Social learning in a medical photo-sharing app for doctors

Social learning in a medical photo-sharing app for doctors

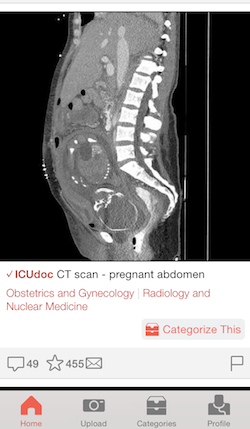

Figure 1, a free medical photo-sharing app for health-care professionals, has been likened to Instagram for its social functions of posting, favoriting and commenting on photos. It’s also a useful learning tool. Co-founder Joshua Landy, MD, a Toronto-based critical care physician, had an idea to expand the reach of the “teachable moments” he and his fellow ICU physicians would photograph on the job and exchange among themselves. Technical co-founder Richard Penner, a software developer, ensured a smooth user experience as well as a face-blocking algorithm. (All identifying information about a patient must be removed or blurred from photos, and content providers sign a quick, HIPAA-compliant consent form for each photo uploaded.)

Last summer, Landy spent time at Stanford as a visiting scholar, working with anesthesiologist Alex Macario, MD, on mobile-health research and online tools for medical education. He answered questions about their work together and his vision for Figure 1; his responses appear below.

What needs of your practice did you fill with Figure 1′s medical photo-sharing and collaboration abilities? Or the practices of your colleagues?

Figure 1 has been a useful resource to me for expanding the number of cases I’ve seen in my practice. It’s also been a great place for me to share a lot the moments I’ve learned from.

One of the unexpected benefits of Figure 1 for me is that it takes the sometimes lonely practice of medicine and makes it a more communal experience. At any time, I know that I can connect with people in similar circumstances who are focused on solving similar problems in healthcare.

What was the nature of your mobile-health research with Dr. Macario?

We researched online approaches to medical education, resulting in several articles describing new trends in the field, including a new trend of delivering curricular content online from home and converting class time to tutorial sessions with a professor (known as the flipped classroom). Our group also conducted a survey of mobile device use in medical students and residents.

What did those survey results show?

One conclusion we reached was that different specialties have different content and application needs when it comes to smart device apps. Some physicians, like neurologists, will use photo-sharing and text messages to communicate; others, like internists, will use reference apps to look up drug doses and side effects; some surgeons use anatomy teaching apps to help educate patients.

This particular study was meant to present the perspectives of the residents, giving a voice to the health-care professionals that are on the front lines of patient care. Seeing the native behaviours that evolve among trainees permits us to learn about what new tools may be needed, and which of these tools are likely to be accepted or rejected. We found that 60 percent of our physicians were exchanging patient care-related photos and text messages, and 45 percent acknowledged using their device “as a medical reference, textbook, or as a patient care related study aid.”

How do you think Figure 1 could contribute to medical education?

Growing your skill set as a medical practitioner is directly related to the number of cases you see. Seeing more cases, even in a lightweight format, will hopefully drive medical curiosity and influence learners to study real-life cases. Additionally, having another professional to interact with at the other end of the case provides a vibrant learning experience.

Figure 1 users can search by anatomy or within specialties. I was surprised that palliative medicine and psychiatry, which seem more challenging to capture in photos than something like orthopedic surgery, were included among the disciplines. What do you hope to include down the line?

When we started Figure 1, we had some ideas about which specialties would lend themselves well to being photographed. Psychiatry, as you mentioned, is a category where one might not expect many visual findings. To our surprise, we are seeing that innovative users are finding visual manifestations of mental illness and many other diseases too. These images help one appreciate the more subtle, human aspects of disease.

In the future, I think it would be great to introduce more photos showing what happens under the microscope. So much of medicine happens on a smaller scale than we appreciate. It would also be great to include toxicology or more laboratory based categories. Ultimately, we have a mandate to document the entirety of medicine and its visual representations, so there are likely to be many more categories added.

Are there any conditions you could consider inappropriate to photograph?

A health-care professional’s duty is to treat their patients with respect and empathy. I think almost anything can be photographed if it’s done with patient privacy in mind, and in the interest of helping other healthcare professionals and their patients. If the image would help somebody else in a similar experience, then I think it’s an appropriate and beneficial medical image.

.

By Emily Hite

Stanford University Medical Center

###

* Stanford University Medical Center integrates research, medical education and patient care at its three institutions – Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

** The above story is adapted from materials provided by Stanford University School of Medicine

________________________________________________________________