Neuroscientist Robert Doty Dies at 91

Neuroscientist Robert Doty Dies at 91

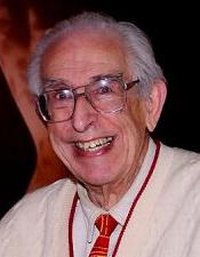

- Robert W. Doty, Ph.D.

Robert W. Doty, Ph.D., a leading brain researcher who helped create what is now the world’s largest organization of neuroscientists, the Society for Neuroscience, died Jan. 14 at home in Rush, N.Y. He was 91.

Plans for a memorial service to be held in the spring will be announced at a later date.

Dr. Doty had served the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry since 1961, a central figure to a team of people that has made the University an internationally recognized powerhouse in neuroscience. Dr. Doty helped to found two important research units at the University, the Center for Brain Research and the Center for Visual Science. During his 50 years at Rochester, Dr. Doty was a dedicated teacher and mentor, training more than 50 graduate students and post-doctoral researchers.

Dr. Doty grew up amid a family of modest means in Illinois, and after high school in Chicago, found himself on an assembly line building electric stoves and ranges. He attended night school and, with the encouragement of his father, began taking classes in accounting and business law, which he found “excruciatingly dull.” But at the library he started picking up books on all sorts of subjects, from philosophy to chemistry, and he had the good fortune of encountering tremendous night-school instructors through the University of Chicago.

When World War II began he became the foreman of a battery of automatic screw machines, making hardened cores for machine gun bullets. In his off hours he played the trumpet, which explains how, upon being drafted, he found himself a company bugle boy. He promptly applied to and was accepted into officer training school. Soon after, he became a transport commander in the Transportation Corps., making several voyages during the war to make sure the supplies and equipment needed by soldiers in combat reached their destinations safely. He traveled the seas from New York to Europe and Australia and Africa, transporting, for example, U.S. troops and refrigeration equipment to Africa and German prisoners of war back to New York. He escaped disaster thanks to a bout of food poisoning, which placed him on deck when the S.S. William S. Rosecrans steamship was struck by the enemy and sank off Naples, Italy in 1944.

After the war, he returned to Chicago to pursue his studies in science and was taught by leading scientists including Enrico Fermi, Willard Libby, Konrad Bloch and Roger Sperry. Dr. Doty ultimately earned bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees, all in physiology, from the University of Chicago.

He served on the faculty at the University of Utah and the University of Michigan before coming to the University of Rochester in 1961. For 35 years he served as a professor in the departments of Physiology and Psychology, as well as the Center for Brain Research and the Center for Visual Science. In 1996 he joined the faculty of the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy.

He was one of a handful of key people who helped create the Society for Neuroscience in 1969. The society now has more than 40,000 members – scientists and physicians devoted to advancing our understanding of the brain and nervous system as well as their disorders. Dr. Doty later served as president of the society, and even in recent years he made a habit to driving to its annual meetings, wherever they were – for instance San Diego, Atlanta, Chicago, and New Orleans.

In the research realm, Dr. Doty is best known for his work on how the left and right hemispheres of our brain work together through the corpus callosum, a bundle of nerves that connect the two halves. He studied how the hemispheres sometimes work independently and sometimes cooperatively in tasks like learning and memory.

He frequently conducted his experiments using vision as a tool to probe how the brain works, exploiting visual cues as a way to learn how memories are stored in the brain. Such research is crucial for physicians to understand how to better treat patients who have had a stroke or another type of traumatic brain injury.

In the 1970s Dr. Doty led a team that discovered brain cells known as luxotonic cells, very unusual cells that are sensitive to a wide range of light levels, from near darkness to extreme brightness. Scientists have taken a renewed interest in these cells in recent years, said David Williams, Ph.D., director of the Center for Visual Science. Scientists have discovered a previously unknown brain circuit that controls these cells and is involved in controlling the eye’s pupil size and the body’s circadian rhythm – new work made possible by Dr. Doty’s previous findings.

“Bob has been an incredible, supportive presence here for decades,” said Gary Paige, M.D., Ph.D., the chair of the Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, which held its annual banquet last year in honor of Dr. Doty. “He was famous for asking insightful questions at seminars that would oftentimes draw upon a deep – often old and established – literature.”

According to Paige, Dr. Doty was so devoted to his research that he kept his laboratory going long after he semi-retired in 1996, oftentimes using his own savings to buy equipment and supplies. He also donated funds to create an annual lectureship in his wife’s name and helped the faculty choose the scientists who were to be honored by being asked to deliver the lecture.

Dr. Doty was a fellow of the American Physiological Assn., the American Psychological Assn., the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Japan Society for Promotion of Science. He served as a visiting professor at University of Mexico and Osaka University in Japan.

A short autobiography by Dr. Doty, together with autobiographies of other founders of the Society for Neuroscience, was published a decade ago by the society. The autobiography is available at http://www.sfn.org/skins/main/pdf/history_of_neuroscience/hon_vol_3/c7.pdf

Dr. Doty is survived by four children: Robert W. Doty Jr. of Charlotte, N.C.; Mary Maher of Rochester; Cheryl A. Joyce of Phoenix, Az.; Richard M. Doty of Rush; and great grandchildren Annabelle and Elyssa Rheinwald of Henrietta. He was predeceased by his wife of 58 years, Elizabeth Jusewich Doty, who died in 1999.

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by University of Rochester Medical Center