Neighbors Help Cancer Cells Resist Treatment

Neighbors Help Cancer Cells Resist Treatment

A new study shows that surrounding cells can help tumors develop resistance to drugs. The finding may change the way researchers approach the treatment of many cancers.

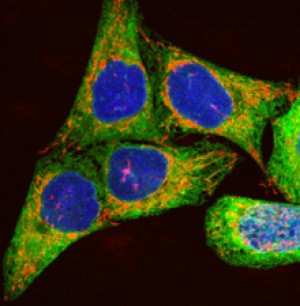

Human melanoma cells growing in culture. Image by Paul J.Smith & Rachel Errington, Wellcome Images. All rights reserved by Wellcome Images.

Drugs designed to target unique tumor proteins hold great promise for cancer treatment. However, many tumors become resistant to treatment over time. For example, deadly skin cancers called melanomas often harbor a mutant form of a gene known as BRAF.Although these particular tumors initially respond well to a class of drugs called RAF inhibitors, in many cases the treatment is only partly successful, and the tumors later recur within 6 months.

A research team led by Dr. Todd Golub at the Broad Institute and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute set out to explore factors in the tumor’s environment that might play a role in drug resistance. They developed a co-culture system in which tumor cells are grown in the laboratory along with stromal cells—cells from the tissue that surrounds tumors. They then tested the ability of the stromal cells to affect drug sensitivity.

The researchers cultured 45 human cancer cell lines either alone or in combination with a panel of about 2 dozen human stromal cell lines. They then tested increasing doses of 35 widely used anticancer drugs, including 23 targeted drugs. Their work was funded partly by NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI). Results appeared in the early online edition of Nature on July 4, 2012.

The scientists found that anticancer drugs were often less effective when the tumor cells were cultured along with stromal cells. Significantly, stromal cells led to increased resistance to 15 of the 23 targeted drugs (65%).

The team next explored how stromal cells affected tumor resistance to a RAF inhibitor called PLX4720. A similar compound, vemurafenib, was recently approved by the FDA for treating BRAF-mutant melanoma. By testing the growth media of the stromal cells, the scientists discovered that the cells released a compound called hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which helped the tumor cells become resistant. Further experiments revealed the pathway that allowed the tumor cells to resist the RAF inhibitor. Among their findings was that HGF activated a tumor cell receptor called MET.

The researchers asked whether HGF plays a role in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma. They examined biopsy samples obtained immediately before treatment and found HGF in stromal cells from 23 of 34 patients (68%). They also found that patients whose stromal cells secreted HGF had a significantly poorer response to treatment.

The scientists uncovered a similar resistance mechanism in BRAF-mutant colorectal and glioblastoma cell lines. They also discovered that they could reverse drug resistance in the BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines by inhibiting RAF plus either HGF or MET. This finding suggests a potential therapeutic strategy. The researchers note that several inhibitors of HGF or MET are currently in clinical development.

“Historically, researchers would go to great lengths to pluck out tumor cells from a sample and discard the rest of the tissue,” Golub says. “But what we’re finding now is that those non-tumor cells that make up the microenvironment may be an important source of drug resistance.”

By Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.