Ancient Roots of Social Networks

Ancient Roots of Social Networks

Modern social networks, from small networks of friends and family to entire countries, are based on cooperation. Individuals donate to the group and receive help back. A new study suggests that our early human ancestors may have had social networks strikingly similar to those of modern societies.

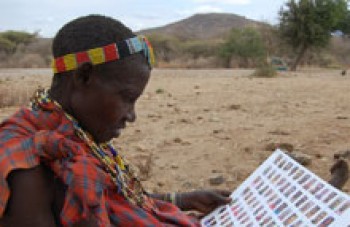

A Hadza woman picking out who’s in her social networks. Photo by Coren Apicella, Harvard Medical School.

Humans cooperate on many levels. We share food and resources with friends and family, we pay our taxes and we organize militaries to protect our citizens. Scientists have struggled to figure out how this level of cooperation evolved, since giving away your resources might seem to lower your chance of survival.

To gain insight, a team led by Dr. Nicholas Christakis of Harvard University set out to study social cooperation in hunter-gatherers, whose way of life is thought to be similar to our early ancestors. They studied the Hadza, a traditional hunter-gatherer society in remote Tanzania. Supported in part by NIH’s National Institute on Aging (NIA), the researchers investigated the social networks of 205 Hadza adults spread across 17 different hunter-gatherer camps. The results appeared in Natureon January 26, 2012.

Hadza camps reorganize frequently, and individuals often switch camps. The researchers asked study participants to name who they would like to have in their next camp. This formed a “campmate network.” The scientists then gave each person 3 sticks of honey and asked them to give the honey sticks away to 2 or 3 others. This formed a “gift network.”

By analyzing these 2 networks, the scientists found that Hadza social networks are similar in many ways to modern ones. For example, friendships decrease with increasing geographical distance, people tend to be close to their genetic relatives, and friends tend to name each other as friends. Like with modern societies, the Hadza participants had groups of friends, and friends tended to resemble each other in physical characteristics, like age, weight and height.

To study cooperation among the Hadza, the researchers created a public goods game. Each participant received 4 honey sticks. The participants could keep the honey sticks or donate them to the group. For each donated stick, the researchers added 3 more to the shared pot. At the end, the pot was divided equally among the group members.

The results of the public goods game were striking. While cooperation between camp groups varied significantly, there was little variation within groups. Cooperators tended to be friends with other cooperators, while non-cooperators tended to be friends with non-cooperators.

The researchers suggest 2 ways that groups might attain a particular level of cooperation: cooperators could choose to live with other cooperators, or social pressure could lead individuals to conform. Whichever is the case, this study suggests that the evolution of cooperation in our early human ancestors was partially a product of social networks.

“The astonishing thing is that ancient human social networks so very much resemble what we see today,” Christakis says. “From the time we were around campfires and had words floating through the air, to today when we have digital packets floating through the ether, we’ve made networks of basically the same kind.”

By Lesley Earl, Ph.D.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.