Protein Creates Partition Between Bacteria and the Gut

Protein Creates Partition Between Bacteria and the Gut

Scientists have identified a microbe-fighting protein that helps create a buffer zone between the inner walls of the intestines and the bacteria within. The finding may explain how helpful bacteria can survive in the digestive tract without triggering an immune attack.

Researchers have long known that about 100 trillion bacteria reside in our intestines. Many of these microbes help us digest food and absorb important nutrients. In the colon, a dense layer of mucus creates a physical barrier between the gut’s walls and microbes. The mucus helps to prevent bacterial infection and an immune attack. However, in the small intestines, the mucus layer is thin and permeable to allow absorption of nutrients. Scientists have puzzled over how the mutually beneficial relationship between bacteria and host is maintained.

Researchers have long known that about 100 trillion bacteria reside in our intestines. Many of these microbes help us digest food and absorb important nutrients. In the colon, a dense layer of mucus creates a physical barrier between the gut’s walls and microbes. The mucus helps to prevent bacterial infection and an immune attack. However, in the small intestines, the mucus layer is thin and permeable to allow absorption of nutrients. Scientists have puzzled over how the mutually beneficial relationship between bacteria and host is maintained.

Dr. Lora Hooper of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and her colleagues suspected that certain immune mechanisms might work in partnership with the mucus layer in the small intestines to keep bacteria at bay. Their investigation, focusing on mice, was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

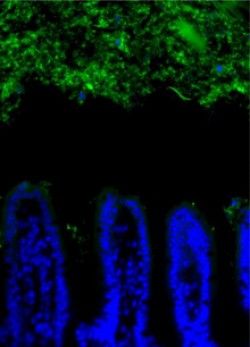

As reported in the October 14, 2011, issue of Science, the researchers first assessed how microbes are naturally positioned relative to the intestinal lining. Using a technique that makes bacteria glow green and intestinal walls blue, the scientists found a 50-micron zone of separation between the bacteria and the lining. Other researchers had previously found that the colon lining in mice also has a 50-micron bacteria-free zone.

The researchers then studied mice lacking the signaling protein MyD88, which activates the innate immune system. This branch of the immune system recognizes certain molecular patterns in disease-causing microbes. With the innate immune system impaired, bacteria invaded the protective zone and came in direct contact with the intestinal lining.

MyD88 controls the production of several antimicrobial proteins in specialized cells in the intestine’s lining. Following this clue, the researchers identified a protein called RegIIIγ as responsible for the bacteria-free zone. Mice lacking RegIIIγ lacked the buffer zone between bacteria and the intestinal wall. The intestinal lining had increased numbers of bacteria adhering to it—a feature sometimes seen with digestive disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease.

“Maintaining a protective zone between you and your bacteria seems to be important for maintaining intestinal health,” says Hooper. “Our research shows that RegIIIγ is critical for maintaining what we call the demilitarized zone—the zone of separation between the surface of the intestine and the bulk of bacteria.” RegIIIγ and related proteins might represent a potential new target for treating or preventing certain digestive disorders.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.