Manganese May Prevent Toxin Damage

Manganese May Prevent Toxin Damage

A new study suggests that manganese, an essential nutrient, may prevent the deadly effects of Shiga toxin. The finding may lead to cheap, effective treatments for dangerous foodborne Shigella or E. coli infections, which currently affect millions worldwide.

Foodborne illness is often caused by bacteria that contaminate raw foods. To healthy people, most of these bacteria are harmless. Infections by bacterial strains that carry Shiga toxin, however, can lead to dangerous complications, including severe bloody diarrhea, kidney failure and even death. Shiga toxin is a protein produced by certain strains of Shigella and E. coli bacteria. When cells of the digestive tract take up Shiga toxin, it interferes with cellular functions and the cells die.

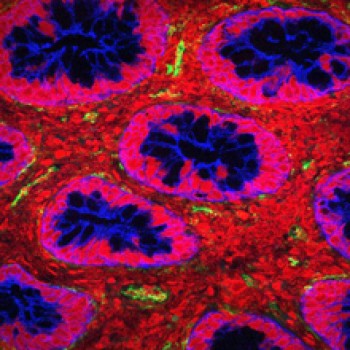

Ordinarily, dangerous proteins taken up by the cell are routed via a compartment called the endosome to the lysosome, where they’re destroyed. Shiga toxin, however, escapes this route by leaving the endosome and traveling through the Golgi apparatus to the cell’s protein production machinery. Once there, the toxin halts protein production and kills the cell.

In earlier research, scientists directed by Dr. Adam Linstedt of Carnegie Mellon University found that Shiga toxin uses a specific cellular protein, called GPP130, to bypass the cell’s defenses and avoid destruction. GPP130 ordinarily moves between the endosome and the Golgi apparatus. However, manganese disrupts this movement and causes the cell to break down GPP130. Linstedt and his colleagues reasoned that because manganese could divert GPP130, it might also affect Shiga toxin. Their work, funded by NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), appeared in the January 20, 2012, issue of Science.

Curious about the connection between GPP130 and Shiga toxin, the researchers broke the GPP130 protein into pieces. They found that Shiga toxin binds directly to one section of the GPP130 protein. This binding allows Shiga toxin to avoid destruction in the lysosome by piggybacking a ride on GPP130 as it leaves the endosome to travel to the Golgi.

When the scientists added manganese to the mix, GPP130 was destroyed by the cell. Without GPP130, Shiga toxin couldn’t escape from the endosome and instead moved to lysosomes for destruction.

The researchers next pretreated mice with several doses of manganese, and then gave the mice lethal doses of Shiga toxin. All the mice without pretreatment died within 4 days. All those pretreated with higher doses of manganese survived. This pretreatment experiment may not directly translate to clinical use. However, with further research, the scientists hope to find a manganese treatment that can be used as a preventative measure or at disease onset to prevent Shiga toxin-related death.

“While Shiga toxin infection affects people in the developed world, it affects far more people in the developing world. An inexpensive, accessible treatment—not a designer drug—is the ideal solution,” says Linstedt.

These findings point toward an inexpensive, life-saving treatment for millions worldwide. However, because excess manganese can cause serious side effects, more work must be done to determine if manganese can be safe and effective for use in humans.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.