Nursing home closures concentrated in poorest areas

Nursing home closures concentrated in poorest areas

A nationwide study of nursing home closures finds that the country has lost 5 percent of its beds, and that closures are twice as likely in the poorest areas than in the richest areas. Researchers say this will mean less access to nursing home care for the people – particularly minorities – who still depend on it.

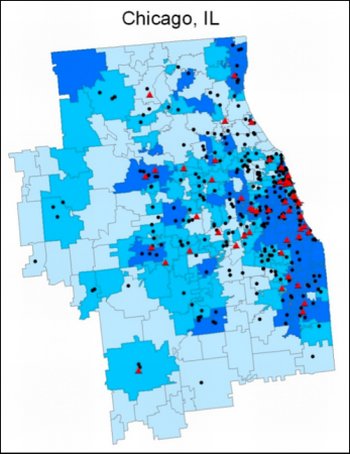

Fewer options for the needy Nursing home closures (red triangles) in the Chicago area overlap closely with the poorest third of ZIP codes (darkest blue). Black dots represent nursing homes still open. Credit: Zhanlian Feng/Brown University

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — While wealthier people have chosen alternatives to urban nursing homes, the urban poor still depend on them for long-term care. A new study led by researchers at Brown University finds that option is nevertheless slipping away. Between 1999 and 2008, nursing home closures in the United States were concentrated disproportionately in poor, urban and predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Overall, the United States lost 5 percent, or 96,902, of its total nursing home beds during the decade, as patients with means sought assisted living or other forms of home and community-based care instead. But nonhospital nursing homes were twice as likely to close in the poorest ZIP codes of the country than in the richest ones, the researchers report January 10 in Archives of Internal Medicine. Nursing homes were also 1.38 times more likely to close in the most predominantly black ZIP codes than in ZIP codes with the lowest representation of blacks, and 1.37 times as likely to close in the most predominantly Hispanic ZIP codes than in the least Hispanic areas.

Battered by a change in Medicare payment policy in 1998, the nation’s count of hospital-based nursing homes declined by 50 percent between 1999 and 2008, also closing disproportionately in predominantly black and Hispanic, but not necessarily poorer, areas.

The net result is that poor and urban people, particularly minorities, will have fewer choices for the long-term care they need, said Vince Mor, the Florence Pirce Grant University Professor of Community Health at Brown and a senior author of the paper.

“This is an issue that is not going to go away, precisely because of the aging of the population and the increasing bifurcation of society into rich and poor,” he said.

The researchers, led by Zhanlian Feng, assistant professor of community Health and first author of the paper, also found that many people in poor urban neighborhoods will have to travel significantly farther to a nursing home. In ZIP codes where at least one nursing home closed during the decade, the shortest distance to another home increased to 3.81 miles from 2.73 miles.

“The further the patient is from their neighborhood, the more difficult it is for their family members and their neighbors to come visit them,” Mor said.

The moral dilemma

In the study period, most nursing homes, whether freestanding or on hospital campuses, in rich neighborhoods and poor ones, have become more economically vulnerable, the researchers said. Homes that depend on Medicare and Medicaid for most or all of their revenue – for instance those serving poor patients — have suffered the most pressure.

When money becomes tight, especially at a somewhat inefficiently run home, quality of care declines, sometimes to the point where officials must consider shutting it down.

“This leads to a moral dilemma,” Mor said. “If the local nursing home is closed because their quality is so poor, that’s good, but the cost of that closure is disproportionately borne by a community. How much do you invest in a failing facility and how do you make that investment without rewarding a bad actor who runs a lousy place?”

If finding new money for nursing homes is not the entire answer for preserving access for the poor to long-term care, another option is to shift more money toward alternatives like assisted living, home-based care and community-based care, Mor said. The new health care law and a system of waivers within Medicaid encourage states to do just that, but they are not targeted specifically to helping the urban poor or minorities, and they are optional programs. By contrast, reimbursements for nursing home care are legally required.

“Given the current budget environment, it is really uncertain how sustainable these alternatives will be,” Feng said.

Polls have shown that people only go to nursing homes when they have no other choice. “Nursing homes are generally perceived as a last resort,” Feng said.

The new study shows that for millions of Americans there are now fewer desirable options within that undesired choice.

The paper’s authors are Brown researchers Michael Lepore, Melissa Clark, Denise Tyler, and Mary Fennell, and Drexel University researcher David Smith.

The study was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging.

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by Brown University

** More information at Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island, USA)