Researchers Pinpoint Origin of Deadly Brain Tumor

Researchers Pinpoint Origin of Deadly Brain Tumor

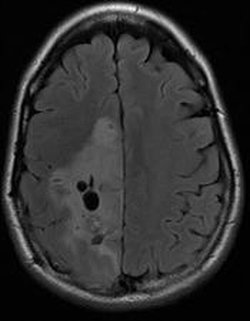

An oligodendroglioma is visible in the large area that appears slightly lighter, on the left side of the image.

Scientists have identified the type of cell that is at the origin of brain tumors known as oligodendrogliomas, which are a type of glioma – a category that defines the most common type of malignant brain tumor.

In a paper published in the December 2010 issue of the journal Cancer Cell, investigators found that the tumor originates in and spreads through cells known as glial progenitor cells – cells that are often referred to as “daughter” cells of stem cells. The work comes at a time when many researchers are actively investigating the role that stem cells which have gone awry play in causing cancer. For scientists trying to create new ways to treat brain tumors, knowing whether stem cells or progenitor cells are part of the process is crucial.

“In many ways progenitor cells are controlled by completely different signaling pathways than true stem cells,” said Steven Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., a University of Rochester neurologist who was part of the study team. “Knowing which type of cell is involved gives us a clear look at what drug approaches might be useful to try to stop these tumors. Comparing normal progenitor cells to progenitors that give rise to tumors gives us a roadmap to follow as we try to develop new treatments.”

The study was the product of a multi-institutional collaboration led by William Weiss, M.D., Ph.D., a neuro-oncologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

The study focuses on oligodendrogliomas, a type of tumor that presents with symptoms much like other brain tumors – headaches, seizures, and cognitive changes. The tumors are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Oligodendrogliomas at first are less deadly and invasive than most other gliomas. Unfortunately, treatments like surgery typically slow or stop the tumor initially, but it usually returns, often in a much more aggressive form than it was to begin with. The majority of patients with oligodendrogliomas ultimately die from the disease.

In order to identify better treatments for this tumor, researchers need to know what cell type in the brain gives rise to it. Despite abundant clinical experience with this type of cancer, no one had ever defined oligodendroglioma’s cell of origin. To answer this question, the team used a common brain tumor drug, temozolomide, to test several types of cells from both human and mouse tumors. They found that the drug was effective against oligodendroglioma cells and normal glial progenitor cells, and much less effective against either brain stem cells or other brain tumors called astrocytomas.

The work is the latest in a string of findings that progenitor cells are the origin for some brain tumors. Four years ago, Goldman’s team pinpointed a progenitor cell as the origin of a brain tumor known as a neurocytoma. Separately, other scientists have found that brain tumors called medulloblastomas and ependymomas also arise from progenitor cells.

“Right now, when treating most brain tumor patients, one size fits all,” said Goldman, chair of the Department of Neurology and head of the laboratory where much of the genetic analysis for the study was done. “As with many forms of cancer, today’s treatments of glioma are not very specific – they take aim at all dividing cells. Unfortunately, with brain tumors, it’s often the most aggressive, malignant cells that survive chemotherapy and radiation, and they take over the tumor and ultimately kill the patient.

“As with any type of cancer, the hope ultimately is to create treatments that target cancer cells while leaving healthy cells intact. That’s where our current work – searching for differences between normal progenitor cells and cancer progenitor cells – fits in,” added Goldman.

An Enhanced Brain Tumor Program in Rochester

The basic research on brain tumors, with findings that could affect treatment decisions for patients worldwide, is the type of work that was hard to find at the University of Rochester Medical Center just a decade ago.

In the past few years, the University’s Program for Brain and Spinal Tumors has been enhanced dramatically. Through the James P. Wilmot Cancer Center, about 100 patients with primary brain tumors are treated each year. The program includes physicians and scientists from several departments or units, including Neurosurgery, Neurology, Pediatrics, Endocrinology/Metabolism, and Radiation Oncology, as well as the Wilmot Cancer Center.

Clinically, among the new arrivals are neurologist Nimish Mohile, M.D., who completed a fellowship in neuro-oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering; neurosurgeon Kevin Walter, M.D., and researcher Eleanor Carson-Walter, Ph.D., who had previously been at both Johns Hopkins and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; neurosurgeon Edward Vates, M.D., Ph.D., recruited from UCSF; and physician assistant Jennifer Serventi, RPA-C, who previously worked with brain tumor patients at New York Presbyterian Hospital.

The Department of Neurology has also recently established a neuro-oncology fellowship, under the direction of Goldman and Mohile, that attracts and provides further training to some of the most promising brain tumor specialists in the nation. In addition, Rochester is now part of the national Oligodendroglioma Study Group, which does clinical studies in people with that type of tumor.

On the laboratory side, research on brain tumors is underway in a suite of labs that did not exist at the Medical Center a decade ago, including labs run by Goldman, Maiken Nedergaard, M.D., D.M.Sc., Walter and Carson-Walter, and Romane Auvergne, Ph.D., all in the Center for Translational Neuromedicine, and Mark Noble, Ph.D., in Biomedical Genetics.

Other University of Rochester authors of the latest paper include Auvergne, a senior instructor in Neurology, and Fraser Sim, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Neurology, who recently established his own laboratory at the University of Buffalo. In addition, UCSF scientist Anders I. Persson, Ph.D., was first author of the study, which included several additional UCSF scientists. Akiko Nishiyama from the University of Connecticut and William B. Stallcup, Ph.D., from Burnham Institute for Medical Research in La Jolla, Calif., also took part in the study.

Rochester’s portion of the study was supported by the New York State Stem Cell Science Board, the Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the James S. McDonnell Foundation.

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by University of Rochester Medical Center