Technique Directs Immune Cells to Target Leukemia

Technique Directs Immune Cells to Target Leukemia

A type of targeted immunotherapy induced remission in adults with an aggressive form of leukemia that had relapsed in 5 patients. The early results of this ongoing trial highlight the potential of the approach.

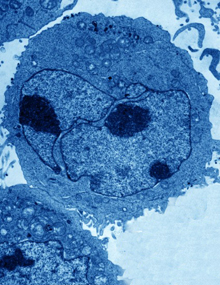

A lymphoblast, an abnormal cell occurring in lymphoblastic leukemia.Image by David Gregory and Debbie Marshall. All rights reserved by Wellcome Images.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. In patients with B-cell ALL, the marrow produces too many B lymphocytes, which make antibodies to help fight infection. When adult patients with B-cell ALL have remission followed by relapse, the prognosis is poor. Standard treatment uses chemotherapy to kill cancer cells, followed by a transplant of bone marrow stem cells to replace blood-forming cells destroyed by the chemotherapy.

Targeted immunotherapy has proven effective against less aggressive B-cell tumors. This technique directs the patient’s own immune system to attack cancer cells. The researchers first remove immune cells known as T cells from the patient. These cells are genetically modified to produce an artificial receptor that can latch onto B cells and trigger their destruction. The modified T cells are then infused back into the patient.

As the technique showed success in targeting other types of B-cell tumors, a team led by Drs. Michel Sadelain and Renier J. Brentjens at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center set out to test it in people with relapsed B-cell ALL. The receptor they added to the patients’ T cells was a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) designed to target a protein called CD19 found on the surface of B cells. Their phase I clinical trial was funded in part by NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI). Results appeared on March 20, 2013, inScience Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that all 5 of the patients who received the therapy were in complete remission within weeks of the CAR-modified T-cell infusion. Three patients were able to receive bone marrow transplants 1 to 4 months after the cell transfer therapy and were still in remission up to 2 years later. One patient was unable to receive a stem cell transplant after the targeted therapy and relapsed. Another died while in remission of complications likely unrelated to the therapy.

Overall, the therapy itself was well tolerated. Three of the patients developed fevers and 2 needed high-dose steroid therapy to treat inflammation triggered by the treatment.

“Patients with relapsed B-cell ALL resistant to chemotherapy have a particularly poor prognosis,” Brentjens says. “The ability of our approach to achieve complete remissions in all of these very sick patients is what makes these findings so remarkable and this novel therapy so promising.”

The researchers are now testing the CAR-modified T cells in several more patients. Further clinical trials have also been planned to test whether B-cell ALL patients would benefit from receiving this therapy earlier in the course of disease—either along with initial chemotherapy or during remission to help prevent relapse.

“We need to examine the effectiveness of this targeted immunotherapy in additional patients before it could potentially become a standard treatment for patients with relapsed B-cell ALL,” Brentjens says.

By Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.