Intestinal Mending Depends on Key Protein

Intestinal Mending Depends on Key Protein

Scientists identified a protein that’s essential for mending injuries to the intestinal lining in mice. The finding might have implications for understanding and repairing damage to the human intestinal wall, which can be caused by factors including inflammatory bowel disease, infection and irradiation.

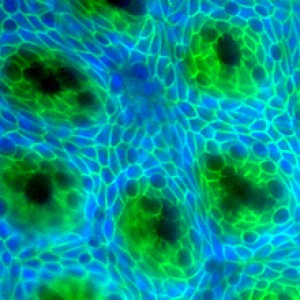

Crypts (dark green) are stem-cell-containing glands that help to regenerate the intestinal lining. Image by Hiroyuki Miyoshi, University of Washington in St. Louis.

The inner lining of the intestines is one of the most-often renewed surfaces in the human body, replenishing itself every 2 to 4 weeks. Lining replacement depends on stem cells stored within indentations called crypts, which are densely scattered across the intestine’s inner wall. When the lining is injured—for example, by infection or inflammation—crypts can be destroyed. Crypts can reappear, but their mechanism for renewal has been unclear.

In the new study, scientists led by Dr. Thaddeus S. Stappenbeck at Washington University in St. Louis took a closer look at the rejuvenation of intestinal crypts in mice. The research was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and National Cancer Institute (NCI). Their report appeared on October 5, 2012, in Science.

The scientists suspected that new crypts within wounds somehow arose from existing, nearby crypts. To test this idea, the scientists studied mice that had tiny injuries to the lining of the large intestine. The mice had initially lost up to about 300 crypts in the wounded areas. Within 4 days, the scientists found, a thin layer of slow-growing epithelial cells had emerged from nearby crypts and spread over the injured surface. Within 4 more days, an array of channels containing rapidly dividing stem cells had extended from the crypts into the wounded areas. The channels developed little cavities that eventually formed new crypts.

The researchers next wanted to identify the factors driving new crypt formation. They noted that cells adjacent to budding wound channels expressed high levels of Wnt genes. Wnt proteins are signaling molecules known to aid communication between cells. These proteins have been linked to embryo development, tissue regeneration and cancer. Wnt signaling is also known to play a role in intestinal development and to help control intestinal stem cells.

A closer analysis showed higher expression of the signaling molecule Wnt5a by certain cells in the wound bed. Wnt5a-producing cells, the researchers found, migrate from the outer surface of the intestine and collect near the wound. Further experiments showed that the Wnt5a protein slows the growth of stem cells within the wound channels, which in turn triggers the creation of new crypts.

To verify the role of Wnt5a in crypt formation, the scientists used specialized mice developed by NCI’s Dr. Terry Yamaguchi. The mice had been bred so that the Wnt5a gene could be switched off in specific tissues. When the gut lining was damaged and the gene turned off, wound channels formed as expected, but they did not create new crypts. The results suggest that Wnt5a is essential to crypt formation.

“Inflammatory bowel disease can destroy huge stretches of the lining, including the crypts,” says Stappenbeck. “It’s important to better understand how the crypts are replaced.” The scientists note that their findings might also be relevant to other Wnt-related processes, including hair follicle formation and cancer development.

By Vicki Contie

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.