Gut Microbes May Affect Cancer Treatment

Gut Microbes May Affect Cancer Treatment

The effectiveness of certain cancer therapies may depend on microbes that live in the intestine, according to a study in mice. The findings suggest that antibiotics used to treat infections might hinder the effects of anti-cancer therapies.

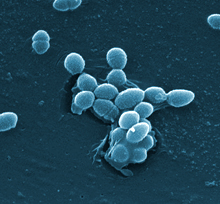

The bacterium Enterococcus faecalis, which lives in the human gut. Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The human gut harbors a complex community of microbes, collectively called microbiota. Recent research has revealed many aspects of our health that are affected by intestinal microbiota. For instance, gut microbes can influence both local and body-wide immune system activity and inflammation.

Some cancer therapies work by stimulating anti-cancer immune responses. To investigate whether gut microbes can affect cancer treatments, scientists at NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) studied germ-free mice, raised in sterile conditions from birth. These mice harbor no bacteria. The team also studied conventionally raised mice given a potent antibiotic cocktail in their drinking water beginning 3 weeks prior to the experiments.

Lymphoma, colon, and melanoma cancer cells were injected under the skin of the mice. The cells formed tumors that grew to a diameter of one-fifth of an inch or more. The tumors were then treated with either an immunotherapy that included CpG-oligonucleotides or with the mainstay chemotherapy drugs oxaliplatin and cisplatin. The immunotherapy stimulates an immune attack on cancer cells, whereas the chemotherapy drugs directly damage tumors. The study, led by Drs. Romina Goldszmid and Giorgio Trinchieri of NCI, appeared on November 22, 2013, in Science.

The researchers found that tumors responded poorly to the immunotherapy in both germ-free mice and mice that received the antibiotic cocktail. The tumors in these mice also responded poorly to oxaliplatin and cisplatin. Further research showed that the mice produced lower levels of immune signaling molecules called cytokines after treatment than control mice. The germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice also had reduced expression of genes involved in inflammation.

In a related study that appeared in the same issue of Science, a team led by Dr. Laurence Zitvogel of the Gustave Roussy Institute in Paris showed that the gut microbiota helps to shape the immune response to a different type of chemotherapy drug, cyclophosphamide.

“The use of antibiotics should be considered as an important element affecting microbiota composition. It has been demonstrated, and our present study has confirmed, that after antibiotic treatment the bacterial composition in the gut never returns to its initial composition,” Trinchieri says. “Thus, our findings raise the possibility that the frequent use of antibiotics during a patient’s lifetime or to treat infections related to cancer and its side effects may affect the success of anti-cancer therapy.”

The researchers now plan to study how antibiotics and gut bacteria might affect tumor therapy in people. They will also continue studying mice to characterize the molecular signaling between gut microbes and the immune system.

![]()

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.