Infection Makes Mosquitoes Immune to Malaria Parasites

Infection Makes Mosquitoes Immune to Malaria Parasites

Researchers established a bacterial infection in mosquitoes that helps fight the parasites that cause malaria. The infected insects could be a significant tool for malaria control.

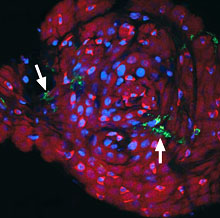

Wolbachia (green, indicated by white arrows) in an infected mosquito’s midgut. Image by the Xi lab, used courtesy of Science.

Malaria is caused by a single-cell parasite called Plasmodium. The parasite infects female mosquitoes when they feed on the blood of an infected person. Once in the mosquito’s midgut, the parasites multiply and migrate to the salivary glands, ready to infect a new person when the mosquito next bites.

Malaria remains one of the most common infectious diseases in the world. It kills hundreds of thousands each year, mostly young children in sub-Saharan Africa. Treating bed nets and indoor walls with insecticides is the main prevention strategy in developing countries. However, the mosquitoes that transmit malaria are slowly becoming resistant to these chemicals, creating an urgent need for new approaches.

Wolbachia is a naturally occurring bacterium that was previously found to block development of Plasmodium parasites in mosquitoes. Wolbachia can be transmitted by an infected female insect to her offspring. Uninfected females that mate with infected males rarely produce viable eggs—a reproductive dead end that gives infected females a reproductive advantage and helps the bacteria spread quickly. Wolbachia were successfully used in a field trial to control dengue, another mosquito-borne disease. However, the bacteria don’t pass consistently from a mother to her offspring in Anopheles mosquitoes, which spread malaria.

A team led by Dr. Zhiyong Xi at Michigan State University set out to establish a stable, inherited Wolbachia infection that could blockPlasmodium growth in Anopheles. They focused on Anopheles stephensi, the primary malaria carrier in the Middle East and South Asia. Their work was funded in part by NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Results appeared on May 10, 2013, in Science.

The researchers injected a strain of Wolbachia derived from another type of mosquito into A. stephensi embryos. Once matured, the adult females mated with uninfected male mosquitoes to create a stable Wolbachiainfection that persisted for 34 generations (the end of the study period). Uninfected females rarely produced viable eggs with infected males.

To see how well the infected mosquitoes could invade an uninfected A. stephensi population, the researchers tested groups of insects in the laboratory. When infected females comprised as little as 5% of the population, all the mosquitoes became infected with Wolbachia within 8 generations.

The researchers found that Wolbachia infection reduced the number of malaria parasites in both the mosquito midgut and salivary glands. They hypothesize that Wolbachia infection causes the formation of unstable compounds known as reactive oxygen species, which inhibit parasite development.

This study highlights the potential of using Wolbachia in malaria control. “Wolbachia-based malaria control strategy has been discussed for the last 2 decades,” Xi says. “Our work is the first to demonstrate Wolbachia can be stably established in a key malaria vector, the mosquito species Anopheles stephensi, which opens the door to use Wolbachia for malaria control.”

By Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.