Tumor Imaging Technique Tracks Responses to Cancer Therapies

Tumor Imaging Technique Tracks Responses to Cancer Therapies

Researchers have determined a new way to analyze MRI image data to assess blood vessels in cancer tumors. The technique may help identify patients who would benefit from certain therapies.

Cancer occurs when abnormal cells grow out of control. Tumors can develop a network of new blood vessels in a process known as angiogenesis. This network supplies the tumor with nutrients and oxygen, enabling the tumor to keep growing and spreading.

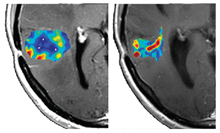

Vessel architectural imaging of a brain tumor before (left) and after (right) 28 days of drug therapy. Image by the researchers. Courtesy of Nature Medicine.

Tumor blood vessels can be leaky and have erratic microstructures. This is a problem because drugs designed to attack the tumor’s cancerous cells aren’t able to travel through the vessels to reach their targets. A class of drugs used to improve survival in cancer, known as anti-angiogenic agents, work by preventing new blood vessel growth. They also restore existing blood vessel structures to prevent leakage and improve the effectiveness of certain therapies.

The only ways to assess blood vessel architecture are to take a biopsy—a surgical procedure that can harm patients and often can’t be repeated—or PET scanning, which provides limited information and exposes patients to a dose of radiation.

To develop a better method, a team led by Drs. Kyrre Emblem and Gregory Sorensen of Massachusetts General Hospital examined data from MRI scans of tumors. This common technique is used to create detailed images of tissues in the body. Their work was funded in part by NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). Results appeared online on August 18, 2013, in Nature Medicine.

Taking advantage of a previously overlooked feature of MRI scans, the scientists developed and tested a new way of analyzing MRI data, which they termed vessel architectural imaging (VAI). VAI involves a single MRI exam that takes less than 2 minutes and, in most cases, can safely be repeated many times.

To assess the clinical relevance of VAI, the researchers examined MRI images from 30 people with recurrent glioblastomas—fast-growing brain tumors. The patients had been treated in a clinical trial with cediranib, an anti-angiogenesis drug.

Based on VAI analysis, the team identified 10 people who responded to the drug, as evidenced by features such as better microcirculation and structure of the tumor vessels. These responses might lead to better delivery of therapies and thus better outcomes. The researchers also identified 12 people who didn’t respond to the drug based on the MRI data.

When they compared the 2 groups, the researchers found that the median overall survival time for the responders was 341 days, compared to 146 days for nonresponders—about 6 months longer. These preliminary results suggest that VAI may one day be used to identify people in whom the anti-angiogenic drug therapy improves the structure and function of the microcirculation and thus their outcome.

“One of the biggest problems in cancer today is that we do not know who will benefit from a particular drug. Since only about half the patients who receive a typical anti-cancer drug benefit and the others just suffer side effects, knowing whether or not a patient’s tumor is responding to a drug can bring us one step closer to truly personalized medicine—tailoring therapies to the patients who will benefit and not wasting time and resources on treatments that will be ineffective,” Sorensen says.

By Carol Torgan, Ph.D.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.