Gene Therapy for Salivary Gland Shows Promise

Gene Therapy for Salivary Gland Shows Promise

An experimental trial showed that gene therapy can be performed safely in the human salivary gland. The accomplishment may one day lead to treatments to help head and neck cancer survivors who battle with chronic dry mouth.

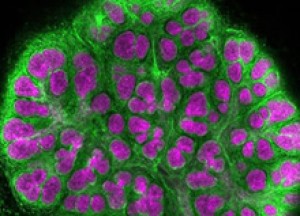

A mouse embryonic salivary gland.Credit: Melinda Larsen et al., Developmental Biology 255: 178-191, 2003.

People with head and neck cancer often receive radiation therapy to shrink their tumors. The radiation can damage salivary glands, reducing their ability to secrete saliva into the mouth. Saliva is needed for taste, swallowing and speech. It also helps prevent infection and tooth decay. Salivary glands may partly recover after radiation therapy, but recovery is usually not complete. Doctors have limited options to offer most patients.

In the early 1990s, as the first gene therapy studies entered research clinics, Dr. Bruce Baum of NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) saw the potential of gene therapy to restore saliva secretion in salivary glands. He and his colleagues have been working for years to restore saliva secretion in animal models. By delivering the gene for a protein called aquaporin-1 into salivary gland cells, they restored saliva secretion in animal models. Aquaporin-1 forms pore-like water channels in cell membranes to help move fluid—such as when salivary gland cells secrete saliva into the mouth.

In 2008, the scientists treated the first patients in a small clinical trial designed to assess safety, work out dosage and identify side effects. The team included investigators from NIDCR, NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the NIH Clinical Center.

Eleven head and neck cancer survivors received a single-dose infusion directly into one of their 2 parotid salivary glands, the largest of the major salivary glands. The aquaporin-1 gene was packaged in a disabled adenovirus, which causes the common cold when intact. The disabled virus served as a delivery vehicle, or vector, entering cells that line the salivary gland and transferring the gene within. Once inside, the gene is turned on, or expressed, and directs the cells to make aquaporin-1.

The scientists reported on November 20, 2012, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that 6 of the 11 treated participants had increased levels of saliva secretion. Five also reported a renewed sense of moisture and lubrication in their mouths over the initial 42-day study period. There were no serious side effects.

The researchers tested 4 different doses of virus in the trial. Neither of the 2 people receiving the highest dose showed any benefit from the procedure. This and other observations suggest that higher doses of this virus may backfire, causing the immune system to launch an attack and prevent gene transfer.

“It is time to evaluate a different vector to deliver the aquaporin-1 gene, one that will cause only a minimal immune response,” Baum says.

Because of safety concerns, the researchers used a virus that causes only short-lived gene expression. Future research will be needed to develop methods that not only avoid an immune response but are also capable of longer-lived expression in salivary glands.

“These data will serve as stepping stones for other scientists to improve on this first attempt in the years ahead,” says Baum. “The future for applications of gene therapy in the salivary gland is bright.”

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.