New Insights Into Old Anti-Fungal Drug

New Insights Into Old Anti-Fungal Drug

For more than 50 years, doctors have used the drug Amphotericin B (AmB) to treat systemic fungal infections. In a new study, researchers revealed a novel mode of action for the drug. Their findings could lead to safer and more effective anti-fungal medications.

For people with compromised immune systems—such as those with AIDS or who need to take immunosuppressive drugs—common environmental fungi can become a deadly hazard. Fungal cells like yeasts and molds can invade the body and create a systemic infection. To treat this condition, doctors sometimes prescribe AmB, which is a powerful anti-fungal molecule that was isolated from bacteria in the 1950s. Unfortunately, AmB is also highly toxic to humans, so it is used only as a last resort.

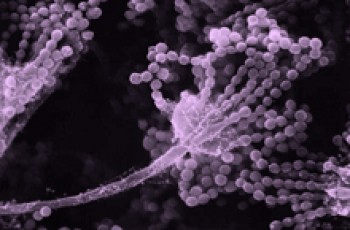

Scanning electron micrograph of the fungus Aspergillus.

Image by Janice Haney Carr, CDC.

For many years, scientists believed that AmB kills fungi by opening a hole, or channel, in the fungal cell membrane, allowing electrically charged molecules (ions) to flow out. A group of scientists led by Dr. Martin Burke at the University of Illinois thought that AmB might be killing fungal cells by another mechanism. In a previous study, the team found that AmB initially binds a molecule called ergosterol on the outer membrane of fungal cells. Ergosterol is essentially the fungal equivalent of cholesterol and is vital for fungal cell survival. AmB derivatives that don’t bind ergosterol don’t form ion channels and have no antifungal activity.

To find out which mechanism—the ergosterol binding itself or the subsequent channel formation—kills the fungi, the researchers created AmB-like compounds that could bind ergosterol without forming channels. Their work, funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), appeared in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on January 17, 2012.

The researchers began by comparing AmB to a similar fungicide called natamycin. Natamycin was recently found to bind ergosterol. However, it doesn’t form ion channels. The scientists noted that both molecules shared a similar ergosterol binding arm, but that AmB alone had an element required for channel formation. Using a chemical synthesis technique the scientists recently developed, they created a new form of AmB without the channel-forming element, called C35deOAmB.

The scientists performed a series of comparisons of AmB, C35deOAmB and natamycin. They found that while all 3 could bind to ergosterol and all 3 could kill yeast cells, only AmB formed channels and allowed ions to escape.

“The results are all consistent with the same conclusion,” Burke says. “In contrast to half a century of prior study and the textbook-classic model, amphotericin kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol.”

A better understanding of how AmB kills fungi could help scientists design better anti-fungal drugs. Because AmB binds both ergosterol and cholesterol, the researchers are currently working to develop similar drugs that bind only ergosterol. They believe this might limit the toxic side effects while still preserving anti-fungal activity.

“When I was in my medical rotations, we called it ‘ampho-terrible,’ because it’s an awful medicine for patients,” Burke says. “Now we have a road map to take ampho-terrible and turn it into ampho-terrific.”

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.