Lab-Grown Kidneys Function in Rats

Lab-Grown Kidneys Function in Rats

Scientists have created artificial kidneys that can filter blood and produce urine when transplanted into rats. With further development, this approach could help the many patients who await organ transplants because their own kidneys no longer work.

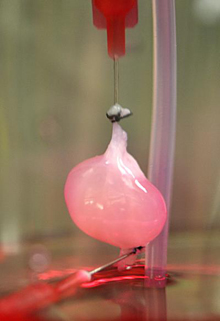

A decellularized rat kidney in a bioreactor after reseeding with endothelial cells. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine.

End-stage kidney disease, or renal failure, affects nearly 1 million people nationwide. Left untreated, it causes the body to retain excess water and waste products. Renal failure can be reversed by kidney transplants from well-matched donors. But about 1 in 5 recipients has problems with organ rejection within 5 years, and there aren’t enough donated kidneys to meet demand. About 100,000 people in the U.S. are now on the waiting list for a kidney transplant.

To provide new options for these patients, researchers have been exploring techniques for creating artificial kidneys and other organs. One promising approach uses detergents to delicately strip cells from organs, leaving behind a protein-based scaffold that wouldn’t be rejected by a recipient’s immune system. These decellularized organs are then seeded, or repopulated, with living cells. The method has been used by different research teams in efforts to create nonhuman bioengineered hearts, livers and lungs.

Dr. Harald C. Ott and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital created bioengineered kidneys by using a decellularization technology Ott had previously developed. Their research was funded in part by an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award and by NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The results were reported in the April 14, 2013, online edition of Nature Medicine.

The scientists first tested their approach by decellularizing kidneys from rats, pigs and human cadavers. They confirmed that the fine architecture of the kidneys remained intact, including the framework for tiny blood vessels and filtering systems.

To regenerate functional rat kidneys, the researchers mounted the decellularized organs within vacuum chambers to help draw new cells into the proper locations. Blood vessel linings were restored by delivering endothelial cells via the renal artery, which normally carries blood to the kidney. Remaining kidney tissues were populated by delivering newborn rat kidney cells via the ureter, which normally carries away urine.

The seeded scaffolds were then grown for several days in a nutrient-rich bioreactor. The reactor chamber mimicked conditions inside the body. The scientists showed that the resulting organs could perform kidney-like functions. The organs filtered fluids and generated urine in culture. When transplanted into rats, the artificial kidneys produced urine and successfully filtered out and reabsorbed certain molecules. But the regenerated kidneys didn’t work as well as normal kidney transplants.

Ott says the technique might be further improved by refining the cell types used for seeding and by changing the culture conditions. “Based on this initial proof of principle, we hope that bioengineered kidneys will someday be able to fully replace kidney function just as donor kidneys do,” says Ott. He and his colleagues are now developing techniques for creating human-sized organs.

By Vicki Contie

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.