Boosting Cell Defenses

Boosting Cell Defenses

Scientists designed a compound that successfully induces autophagy, a cell “housekeeping” process that may help fight cancer, infection, neurodegenerative disease and aging. The compound showed promise in laboratory cells and protected mice from deadly infection.

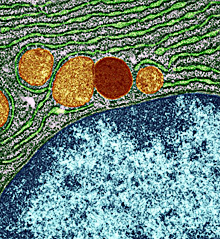

A lysosome, in red, within a cell. Image courtesy of University of Edinburgh, Wellcome Images. All rights reserved by Wellcome Images.

Waste within our cells is continually broken down and recycled through a process called autophagy. Damaged cell components and harmful debris are ultimately destroyed in an acidic compartment called the lysosome. This process plays a role in preventing disease, since harmful materials in the cell, including pathogens, can be digested and destroyed.

Abnormalities in autophagy have been tied to a broad range of diseases. These include cancer, neurological disorders and infection. Strategies to boost autophagy, then, may help prevent or treat a variety of conditions. Some drugs in clinical use are known to enhance autophagy but also have other effects. A drug that could specifically induce the process might have a wide range of uses.

A team led by Dr. Beth Levine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center set out to develop a specific autophagy-inducing agent. They began by exploring how an HIV protein called Nef blocks autophagy by interacting with the cellular protein beclin 1. Their study, which was partly funded by NIH, appeared on February 14, 2013, in Nature.

The researchers first mapped which portion of beclin 1 interacts with Nef and identified a sequence of 18 amino acids involved in Nef binding. They hypothesized that this stretch of amino acids might be able to induce autophagy. They thus designed a similar compound, called Tat–beclin 1, that can slip through cell membranes. The scientists found that Tat–beclin 1 was able to induce autophagy in various laboratory cell lines.

Further experiments showed that Tat–beclin 1 can boost the clearance of some protein clumps that have been tied to the neurodegenerative disorder Huntington’s disease. The compound also increased survival and reduced the levels of virus in cells infected by Sindbis virus, chikungunya virus and West Nile virus. In addition, it had antibacterial effects against the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, which causes foodborne illness. The compound inhibited HIV-1 replication in cells as well.

Tat–beclin 1 boosted autophagy in live mice, too, the scientists found. They next tested the compound in mice infected with the chikungunya and West Nile viruses. Tat–beclin 1 significantly reduced mortality.

The scientists explored the role of Tat–beclin 1 in the cell and found that it binds to a protein called GAPR-1. Further investigation revealed that GAPR-1 inhibits autophagy. By binding to GAPR-1, Tat–beclin 1 reverses that inhibition to induce autophagy.

These findings now provide further opportunities to explore the autophagy pathway and its role in cancer, infection, neurodegenerative disease and aging. “Because autophagy plays such a crucial role in regulating disease, autophagy-inducing agents such as the Tat–beclin 1 peptide may have potential for pharmaceutical development and the subsequent prevention and treatment of a broad range of human diseases,” Levine says.

By Harrison Wein, Ph.D.

###

* The above story is reprinted from materials provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH)

** The National Institutes of Health (NIH) , a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the nation’s medical research agency—making important discoveries that improve health and save lives. The National Institutes of Health is made up of 27 different components called Institutes and Centers. Each has its own specific research agenda. All but three of these components receive their funding directly from Congress, and administrate their own budgets.