Potential therapeutic target for Huntington’s disease discovered by researchers in Taiwan, Stanford

Potential therapeutic target for Huntington’s disease discovered by researchers in Taiwan, Stanford

Huntington’s disease is a progressive, fatal neurological disorder with no cure. But now researchers at the National Yang-Ming University in Taiwan and Stanford’s School of Medicine have discovered a protein that may one day be a viable therapeutic target for those afflicted with the condition. According to co-senior author Tzu-Hao Cheng, PhD, associate professor at National Yang-Ming University’s Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology:

Huntington’s disease is a devastating disease with no cure available at this time. Targeting the transcription factor identified in our research may one day be able to prevent or delay the formation of the protein aggregates that are the hallmark of this and other neurodegenerative diseases. We are hopeful that our studies will be a major advance in the field.

The research will be published tomorrow in the journal Cell. It was a joint collaboration between Cheng’s laboratory and that of Stanley N. Cohen, MD, professor of genetics here at Stanford. The findings are exciting because they suggest there may be a way to prevent the tangled clumps of huntingtin protein that cause the disorder.

About one in 10,000 people of western European descent have Huntington’s disease, which is particularly heartbreaking because of the slow but inevitable decline in sufferers’ physical and mental capacity. The disorder is characterized by uncontrollable movements, mental deterioration and eventual dementia. It’s genetic, and a child of an affected parent has a 50 percent chance of also developing the condition.

The advent of genetic testing has allowed people to know whether they carry the gene years before symptoms begin (usually in mid-life), but the lack of a cure or any kind of treatment has sparked discussion as to the utility of early diagnosis.

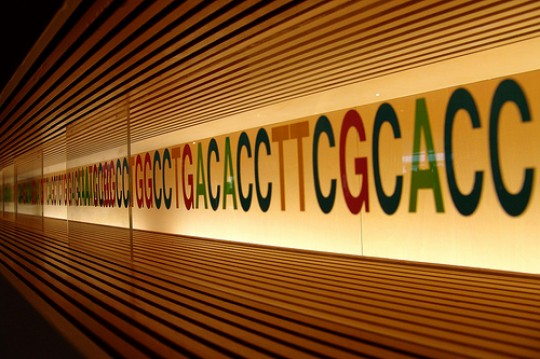

People with the condition have long stretches of repeats of the same three nucleotides in their huntingtin gene. Unaffected people have between eight and twenty-five repeats of the nucleotides cytosine, adenine and guanine, or CAG; the genes of affected people have 36 or more of these genetic stutters. As a result, the mutant protein has an extended region of glutamine, which is sticky and binds to itself and to similar regions in other huntingtin protein molecules to create clumps of useless protein that can severely damage nerve cells and lead to the disease.

In the current study, the researchers identified a molecule in yeast called Spt4 (or Supt4h in mammals) necessary to transcribe the huntingtin gene into protein. Interfering with the function of Supt4h reduces the amount of huntingtin protein in mouse cells that mimic the disease, as well as the number of protein clumps. Although any human trials are far off, there are intriguing glimpses of a pathway to possible therapy. According to the study:

Together these observations argue that agents targeting Supt4h may reduce the transcription of genes containing lengthy trinucleotide repeats while having limited effects on normal mammalian cell function.

By Krista Conger

Stanford University Medical Center

Photo by MJ/TR

###

* Stanford University Medical Center integrates research, medical education and patient care at its three institutions – Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

** The above story is adapted from materials provided by Stanford University School of Medicine

________________________________________________________________