Bacteria on Skin Boost Immune Cell Function

Bacteria on Skin Boost Immune Cell Function

The harmless bacteria that thrive on the skin can help immune cells fight disease-causing microbes, according to a new study in mice. The finding gives new insight into skin health.

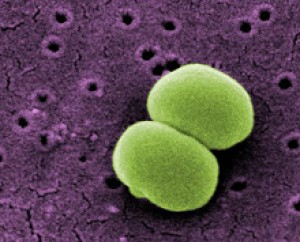

Staphylococcus epidermidis. Image by Janice Carr, courtesy of CDC/ Segrid McAllister.

Skin is a barrier that’s one of the first lines of defense against harmful microbes. Specialized immune cells within skin tissue also help to fight invading organisms. The skin’s surface is home to surprisingly diverse communities of bacteria, collectively known as the skin microbiota. Past research suggested that these bacteria might play a role in skin health and immune responses, but the details have been unclear.

In the new study, scientists took a closer look at how skin microbiota might influence immune cell function. The team was led by Dr. Yasmine Belkaid of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with colleagues at NIH’s National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and National Cancer Institute (NCI). Their report appeared in the early online edition of Science on July 26, 2012.

The scientists worked with special germ-free mice, born and raised with no naturally occurring microbes on the skin or in the gut. These mice, the researchers found, had weakened skin immune function compared to normal mice, which have vibrant bacterial communities on their skin. The skin tissue of normal mice contained a variety of immune cells known as T cells and diverse immune signaling molecules. Germ-free mice, in contrast, had significantly lower levels of certain signaling molecules and unusually high levels of a type of T cell that suppresses immune function.

In separate experiments, the researchers found that the presence or absence of microbes in the gut seemed to have no effect on the skin’s immune responses. This finding suggests that bacteria have unique roles at different sites in the body.

The investigators next colonized the germ-free mice with Staphylococcus epidermidis, one of the most common bacteria on human skin. Adding this one species of bacteria triggered an immune response in the skin and led to production of cell-signaling molecules that help to combat harmful microbes.

The researchers then infected germ-free mice with the skin parasiteLeishmania major. At the same time, some mice were also exposed to S. epidermidis, which colonized their skin. These colonized mice mounted an effective immune response to the parasite; the bacteria-free mice did not.

“We often have a sense that the bacteria that live on our skin are harmful,” says study co-author Dr. Julie Segre of NHGRI. “But in this study we show that these bacteria can play an important role in promoting health by preventing skin infections from becoming more prolonged, pronounced and more serious.”

“Certain inflammatory disorders of the skin have been linked to a change in the nature of the bacteria that we have on the skin, but the relationship between this change and disease was not clear,” Belkaid says. “Our findings provide a mechanistic link showing how these bacteria can manipulate immune responses and inflammation. What remains to be done—and what we are doing in collaboration with clinicians at NIH—is to see how relevant our findings in mice might be when applied to humans.”

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.