. Eminent professors mentor top students in the arts and music, the humanities, the social and natural sciences, engineering, international studies, education, business and the health professions. Those same faculty members, and their research colleagues at the university’s Applied Physics Laboratory, have each year since 1979 won Johns Hopkins more federal research and development funding than any other university.

The university has nine academic divisions and campuses throughout the Baltimore-Washington area. The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, the Whiting School of Engineering, the School of Education and the Carey Business School are based at the Homewood campus in northern Baltimore. The schools of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing share a campus in east Baltimore with The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The Peabody Institute, a leading professional school of music, is located on Mount Vernon Place in downtown Baltimore. The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies is located in Washington’s Dupont Circle area.

The Applied Physics Laboratory is a division of the university co-equal to the nine schools, but with a non-academic, research-based mission. APL, located between Baltimore and Washington, supports national security and also pursues space science, exploration of the Solar System and other civilian research and development.

Johns Hopkins also has a campus near Rockville in Montgomery County, Md., and has academic facilities in Nanjing, China, and in Bologna, Italy. It maintains a network of continuing education facilities throughout the Baltimore-Washington region, including centers in downtown Baltimore, in downtown Washington and in Columbia.

When considered in partnership with its sister institution, the Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System, the university is Maryland’s largest employer and contributes more than $10 billion a year to the state’s economy.

> Who Was Johns Hopkins

First things first: why the extra “S”? Because his first name was really a last name.

Johns Hopkins’ great-grandmother was Margaret Johns, the daughter of Richard Johns, owner of a 4,000-acre estate in Calvert County, Md. Margaret Johns married Gerard Hopkins in 1700; one of their children was named Johns Hopkins.

The second Johns Hopkins, grandson of the first, was born in 1795 on his family’s tobacco plantation in southern Maryland. His formal education ended in 1807, when his parents, devout Quakers, decided on the basis of religious conviction to free their slaves and put Johns and his brother to work in the fields. Johns left home at 17 for Baltimore and a job in business with an uncle, then established his own mercantile house at the age of 24.

He was an important investor in the nation’s first major railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, and became a director in 1847 and chairman of its finance committee in 1855.

Hopkins never married; he may have been influenced in planning for his estate by a friend, philanthropist George Peabody, who had founded the Peabody Institute in Baltimore in 1857.

In 1867, Hopkins arranged for the incorporation of The Johns Hopkins University and The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and for the appointment of a 12-member board of trustees for each. He died on Christmas Eve 1873, leaving $7 million to be divided equally between the two institutions. It was, at the time, the largest philanthropic bequest in U.S. history.

> Inaugural Address of Daniel Coit Gilman as first president of The Johns Hopkins University.

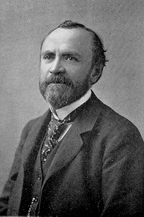

Daniel Coit Gilman was inaugurated as the first president of The Johns Hopkins University on Tuesday, Feb. 22, 1876, in the Academy of Music at Howard and Centre Streets in downtown Baltimore. Among the distinguished guests were the governor of Maryland, the mayor of Baltimore and representatives of a number of colleges and universities, including President Eliot of Harvard. The significance of the occasion was clearly stated by Reverdy Johnston Jr., chairman of the executive committee of the new university’s Board of Trustees, in his presentation of the new president. “We may say that the university s birth takes place today, and I do not think it mere sentiment should we dwell with interest upon its concurrence with the centennial year of our national birth, and the birthday of him who led the nation from the throes of battle to maturity and peace.” At 45, Daniel Coit Gilman then stepped to the podium to deliver his inaugural address, which was to set the tone for American higher education for the century to come.

If this assembly, with one voice, could utter the thought now uppermost, there would be a deep, quick, hearty acknowledgment of the bounty of Johns Hopkins.

His beneficence, so free, so great, so wise, promoting at once the physical, intellectual and moral welfare of his fellow-men, awakens universal surprise and admiration, and calls for our perpetual thanks.

In respect to the giver, I can say but little to you, the citizens of Baltimore, who knew him so well; who remember his industry, sagacity and intellectual force; who have tested his integrity, and found that his word was as good as his bond; who recall his foresight, his enterprise, and his belief in the future of this city and state; who recollect that more than once in financial crises he hazarded his own fortune for the protection of others; who heard, it may be from his own lips, the motives and hopes which prompted these royal gifts; who believe that great acquisitions involve great responsibilities, but who know how hard it was for one long accustomed to power to yield that power to others; to you, his fellow-citizens, who saw the steps by which this benefactor toiled upward to the temple of Fortune, and there unsatisfied, went higher, by more arduous steps, to the temple of Charity, where he bestowed his gifts.

While I leave to others the commemoration of our founder, you must let me refer to the tributes of admiration which his generosity has called out on the remotest shores of our own land, and in the most venerable shrines of European learning. The Berkeley laurel and the Oxford ivy may well be carved upon his brow when the sculptor shapes his likeness; for by wise men in the east and by rich men in the west, his gifts are praised as among the most timely, the most generous, and the most noble ever bestowed by one, for all.

The genesis of American munificence is a bright chapter of our history. From the days of the Puritan minister, who gave his name to our oldest University, and the days of the London merchant, who endowed the second college in New England, each generation has surpassed its predecessors. It is a striking coincidence that among the very earliest names on. this heraldic roll, is that which our foundation bears. The schools which Edward Hopkins, a colonial governor, established in 166o, by his will, and his gifts to Harvard, still keep alive his name and influence. So may the name of our founder live for more than two hundred years to come, and his gifts be immortal. Johns Hopkins might have used the very words of Edward Hopkins, who desired to bestow “some encouragement for the breeding up of hopeful youths, for the public service of the country in future times.”

We may conjecture a spiritual if not a physical descent in the line of Hopkins. In 1676, the name is written on the door of an endowed grammar school at New Haven, older than Yale, and second only to Harvard; in 1776, the name is signed to the Declaration of Independence; in 1876, it distinguishes a University Foundation. To our contemporary, we may apply the words with which the deeds of the colonial governor are recounted. After saying that his last will is an interesting monument of private friendship and public spirit, that friends and domestics were not forgotten, that his public gifts were “for the promotion of religion, science and charity,” the historian adds this eulogy: “Thus did this lofty and intellectual spirit devise and distribute blessings in his own age, and by his wisdom, prepare and make them perpetual for succeeding times.”

The Endowment

The total amount of the public gifts of Johns Hopkins, is more than seven million dollars. The sum of $3,500,000 is appropriated to a university; a like sum to a hospital; and the rest to local institutions of education and charity. Let us compare these benefactions with some others. Thirty years ago, when the gift of Abbott Lawrence to Harvard College was made known it was said to be “the largest amount ever given at one time during the life time of the donor to any public institution in this country,” — the amount was $50,000; the gift of Smithson, so well administered in Washington, amounted to over half a million; the foundation of Stephen Girard surpassed two million dollars.

You may see from these figures what great munificence has brought us together. So far as I can learn, the Hopkins foundation, coming from a single giver, is without a parallel in terms or in amount in this or any land. But beware of exaggeration. These gifts are often spoken of as if the whole, instead of the half, was intended for the university, and then as if an equal amount was given to the hospital; and so it happens that dreams of monumental structures and splendid piles and munificent salaries flit through the mind which can never become real. Do not forget how much wealth is accumulated by older colleges — in repute, experience and influence, and also in material things. The property of Harvard College is more than five million dollars; that of Yale must equal our endowment. The land investments of a university in the Northwest are said to exceed these values; and Ezra Cornell, while he lived, expected that the endowments at Ithaca would approach, if not surpass, the funds of Harvard. The income yielding funds of Harvard in 1875 were over three million; those of Yale near a million and a half. Even these figures look small compared with the accumulations of Oxford and Cambridge.

Now turn our capital into income. Our university fund yields a revenue of nearly $200,000. Let us compare this amount with the resources of our two richest colleges. Harvard, in 1874-5, (in all departments), received from tuition $168,541.72; from property, $218,715.30; a total of $387,257.02. The college alone, not including the library, the general administration, or any of the special departments, cost $187,713.20, which is nearly our whole income. Yale College reports its academical expenses (i.e., exclusive of those in the scientific, theological, law, medical and art departments), in 1874-5, as $126,073.56.

But all our revenue is not at once available; for, as the capital cannot be spent for buildings, some income must be reserved for this. Of course, the buildings will be good and costly. If now we deduct from our income, as a building fund, one hundred thousand dollars annually, it will take several years to accumulate the requisite amount. Of that which remains a large sum will be absorbed by taxation, administration and the purchase of books, instruments and collections. Thus it is evident that the educational income at present is not large. Its expenditure requires great discretion and prudence. The trustees are men of liberal views in respect to professional salaries, but they see as clearly as a schoolboy sees through a problem in short division that the larger the divisor, the less the quotient; the more salary, the less chairs; the more eminent and costly the teachers, the fewer can be secured. I wish that every one who sees the need of a great university, and who knows the range of human science, would take a pencil and distribute our income in the departments which he would like to see promoted here. If his experience is like mine, he will find that before his pencil has half gone down the column of sciences, the income has been twice expended.

I fear that these remarks are a little ungracious, and I would gladly repress them; but the private and public utterances of thoughtful men have been so vague as to what it is possible for the trustees of this university to accomplish at once, and our friends are so very generous in their expectations that I feel compelled, at the very outset, to utter a word of caution. If our physicists could bring us “Aladdin s lamp,” or our chemists produce “the philosopher s stone,” or our merchants give us “the widow s cruse,” our aspirations should not be checked by our restricted means; but, till the original benefaction is supplemented by other gifts, or the growth of Baltimore increases the value of our present investments, we must be contented with good work in a limited field.

Its Five-Fold Advantages

To many the magnitude of our founder s bounty seems its principal value; that is, in fact, but half its glory. With a self-renunciation which is rare and noble, he attached to the gift no burdensome condition or personal whim. The almoners of his bounty are restrained by no shackles bequeathed by a departed benefactor, as they enter upon their course bearing in the one hand the ointment of charity and in the other the lamp of science. His trustees are free — free to determine principles, to decide upon methods, to distribute income, to select professors, to summon students, and even to alter, from time to time, their own plans — as the enlightenment of the world bestows its radiance upon their undertaking.

In selecting trustees the choice of our founder fell upon those of his friends and acquaintances whom he believed would be free from a desire to promote, in their official action, the special tenets of any denomination or the platform of any political party In a land where almost every strong institution of learning is either “a child of the church” or “a child of the state,” and is thus liable to political or ecclesiastical control, he has planted the germ of a university which will doubtless serve both church and state the better because it is free from the guardianship of either. It was his wish — it is our wish — that here should be a seat of learning so attractive that at its threshold students would gladly cease to discuss sectarian animosities and political prejudices, in their eagerness for the acquisition of Knowledge and their search for Eternal Truth. As in olden time the courtier s and the peasant s sons laid aside their distinctive costumes when they donned the academic dress, let us hope that here the only badges will be those which mark the scholar.

Another advantage attends our foundation. It is established in a large town, in an old state, near to the financial and the political Capitals of the Republic; and at the junction of national highways which connect the North and the South, the East and the West. This is in fact a metropolis or middle city. Such geographical considerations will surely affect our future. Baltimore, moreover, is prepared for this foundation. Professional schools of law, medicine and theology already attract large numbers of students. Technical instruction in the useful arts is to some extent provided in the Maryland Institute. The votaries of the natural sciences are associated in an Academy, which only needs an endowment to enable it to take rank with kindred societies else-where. The city, with a liberality which is praised at home and abroad, maintains two excellent high schools for young ladies, and for young men a City College, so well organized, so well taught and so well supported, that it relieves our foundation of doing much which is called “collegiate” in distinction from “university” work. There are good private schools. There are excellent collections of paintings and rare opportunities for the study of music, both as a science and an art. More than all this the foundation of George Peabody, in which a capital of a million and a quarter of dollars is forever set apart for the pro- motion of culture, has now, with increasing strength, survived the perils of infancy, and gained a place among the very best establishments to be found in any part of our land. Its library is extraordinary for our country; not because of its size, (some 60,000 volumes) but because it has been selected with an experienced eye, among the most modern and most useful of the publications of the world.

The advantage which will come to the new University in its medical department from the establishment of a hospital, on a separate but allied foundation, is most obvious. Obvious though it is, the most enlightened can not over-estimate its value. If so large a sum as the hospital fund ($3,500,000) were consecrated under any circumstances to the relief of suffering, the promotion of health, and the preservation of life — humanity would rejoice; but when such a foundation is connected with a university, so that on the one hand it commands all the resources of human learning, and on the other makes known through accomplished teachers the results of its experience, we may confidently expect that its influence for good will be more than doubled; that its immediate work in the care of the sick and wounded will be better done than would otherwise be possible; and that its remedial and preventive agencies will extend to thousands who may never come within its walls, but whose ills will be relieved by those taught here.

The timeliness of our foundation is the last of the advantages which I shall name. We begin our work after discussions lasting for a generation respecting the aims, methods, deficiencies, and possibilities of higher education in this country; after numerous experiments, some with oil in the lamps and some without; after costly ventures of which we reap the lessons, while others bear the loss; after Jefferson, Nott, Wayland, Quincy, Agassiz, Tappan, Mark Hopkins, Woolsey, have completed their official services and have given us their supreme decisions; while the strong successors of these strong men, Eliot, Porter, Barnard, White, Angell and McCosh, are still up on the controversial platform; we begin after the national bounty has for fourteen years, under the far-reaching bill of Senator Morrill of Vermont, promoted scientific education; and after scores of wealthy men have bestowed many million dollars for the foundation of new institutions of the highest sort.

Discussions Elsewhere

Educational discussions and movements are not restricted to our new country. In old England, questions like these are constantly rife, (in addition to many of purely local interest): How may professorships in the old universities be restored to the dignity or influence, of which they have been in part deprived by the excessive preponderance of collegiate instruction; how may the university influences be extended to all the large towns; how may science gain a more generous recognition in the ancient seats of learning; how may endowments for research be established without leading to sinecure fellowships; how may ecclesiastical fetters be removed from academic institutions; how may the universities, by their systems of local examinations, best promote the welfare of the preparatory schools, or the training of young persons who are not likely to enter the university; how may the university better provide for the innumerable modern callings, which lie outside of the old “professions” but require an equal culture.

In France, there has not been since the Revolution, I presume, such interest in the promotion of universities as now. I pronounce no opinions, but I call attention to the remarkable law which was passed last year, relinquishing the exclusiveness of a State foundation, and declaring university instruction to be free. Those who have hitherto been oppressed, as they have thought, by a hard law, now seize with alacrity the opportunity to found new institutions, and the offerings of the faithful are freely poured out to restore to the Church those intellectual agencies from which she has been cut off.

At a distance, Germany seems the one country where educational problems are determined; not so, on a nearer look. The thoroughness of the German mind, its desire for perfection in every detail, and its philosophical aptitudes are well illustrated by the controversies now in vogue in the land of universities. In following, as we are prone to do in educational matters, the example of Germany, we must beware lest we accept what is their cast off; lest we introduce faults as well as virtues, defects with excellence. Some of the ablest men in the new empire I are now questioning whether “the Real School” system, after a trial of so many years, is justified of its works — and whether “the gymnasium,” somewhat modified, should not be the training place of all who seek a higher culture. Others are questioning whether it is not a mistake to maintain polytechnic schools, and special schools of agriculture, forestry, mining, etc., apart from the universities; and whether it would not be better to combine the higher educational foundations under one direction and in one centre. Some of the best scientific men declare their belief that the university instruction in science, following the gymnastic discipline, is better far as a preparation for what are called the modern pursuits, than the training which is given by the Real school and the Polytechnic, and so they assert that an exaggerated value has been attached to technical training.

I only allude to these discussions in passing. It would take many hours to unfold them. But it is well to bear in mind that the most enlightened institutions in our country, and the most enlightened countries in Europe, are those in which educational discussions are now most lively; and it behooves us, as we engage in a new undertaking, to listen, ponder, and observe; and above all to be modest in the announcement of our plans. It should make the authorities cautious in offering, and the public cautious in demanding a completed scheme for the establishment of a university in Baltimore.

Our caution is none the less needed when we remember that at the present moment Americans are engaged in promoting the institutions of higher education in Tokyo, Peking and Beirout, in Egypt and the Hawaiian Isles. The oldest and the remotest nations are looking here for light. W7hat is the significance of all this activity? It is a reaching out for a better state of society than now exists; it is a dim but an indelible impression of the value of learning; it is a craving for intellectual and moral growth; it is a longing to interpret the laws of creation; it means a wish for less misery among the poor, less ignorance in schools, less bigotry in the temple, less suffering in the hospital, less fraud in business, less folly in politics; it means more study of nature, more love of art, more lessons from history, more security in property, more health in cities, more virtue in the country, more wisdom in legislation, more intelligence, more happiness, more religion.

The Higher Education

The institutions which are founded in modern society for the promotion of superior education may be grouped in five classes: 1, UNIVERSITIES; 2, LEARNED SOCIETIES; 3, COLLEGES; 4, TECHNICAL SCHOOLS; and 5, MUSEUMS, (including literary and scientific collections). It is important that the fundamental ideas of these various institutions should be borne in mind.

The University is a place for the advanced special education of youth who have been prepared for its freedom by the discipline of a lower school. Its form varies in different countries. Oxford and Cambridge universities, are quite unlike the Scotch, and still more unlike the Queen s University in Ireland; the University of France has no counterpart in Germany; the typical German universities differ much from one another. But while forms and methods vary, the freedom to investigate, the obligation to teach, and the careful bestowal of academic honors are always understood to be among the university functions. The pupils are supposed to be wise enough to select, and mature enough to follow the courses they pursue.

The Academy, or Learned Society, of which the Institute of France, with its five academies, and the Royal Society of London, are typical examples — is an association of learned men, selected for their real or reputed merits, who assemble for mutual instruction and attrition, and who publish from time to time the papers they have received and the proceedings in which they have engaged. The University is also an association of learned men, but the bond which holds them together differs essentially from that of the academy. In the universities teaching is essential, research important; in academies of science research is indispensable, tuition rarely thought of. The College implies, as a general rule, restriction rather than freedom; tutorial rather than professorial guidance; residence within appointed bounds; the chapel, the dining hail, and the daily inspection. The college theoretically stands in loco parentis; it does not afford a very wide scope; it gives a liberal and substantial foundation on which the university instruction may be wisely built.

The Technical Schools present the idea of preparation for a specific calling, rather than the notion of a liberal culture. They have in view the imparting of knowledge which will be useful in the practice of a profession, and often set forward as a motive, and assured introduction to the openings which are ready for those who have received their training.

Museums, Galleries and Libraries, (of which the British Museum is the grandest type), are indeed connected with the other agencies we have named, but they often have an independent existence. They fulfill a two-fold purpose. They preserve and store away the treasures of art, literature and science; and they distribute widely among the people those seeds of culture which are developed by artistic, historic and scientific acquisitions.

Thus we say that the Academy of Sciences promotes the intellectual attrition of the most learned men; the University favors the liberal and special culture of advanced students; the College trains aspiring youth for their future intellectual freedom; the Technical School affords a good preparation for a specific vocation; and the Museum provides materials for study, adapted like the world itself, to interest the most profound and the most superficial.

Now it is clear that we might have a University without the four adjuncts I have named; and we might have the four accessories without the University, but practically wherever a strong University is maintained, these four-fold agencies revolve around it. It is the sun and they are the planets. In Baltimore you have hitherto had a College, an Academy of Sciences, Professional Schools and a Scholars Library, but you have not had such an endowed University as that which is now inaugurated.

Indeed this new foundation might almost adopt the preamble which John Calvin prefixed to the statutes of the Academy of Geneva: “Verily hath God heretofore endowed our commonwealth with many and notable adornments, yet hath it to this day had to seek abroad for instruction in good arts and disciplines for its youth, with many lets and hindrances.”

But soon I hope we may add what Erasmus said at Oxford: “It is wonderful what a harvest of old volumes is flourishing here on every side; there is so much of erudition, not common and trivial, but recondite, accurate and ancient, both Greek and Latin, that I should not wish to visit Italy, except for the gratification of traveling.”

The earliest foundations in our country were colleges, not universities. Scholars were often graduated early in this century at the age when now they enter. Earnest efforts are now making to establish universities. Harvard, with a boldness which is remarkable, has essentially given up its collegiate restrictions and introduced the benefits of university freedom; Yale preserves its college course intact, but has added a school of science and developed a strong graduate department; the University of Michigan and Cornell University quite early adopted the discipline of universities, and already equal or pass not a few of their elder sisters; the University of Virginia from its foundation has upheld the university in distinction from the college idea. The cry all over the land is for university advantages, not as superseding but as supplementing collegiate discipline.

As we, my friends, are called upon to develop a university, it becomes important not only to distinguish its essential idea from that of any other institution, but also to form a clear conception of its special province; of various plans which have governed its organization; of the good which it promotes; of the questions which are settled; of the questions which are not settled; and especially of the bearing of all these points on our land, our times, our foundation. Thus only shall we make a contribution to the intellectual agencies of this country, and add a positive gain to American learning and education in the second century of the Republic.

The tenor of my remarks has implied perhaps more diversity of opinion than really exists in respect to universities. The truth is, most institutions are not free to build anew; they can only readjust. It has been playfully said that “traditions and conditions” impede their progress. But whatever may be the concrete difficulties, on many abstract principles there is little need of controversy. Our effort will be to accept that which is determined, — to avoid that which is obsolescent, to study that which is doubtful, — “slowly making haste.”

Twelve Points Determined

Is, then, anything settled in respect to university education? Much, very much. Can we draw a statement of what is agreed upon? At any rate we can try.

The schedule will include twelve points on which there seems to be a general agreement.

- All sciences are worthy of promotion; or in other words, it is useless to dispute whether literature or science should receive most attention, or whether there is any essential difference between the old and the new education.

- Religion has nothing to fear from science, and science need not be afraid of religion. Religion claims to interpret the word of God, and science to reveal the laws of God. The interpreters may blunder, but truths are immutable, eternal and never in conflict.

- Remote utility is quite as worthy to be thought of as immediate advantage. Those ventures are not always most sagacious that expect a return on the morrow. It sometimes pays to send our argosies across the seas; to make investments with an eye to slow but sure returns. So it is always in the promotion of science.

- As it is impossible for any university to encourage with equal freedom all branches of learning, a selection must be made by enlightened governors, and that selection must depend on the requirements and deficiencies of a given people, in a given period. There is no absolute standard of preference. What is more important at one time or in one place may be less needed elsewhere and otherwise.

- Individual students cannot pursue all branches of learning, and must be allowed to select, under the guidance of those who are appointed to counsel them. Nor can able professors be governed by routine. Teachers and pupils must be allowed great freedom in their methods of work. Recitations, lectures, examinations, laboratories, libraries, field exercises, travels, are all legitimate means of culture.

- The best scholars will almost invariably be those who make special attainments on the foundation of a broad and liberal culture.

- The best teachers are usually those who are free, competent and willing to make original researches in the library and the laboratory.

- The best investigators are usually those who have also the responsibilities of instruction, gaining thus the incitement of colleagues, the encouragement of pupils, the observation of the public.

- Universities should bestow their honors with sparing hand; their benefits most freely.

- A university cannot be created in a day; it a slow growth. The University of Berlin has been quoted as a proof of the contrary. That was indeed quick success, but in an old, compact country, crowded with learned men eager to assemble at the Prussian court. It was a change of base rather than sudden development.

- The object of the university is to develop character — to make men. It misses its aim if it produced learned pedants, or simple artisans, or cunning sophists, or pretentious practitioners. Its purport is not so much to impart knowledge to the pupils, as whet the appetite, exhibit methods, develop powers, strengthen judgment, and invigorate the intellectual and moral forces. It should prepare for the service of society a class of students who will be wise, thoughtful, progressive guides in whatever department of work or thought they may be engaged.

- Universities easily fall into ruts. Almost every epoch requires a fresh start.

If these twelve points are conceded, our task is simplified, though it is still difficult. It is to apply these principles to Baltimore in 1876.

We are trying to do this with no controversy as to the relative importance of letters and science, the conflicts of religion and science, or the relation of abstractions and utilities; our simple aim is to make scholars, strong, bright, useful and true.

This brings me to the question which has brought you here.

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY: what will be its scope? The Trustees have decided to begin with those things which are fundamental and move gradually forward to those which are accessory.

They will institute at first those chairs of language, mathematics, ethics, history and science which are commonly grouped under the name of the Department of Philosophy.

The Medical Faculty will not long be delay that of Jurisprudence will come in time; that Theology is not now proposed.

I have lately met with an ancient saying in respect to the development of a youth. “At five,” the precept read, “he was to study the Scriptures; at ten, the Mishna; at thirteen, the Talmud; at eighteen to marry; at twenty, to attain riches; at thirty strength; at forty, prudence, and so on to the end.” So we begin with the essential, proceed to the important, expect enlarged endowments, strength, prudence and the other virtues as we grow in years.

In organizing a faculty, the first chairs to be filled are those which everywhere, always people in the modern Republic of Letters, are regarded as needful. ‘We must provide for the study of languages, ancient and modern; math and applied; science, natural and physical. All this is assumed as granted. But if we should do all this well and do nothing more, we should not add much to the intellectual resources of the country. ‘We must ask ourselves other questions: What special departments of learning are now neglected in the higher institutions of this country? What can we provide for? In what order shall we proceed?

These problems require profound consideration; their answer must depend on manifold conditions; their solution will doubtless be the result of many counsels. Partly to elicit the suggestions of other teachers, and partly to exhibit what seem to me the inevitable demands of this place, I shall suggest some of the departments of higher education which seem to require attention from us. I cannot now tell all I think and hope.

As a fundamental proposition, bear in mind that we shall aim to choose the fittest teachers, and shall then expect them to do their very best work. None but a college officer will appreciate all that this brief sentence carries with it.

The Medical Sciences & Biology

When we turn to the existing provisions for medical instruction in this land and compare them with those of European universities; when we see what inadequate endowments have been provided for our medical schools, and to what abuses the system of fees for tuition has led; when we see that in some of our very best colleges the degree of Doctor of Medicine can be won in half the time required to win the degree of Bachelor of Arts; when we see a disposition to treat diplomas as blank paper by the civilians at home and the profession abroad; when we read the reports of the medical faculty in their own professional journals; when we see the difficulties which have been encountered at Harvard, Yale,. and elsewhere, in late attempts to reorganize the medical schools; when we see the prevalence of quackery vaunting its diplomas, it is clear that something should be done. Then, turning to the other side of the picture, when we see what admirable teachers have given instruction among us in medicine and surgery; what noble hospitals have been created; what marvelous discoveries in surgery have been made by our countrymen; what ingenious instruments they have contrived; what humane and skillful appliances they have provided on the battlefield; what admirable measures are in progress for the advancement of hygiene and the promotion of public health; when we see what success has attended recent efforts to reform the system of medical instruction; when we observe all this, we need not fear that the day is distant — we may rather rejoice that the morning has dawned which will see endowments for medical science as munificent as those now provided for any branch of learning, and schools as good as those which are now provided in any other land.

It will doubtless be long, after the opening of the University, before the opening of the Hospital, and this interval may be spent in forming plans for the Department of Medicine.

But in the meantime we have an excellent opportunity to provide instruction antecedent to the professional study of medicine. At the present moment medical students avoid the ordinary colleges. A glance at the catalogues is enough to show that the usual classical or academic course is unattractive to such scholars. The reasons need not be given here. But who can doubt that a course may be maintained, like that already begun in the Sheffield School at New Haven, which shall train the eye, the hand and the brain, for the later study of medicine? Such a course should include abundant practice in the laboratories of chemistry, zoology and physics; the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the lower forms of life; an investigation of the elements of physics and mechanics, and of climatic and meteorological laws; the geographical distribution of disease; the remedial agencies of nature and art; and, besides these scientific studies, the student should acquire enough of French and German to follow with ease European science, and enough Latin for his professional needs. In other words, in our scheme of a university, great prominence should be given to the studies which bear upon Life, — the group now called Biological Sciences.

Such facilities as are now afforded under Huxley in London, and Rolleston at Oxford, and Foster at Cambridge, and in the best German universities, should here be introduced. They would serve us in the training of naturalists, but they would serve us still more in the training of physicians. By the time we are ready to open a school of medicine, we might hope to have a superior, if not a numerous, body of aspirants for one of the noblest callings to which the heart and head can be devoted.

When the medical department is organized, it should be independent of the income derived from student fees, so that there may not be the slightest temptation to bestow the diploma on an unworthy candidate; or rather let me say, so that the Johns Hopkins diploma will not be a greenback, but will be worth its face in the currency of the world.

The Modern Humanities

Next to the study of Man, in his relations to Nature, comes the study of Man in his relations to Society. By this I mean his history, as exemplified in the monuments of literature and art, in language, laws and institutions, in manners, morals and religion. More particularly still I refer to the principles of good government, including jurisprudence on the one hand, and political economy on the other. Legislation, taxation, finance, crime, pauperism, municipal government, morality in public and private affairs, are among the special topics. The civil law, international law, the early history of institutions, in short, the history of civilization and the requirements of a modern State come under this department. If we may judge from what is said by some of the best publicists, the United States, at this moment, is suffering from the neglect of these studies. There is a call for men who have been trained by other agencies than the caucus for the discussion of public affairs; men who know what the experience centre of population, where fifteen or twenty thousand persons are assembled, should have the services of a competent scientific engineer. He must of course have a general mathematical training; but he should also know how to use these fundamental principles in municipal affairs, in the preparation of exact maps, in the determination of the supplies of water, and the methods of drainage, in the construction of roads, boulevards, pleasure grounds and parks, the building of wharves and docks, the supervision of gas works and fire engines, the erection of public buildings, monuments and places of assembly. There should be a recognized preparation for this work of civic or municipal engineering — in distinction from civil engineering, which is a more vague and general term, including perhaps the subordinate branches to which I have referred.

Architecture is closely connected with this department. So far as I am aware there are now, in this new country where so much building is in progress, but two schools for the professional study of this, the first of arts.

I can hardly doubt that such arrangements as we are maturing will cause this institution to be a place for the training of professors and teachers for the highest academic posts; and I hope in time to see arrangement made for the unfolding of the philosophy, principles and methods of education in a way which will be of service to those who mean to devote their lives to the highest departments of instruction.

But in forming all these plans we must beware lest we are led away from our foundations; lest we make our schools technical instead of liberal; and impart a knowledge of methods rather than of principles. If we make this mistake, we may have an excellent Polytechnicum but not a University.

The Faculty and Students

– Who shall our teachers be?

This question the public has answered for us; for I believe there is scarcely a preeminent man of science or letters, at home or abroad, who has not received a popular nomination for the vacant professorship. Some of these candidates we shall certainly secure, and their names will be one by one made known. But I must tell you, in domestic confidence, that it is not an easy task to transplant a tree which is deeply rooted. It is especially hard to do so in our soil and climate. Though a migratory people, our college professors are fixtures. Such local college attachments are not known in Germany; and the promotions which are frequent in Germany are less thought of here. When we think of calling foreign teachers, we encounter other difficulties. Many are reluctant to cross the sea; and others are, by reason of their lack of acquaintance with our language and ways, unavailable. Besides we may as well admit that London, Paris, Leipsic, Berlin and Vienna, afford facilities for literary and scientific growth and influence, far beyond what our country affords. Hence, ‘it is probable that among our own countrymen, our faculty will be chiefly found.

I wrote, not long ago, to an eminent physicist, presenting this problem in social mechanics, for which I asked this solution. “We cannot have a great university without great professors till we have a great university: help us from this dilemma.” Let me tell his answer: “Your difficulty,” he says, “applies only to old men who are great; these you can rarely move; but the young men of genius, talent, learning and promise, you can draw. They should be your strength.”

The young Americans of talent and promise – there is our strength, and a noble company they are! We do not ask from what college, or what state, or what church they come; but what do they know, and what can they do, and what do they want to find out.

In the biographies of eminent scholars, it is curious to observe how many indicated in youth preeminent ability. Isaac Casaubon, whose name in the sixteenth century shed lustre on the learned circles of Geneva, Montpellier, Paris, London, and Oxford, began as professor of Greek at the age of twenty-two; and Heinsius, hey Leyden contemporary, at eighteen. It was at the age if twenty-eight, that Linnaeus first published in Systema Natur’. Cuvier was appointed a professor in Paris at twenty-six, and, a few months later, a member of the Institute. James Kent, the great commentator on America law, began his lectures in Columbia College at the age of thirty- one. Henry was not far from thirty years of age when he made his world-renowned researches in electro-magnetism; and Dana’s great work on mineralogy was first published before he was twenty-five years old, and about four years after he graduated at New Haven. Look at the Harvard list: -Everett was appointed Professor of Greek at twenty-one; Benjamin Peirce of Mathematics at twenty-four; and Agassiz was not yet forty when he came to this country. For fifty years Yale College rested in three men selected in their youth by Dr. Dwight, and almost simultaneously set at work; Day was twenty-eight, Silliman, twenty-three, and Kingsley, twenty-seven, when they began their professorial lives. The University of Virginia, early in its history, attracted foreign teachers, who were all young men.

We shall hope to secure a strong staff of young men, appointing them because they have twenty years before them; selecting them on evidence of their ability; increasing constantly their emoluments, and promoting them because of their merit to successive posts, as scholars, fellows, assistants, adjuncts, professors and university professors. This plan will give us an opportunity to introduce some of the features of the English fellowship and the German system of privat-docents; or in other words, to furnish positions where young men desirous of a university career may have a chance to begin, sure at least of a support while awaiting for promotion.

Our plans begin but do not end here. As men of distinction, who have won the highest rank in their callings, are known to be free, we shall invite them to come among us.

For a time, at least, we shall also look to the faculties of other colleges for occasional help. Many years ago, among the plans for establishing a university, in distinction from a college, at Cambridge, Professor Peirce proposed that various colleges should send up for a portion of the year, and for a term of years, their best professors, who should receive a generous acknowledgment for this service, and good opportunities for work, but should not renounce their college homes. Without having heard of his plan, which I think had not been made public, the Trustees of the Johns Hopkins University have worked out a kindred scheme. They propose to ask distinguished professors from other colleges to come to us during a term of years, each to reside here for an appointed time, and be accessible, publice et privatim, both in the lecture room and the study.

– Where do we look for students?

At first, at home, in Baltimore and Maryland; then, in the States adjacent; then, in the regions of our country where by the desolations of war, educational foundations have been impaired; and presently, according to the renown of the faculty, which we are able to bring here, and the completeness of the establishment, we hope that our influence will be national.

Of what grade will they be? Mature enough to be profited by university education. The exact standard is not yet fixed. It must depend on the colleges and schools around us; there must be no gap in the system, and we must keep ahead, but the discussions now in progress, respecting the City College, Agricultural College and St. John s College, must delay our announcements. Our standard will doubtless be as high as the community requires.

– What will the buildings be?

At first, temporary, but commodious; in the heart of the city, accessible to all; and fitted for lectures, laboratories, library and collections:. At length, permanent, on the site at Clifton; not a medieval pile, I hope, but a series of modern institutions; not a monumental, but a serviceable group of structures. The middle ages have not built any cloisters for us; why should we build for the middle ages? In these days laboratories are demanded on a scale and in a variety hitherto unknown, for chemistry, physics, geology and mineralogy, comparative anatomy, physiology, pathology. Oxford with its New Museum; Cambridge with its Cavendish laboratory; Owens College with its excellent work-rooms; South Kensington with the new apartments of Huxley and Frankland; Leipsic, Vienna, Berlin, all afford illustrations of the kind of structures we shall need. Already measures have been initiated for the improvement of Clifton as a university site. Although it will take time to develop the plans, I hope that we shall all live to see the day when the simplicity, the timeliness, and the strength which characterized our founder s gift, will be also apparent in the structures which his trustees erect; and when that site, beautiful in itself and already well planted, may be, in fact, an academic grove, with temples of learning, so appropriate, so true, and so well built that no other ornament will be essential for beauty, and yet that in their neighborhood no work of art will be out of place.

– Our affiliations deserve mention. Already harmonious relations have been established between this University and the Peabody Institute, the Academy of Sciences, and the City College, and the departments of State and City Education. I may also add that the authorities of the scientific institutions in Washington have evinced in many ways good will toward their new ally in Baltimore. As this University grows, we may anticipate perpetual advantages from its proximity to the national- capital, where the Smithsonian Institution, the Engineer Corps, the Naval Observatory, the Coast Survey, the Signal Service the Botanical Gardens the Congressional Library, the National Museum, the Territorial Surveys, the Army Medical and Surgical Collections, and the Corcoran Art Gallery are such powerful instruments for the advancement of science, literature and art.

The relation of this University to the higher education of women has not been as yet discussed by the Trustees, and doubtless their future conclusions will depend very much upon the way in which the subject is brought forward. I am not at liberty to speak for them, but personally have no hesitation in saying that the plans pursued in the University of Cambridge (England), especially in the encouragement of GIRTON College, seem likely to afford a good solution of a problem which is not without difficulty, however, it is approached. Of this I am certain, that they are not among the wise, who depreciate the intellectual capacity of women, and they are not among the prudent, who would deny to women the best opportunities for education and culture. I trust the day is near when some one, following the succession of Peabody and Hopkins, will institute here a “Girton College,” which may avail itself of the advantages of the Peabody and Hopkins foundations, without obliging the pupils to give up the advantages of a home, or exposing them to the rougher influences which I am sorry to confess are still to be found in colleges and universities where young men resort. For the establishment in Baltimore of such a hail as Girton I shall confidently look.

The University Freedom

If we would maintain a university, great freedom must be allowed both to teachers and scholars. This involves freedom of methods to be employed by the instructors on the one hand, and on the other, freedom of courses to be selected by the students.

But this freedom is based on laws, — two of which cannot be too distinctly or too often enunciated. A law which should govern the admission of pupils is this, that before they win this privilege they must have been matured by the long, preparatory discipline of superior teachers, and by the systematic, laborious, and persistent pursuit of fundamental knowledge; and a second law, which should govern the work of professors, is this, that with unselfish devotion to the discovery and advancement of truth and righteousness, they renounce all other preferment, so that, like the greatest of all teachers, they may promote the good of mankind.

I see no advantage in our attempting to maintain the traditional four-year class-system, of the American colleges. It has never existed in the University of Virginia; it is modified, through not nominally given up at Harvard; it is not known in the English, French or German Universities. It is a collegiate rather than a university method. If parents or students desire us to mark out prescribed courses, either classical ir scientific, lasting four years, it will be easy to do so. But I apprehend that many students will come to us excellent in some branches of liberal education and deficient in others-good perhaps in Greek, Latin and mathematics; deficient in chemistry, physics, zoology, history, political economy, and other progressive sciences. I would give to such candidates on examination, credit for their attainments, and assign them in each study the place foe which they are fitted. A proficient in Plato may be a tyro in Euclid. Moreover, I would make attainments rather than times the condition of promotion; and I would encourage every scholar to go forward rapidly or go forward slowly according to the fleetness of his foot and his freedom from impediment. In other words, I would have our University seek the good of individuals rather than of classes.

The sphere of a university is sometimes restricted by its walls, or is limited to those who are enrolled on its lists. There are three particulars in which we shall aim at extra- mural influence: first, as an examining body, ready to examine and confer degrees or other academic honors on those who are trained elsewhere; next, as a teaching body, by opening to educated persons (whether enrolled as students or not) such lectures as they may wish to attend, under certain restrictions — on the plan of the lectures in the high seminaries of Paris; and, finally, as in some degree at least a publishing body, by encouraging professors and lecturers to give to the world in print the results of their researches.

Conclusion

Let us now, as we draw near the close of this allotted hour, turn from details and recur to general principles.

– What are we aiming at?

An enduring foundation; a slow development; first local, then regional, then national influence; the most liberal promotion of all useful knowledge; the special provision of such departments as are elsewhere neglected in the country; a generous affiliation with all other institutions, avoiding interferences, and engaging in no rivalry; the encouragement of research; the promotion of young men; and the advancement of individual scholars, who by their excellence will advance the sciences they pursue, and the society where they dwell.

No words could indicate our aim more fitly than those by which John Henry Newman expresses his “Idea of the University,” in a page burning with enthusiasm, to which I delight to revert.

– What will be our agencies?

A large staff of teachers; abundance of instruments, apparatus, diagrams, books, and other means of research and instruction; good laboratories, with all the requisite facilities; accessory influences, corning both from Baltimore and Washington; funds so unrestricted, charter so free, schemes so elastic, that as the world goes forward, our plans will be adjusted to its new requirements.

– What will be our methods?

Liberal advanced instruction for those who want it; distinctive honors for those who win them; appointed courses for those who need them; special courses for those who can take no other; a combination of lectures, recitations, laboratory practice, field work and private instruction; the largest discretion allowed to the Faculty consistent with the purposes in view; and, finally, an appeal to the community to increase our means, to strengthen our hands, to supplement our deficiencies, and especially to surround our scholars with those social, domestic and religious influences which a corporation can at best imperfectly provide, but which may be abundantly enjoyed in the homes, the churches and the private associations of an enlightened Christian city.

CITIZENS OF BALTIMORE AND MARYLAND: This great undertaking does not rest upon the Trustees alone; the whole community has a share in it. However strong our purposes, they will be modified, inevitably, by the opinions of enlightened men; so let parents and teachers incite the youth of this commonwealth to high aspirations; let wise and judicious counsellors continue their helpful suggestions, let skillful writers, avoiding captiousness on the one hand and compliment on the other, uphold or refute or amend the tenets here announced; let the guardians of the press diffuse widely a knowledge of the benefits which are here provided; let men of means largely increase the usefulness of this work by their timely gifts.

At the moment there is nothing which seems to me so important, in this region, and indeed in the entire land, as the promotion of good secondary schools, preparatory to the universities. There are old foundations in Maryland which require to be made strong, and there is room for newer enterprises, of various forms. Every large town should have an efficient academy or high school; and men of wealth can do no greater service to the public than by liberally encouraging, in their various places of abode, the advanced instruction of the young. None can estimate too highly the good which came to England from the endowment of Lawrence Sheriff at Rugby, and of Queen Elizabeth s school at Westminster, or the value to New England of the Phillips foundations in Exeter and Andover.

Every contribution made by others to this new University will enable the Trustees to administer with greater liberality their present funds. Special foundations may be affiliated with our trust, for the encouragement of particular branches of knowledge, for the reward of merit, for the construction of buildings; and each gift, like the new recruits of an army, will be the more efficient because of the place it takes in an organized and efficient company. It is a great satisfaction in this world of changes and pecuniary loss to remember what safe investments have been made at Harvard and Yale, and other old colleges, where dollar for dollar is still shown for every gift.

The atmosphere of Maryland seems favorable to such deeds of piety, hospitality and “good-will to men.” George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore, comes here, returns to England and draws up a charter which becomes memorable in the annals of civil and religious liberty, for which, “he deserves to be ranked,” (as Bancroft says), “among the most wise and benevolent lawgivers of all ages;” among the liberals of 1776 none was bolder than Charles Carroll of Carrollton; John Eager Howard, the hero of Cowpens, is almost equally worthy of gratitude for the liberality of his public gifts; John McDonogh, of Baltimore birth, bestows his fortune upon two cities for the instruction of their youth; George Peabody, resident here in early life, comes back in old age to endow an Athen’um, and begins that outpouring of munificence which gives him a noble rank among modern philanthropists; Moses Sheppard bequeaths more than half a million for the relief of mental disease; Rinehart, the teamster boy, attains distinction as a sculptor, and bestows his well-won acquisitions for the encouragement of art in the city of his residence; and a Baltimorean still living, provides for the foundation of an astronomical observatory in Yale College; while Johns Hopkins lays a foundation for learning and charity, which we celebrate to- day.

Let me enlist attention from THE YOUTH OF BALTIMORE. For you, my young friends, these great advantages are provided. What will be your response? Is there not among you some bookbinder s boy, like Michael Faraday, who will be led by our Royal Institution to a line of research for which the world will be better; is there not here some private teacher, like Cuvier, or some minister s son, like Agassiz, burning with a desire to pursue the study of natural history; is there not some sophomore in college, like Alexander Hamilton, ready to discuss the questions of public finance, eager to be trained by a master economist; is there not in Baltimore a genius in mathematics, like Gauss, who at three years old corrected his father s arithmetic, at eighteen entered the University of Gottingen where he made a discovery which had puzzled geometers “from the days of Euclid,” and who died at seventy- seven, among the most eminent of his time? If so, I say it is for you, bright youths, that these doors are opened. Enter the armory and equip yourselves.

GENTLEMEN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES: The duty you assigned me of unfolding your plans is now imperfectly discharged. I hope that I have not struck too low a key in speaking of the opportunities, and on the contrary, that I have not said anything in rivalry or boast. If I have seemed cautious, you are sanguine, invigorated by the force of a lofty purpose, and the comforting consciousness of ample means. If I have seemed sanguine, you are cautious, aware that there are other institutions, older, richer, and more experienced than this, whose example we must study, and whose help we must seek.

Before concluding, I repeat in public the assent which I have privately made to your official overtures. In speaking of your freedom from sectarian and political control, you expressed to me a hope that this foundation should be pervaded by the spirit of an enlightened Christianity; while you proposed to train young men for the service of the State and the responsibilities of public life, you hoped the University would never engage in sectional, partisan and provincial animosities. In both these propositions I now as then express my cordial and entire concurrence.

Our work now begins. This place is felicitous, midway between the extremes of North and South, and redolent of memories of men and women whose names the world will never forget. This day is suggestive, reminding us of one whose wise moderation wrought great achievements. This year is auspicious, inviting us to sink political animosities in sentiments of fraternal good will, and of patriotic regard for a re-united republic. This company is inspiring; the city, the state, and the older seats of learning, far and near, here express their good will. Most welcome among their utterances are the words with which the oldest college in the land extends its fellowship to the youngest of the band.

So, friends and colleagues, we launch our bark upon the Patapsco, and send it forth to unknown unknown seas. May its course be guided by looking to the heavens and the voyage promote the glory of God and the good of Mankind.

Permit one word of a personal character before I take my seat. My life thus far has been spent in two universities, one full of honors, the other of hopes; one led by experience, the other by expectations. May the lessons of both, the old and the new, be wisely blended here. There is not a place in all the land which I should be so glad to fill as that in which I have been placed by your favorable consideration; but the burdens will be heavy unless your kind indulgence is continued. Standing almost within sight of the monument which has given a name to this city, do not deem it presumptuous if I adopt the words which Washington addressed to the citizens of Baltimore in 1789, and say on his memorial day, as he said then:

“I know the delicate nature of the duties incident to the part I am called to perform, and I feel my incompetence without the singular assistance of Providence to discharge them in a satisfactory manner; but having undertaken the task from a sense of duty, no fear of encountering difficulties, and no dread of losing popularity shall ever deter me from pursuing what I take to be the true interest of my country.”

> Johns Hopkins University. Chronology.

1795

May 19: Johns Hopkins is born at Whitehall, his family’s tobacco plantation, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

1867

August 24: Johns Hopkins incorporates both his university and his hospital.

1868

Peabody Academy of Music opens under the direction of Lucien H. Southard with 148 students. In 1857 George Peabody had proposed the establishment of an institute in Baltimore to be comprised of a library, art gallery, academy of music, and a lecture series. Peabody had attended the dedication of the institute’s first building on October 25, 1866, and had declared, “I never experienced from the citizens of Baltimore anything but kindness, hospitality and confidence.” Building had been completed in 1861, but the Civil War had intervened.

1870

June 13: First meeting of the trustees for the university and hospital under the charters of 1867. Galloway Cheston, Baltimore financier and philanthropist and one of the original trustees of the Peabody Institute, is elected president of the university’s board of trustees.

1873

March 10: In his letter to the trustees of The Johns Hopkins Hospital setting forth the principles they are to follow, Hopkins states that the hospital must provide for “The indigent sick of this city and its environs, without regard to sex, age, or color, who may require surgical or medical treatment, and who can be received into the Hospital without peril to other inmates.” Letter also directs that the hospital should accommodate four hundred patients, and that a school of nursing and a school of medicine should be established in conjunction with the hospital.

December 24: Johns Hopkins dies at his residence at 81 Saratoga Street in Baltimore at the age of 78. The funeral, conducted according to the form of the Society of Friends of which Mr. Hopkins was a member, is held December 26 from his home; he is buried in Greenmount Cemetery. (Read The Baltimore Sun obituary.) The Baltimore Sun estimates his estate at $8 million, including $2.25 million in stock of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company and $1 million in bank stock. In an editorial, the Suncompares Hopkins’ gift of the proposed university and hospital to those of George Peabody and Moses Sheppard and says of Hopkins, “It is gratifying to see a man who had thus successfully labored turning his attention ere life’s close to great schemes of beneficence, by which an undoubted good is to result which cannot be interred with his bones. The good which such men do lives after them, blossoming and bearing fruit for the improvement and happiness of future generations.”

1874

Peabody Academy of Music becomes the Peabody Conservatory of Music.

October: University trustees write to Daniel Coit Gilman, president of the University of California in Berkeley, requesting that he consider the presidency of Johns Hopkins. Gilman travels to Baltimore and meets with trustees on December 29 and tells them that he would create a major university devoted to research and scholarship. Trustees elect him president the following day.

1875

President Gilman begins his term as first president of The Johns Hopkins University. [Read Gilman’s inaugural address online.]

1876

February 12: At the annual meeting of the board of trustees of Peabody Institute, Judge George Brown makes the motion, which the trustees adopt, that “In view of the establishment of The Johns Hopkins University in our community, and of the wide field thus opened for the advancement of the intellectual & moral welfare of our people; and, desiring to establish, at the earliest date, affiliation with it in promoting the educational interests of the State: Resolved, That the Board of Trustees of The Peabody Institute convey to the President & Trustees of The Johns Hopkins University this expression of interest & good will; suggesting that this Institute being, within its scope, an educational element of the State, should be in sympathy with the university, and by interchanges of courtesy, and cooperation, assist in its high educational aims.”

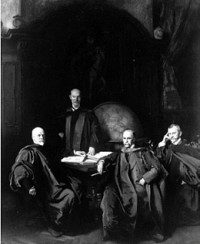

February 22: Daniel Coit Gilman is inaugurated as first president of The Johns Hopkins University during ceremonies at the Peabody Institute where the Peabody Orchestra performs. An editorial in the Gazette proclaims, “We consider this one of the most important events in the recent history of the city. Baltimore, which has so often been reproached as a big provincial town, is about to become the seat of a great university — a city set on a hill, a center of light.”

September 12: Thomas Huxley delivers the university’s opening address and sparks controversy among those who see his writing as subversive of religious faith.

October 4: First lecture at the new university given this day at 5 p.m. by Professor Basil Gildersleeve on Greek lyric poetry. Classes for students begin the next day. The faculty is composed of Gildersleeve (classics), James J. Sylvester (mathematics), Ira Remsen (chemistry), Henry A. Rowland (physics), and Henry Newell Martin (biology). [Learn more about Basil Gildersleeve online.]

1878

Professor James J. Sylvester edits the first issue of the American Journal of Mathematics, and it is published “under the auspices of” the Publication Agency of The Johns Hopkins University. The New York Times says, “Johns Hopkins University ought to become the highest court of appeal in theoretical science and philosophy. Looking to occupy a position of this kind, it is very appropriate that so important a step as the foundation of a journal of pure and applied mathematics should be taken by the Baltimore university.” [Learn more about James Sylvester online.]

Summer. Dr. William K. Brooks of the biology department opens a laboratory on the Chesapeake Bay, the first undertaking of its kind by a university and the first such laboratory south of New England. By 1880 The Johns Hopkins University Marine Zoological Laboratory has moved to Beaufort, North Carolina.

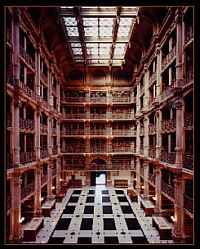

September 30: Peabody Library occupies a new building designed by Edmund G. Lind, who also designed the original building. The central well is sixty-one feet high, with six levels of stacks supported by cast-iron pillars. Fifteen percent of the library’s holdings are not duplicated in the Library of Congress.

1879

Professor Ira Remsen edits the first issue of the American Chemical Journal, which is published by the publication agency. [Learn more about Ira Remsen online.]

June: George W. McCreary, A. Chase Palmer, and Edward H. Spieker receive bachelor of arts degrees as the first graduates of The Johns Hopkins University.

1880

Basil L. Gildersleeve edits the first issue of the American Journal of Philology, which is published by the publication agency.

1881

April 22: Alexander Graham Bell lectures to a large audience in Hopkins Hall on his experiments with the transmission of sound by using rays of light instead of wires.

1882

June 3: First Peabody graduates receive their diplomas.

December: Herbert B. Adams, associate professor in history, edits Studies in Historical and Political Science, the first monograph series published by The Johns Hopkins University Publication Agency.

1883

January 30: In an address before the YMCA of Baltimore, John Work Garrett criticizes his fellow trustees for spending “enormous sums in the City of Baltimore and not at Clifton Park,” Johns Hopkins’ country estate where both men had expected the university to locate. Clifton is gradually whittled away by condemnation: in 1879 for a reservoir, in 1892 for a railroad right-of-way, and finally the remainder of the estate in 1895 for a public park. A close friend, neighbor, and colleague of Johns Hopkins, Mr. Garrett also takes issue on several occasions with the emphasis on graduate study and research which, he implies, prevents the university from doing much for the young men of the region, whom Mr. Hopkins had wanted to aid.

May 1: Druids Club of Baltimore defeats the newly formed Johns Hopkins lacrosse club 4-0. This is the last official game until 1888, when Hopkins enjoys its first win, a 6-2 victory over the Patterson Club. From 1888 Hopkins teams play every season except 1944, when athletics are curtailed by World War II.

December 3: The American notes, “Whenever there is a lecture at Johns Hopkins University upon a plain, everyday topic of practical importance, the audience consists almost exclusively of men; but when a speaker gets up to talk about abstruse psychological subjects, such as are discussed by Mr. Stanley Hall, there is always a large number of ladies present. The same singularity is noticed at the Peabody lectures when profound themes are elucidated.”

1884

The Johns Hopkins Glee Club gives its first concert. Woodrow Wilson sings first tenor. Wilson receives his Ph.D. in 1886; in 1913 he becomes the only U.S. president to hold an earned doctorate.

1885

May 4: University trustees adopt the official seal presented by Stephen Tucker of London. Tucker describes the seal as presenting “an heraldic picture of a University situated in the State founded by Lord Baltimore.” The seal carries the motto “Veritas vos Liberabit” (John 8:32) and the legend “The Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore: 1876.”

1886

Proficiency in Applied Electricity course to train students for engineering positions opens under the leadership of Louis Duncan. The course had been requested by local industry, especially the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The program is offered within the department of physics led by Henry A. Rowland, under whom Duncan had obtained his Ph.D. Duncan tells President Gilman that he sees the course as teaching “electricity as a science and in its practical application.” Course runs for thirteen years and certifies ninety-one students, almost all of whom become practicing electrical engineers.

April 26: A resolution is offered for formation of an alumni association at the observance of the tenth anniversary of the university at Mount Vernon Place Methodist Church.

1887

Kelly Miller, the first African-American student to enroll at Johns Hopkins University, begins his studies for a graduate degree in mathematics with the encouragement of Simon Newcomb, professor of mathematics. Miller is obliged to leave two years later when the university’s economic crisis prompts a twenty- five percent increase in tuition. Some years later, Newcomb and President Gilman recommend Miller for a faculty position at Howard University, his undergraduate alma mater, where he serves for many years as professor of mathematics and dean of arts and sciences.

1888

April 10: Hospital board learns that the hospital is completely finished inside and out except for the gas fixtures.

November 13: Daniel Coit Gilman and the Reverend J. F. Goucher give addresses at the opening ceremonies for the Woman’s College of Baltimore. The Sun deems it “one of the most comprehensive of its kind in the world, and a fit companion for the Johns Hopkins University.”

1889

May 7: About six hundred people attend ceremonies formally opening The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Mrs. Daniel Coit Gilman, writing to her daughters, describes the occasion: “Of course the great event of the week has been the opening of the hospital. The day was superb and all the buildings in apple pie order; grounds ditto. The exercises were in the administration building and a band of twenty- five instruments was in the third gallery. There was plenty of bunting and flowering plants and ladies in their gay dresses and it was a very pretty scene. Mr. Francis King made an excellent little address and Dr. Billings a very sensible one and Papa touched the popular heart as usual. I think all the speeches struck a very high note. There was no self-glorification, no mere spread eagle and empty oratory but a tone of earnest responsibility in the presence of a great trust. I think everyone must have been struck with it.”

September: Failure of Baltimore & Ohio Railroad stock creates a crisis in the university’s finances. Professors accept reduced salaries and fees are increased. President Gilman says 1889-90 school year will begin as usual.