University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Information.

Sections for University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

- About University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

- University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Information.

University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Information.

Leading the Way

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It is the only campus in the 10-campus UC system dedicated exclusively to the health sciences.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Mission & Vision.

The mission of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is advancing health worldwide™. To fulfill this mission, UCSF outlined these six goals in its first-ever strategic plan:

- Develop the world’s future leaders in health care delivery, research and education. UCSF is currently at the forefront of health sciences education, and is well positioned to meet the growing demand for health professionals and scientists. The development of the next generation of leaders in health care delivery, research and education is vitally important to the economic and social well-being of California and the world.

- Be a world leader in scientific discovery and its translation into exemplary health. The pace of major scientific and technological discovery is remarkably rapid. But meaningful translation of these developments into treatments and disease prevention is lagging. UCSF is uniquely poised to alter this trend by creating new research models that accelerate translation. UCSF boasts an exceptional cadre of distinguished investigators, a diverse portfolio of leading-edge research programs spread across four preeminent health professional schools, a pioneering health care enterprise and an unparalleled spirit of cooperation.

- Provide high-quality, patient-centered care leading to optimal outcomes and patient satisfaction. This goal commits the clinical enterprise to the core principle that care at UCSF is patient-centered. It also recognizes that UCSF’s students receive their best training in an institution that has systems and staffing that are designed to optimize outcomes and eradicate medical errors. This commitment was reiterated in the UCSF Clinical Enterprise Strategic Plan adopted in the fall of 2008.

- Educate, train and employ a diverse faculty, staff and student body. Offering a wide range of educational and career opportunities for students, faculty and staff, UCSF seeks candidates whose life experience, work experience or community service has prepared them to contribute to UCSF’s commitment to diversity and excellence. Diversity is a defining feature of California’s past, present and future, and refers to the variety of personal experiences, values and worldviews that arise from differences in culture and circumstance. Such differences include race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, language, abilities/disabilities, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status and geographic region, among others.

- Provide a supportive and effective work environment to attract and retain the best people and position UCSF for the future. Recruiting and retaining excellent faculty and ensuring that they have an environment that supports their academic and personal needs are essential to maintaining the international stature and reputation, and thus the future, of UCSF. To achieve all of UCSF’s long-term goals, which are ambitious and far-reaching, leadership and participation by faculty of the highest caliber are critical. Likewise, recruiting and retaining excellent staff are equally essential to supporting the academic community to continue the outstanding research, teaching, community service and health care.

- Serve the local, regional and global communities and eliminate health disparities. Community and public service is integral to the UCSF vision of advancing health worldwide™. Whether focusing on breakthroughs in basic science research, devising innovations in patient care, or training the next generation of leaders in health sciences and health care, UCSF faculty, staff, students and trainees share a common purpose of wanting to make a difference to improve the health of people in the local, regional and global communities. As a public university, UCSF has a particular responsibility to ensure that it contributes to the public good and is an exemplar of civic responsibility. Striving to eliminate health disparities is one important part of this social responsibility.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.

UCSF’s Parnassus campus is located in a neighborhood

above Golden Gate Park known as Parnassus Heights.

Health Sciences University

UCSF is the only campus in the 10-campus University of California system devoted exclusively to the health sciences.Chancellor

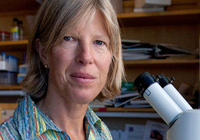

Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, MPH, is UCSF chancellor. The ninth chancellor and first woman to lead UCSF, she assumed the top post on Aug. 3, 2009. Desmond-Hellmann is also the Arthur and Toni Rembe Rock Distinguished Professor.

Mission

UCSF is committed to a mission that is active and ongoing: advancing health worldwide™, adopted in 2007 as part of the UCSF Strategic Plan.

Vision

Chancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann announced a vision for UCSF during her State of the University Address on Oct. 4, 2011. UCSF’s vision is to be the world’s preeminent health sciences innovator.

Brief History

UCSF dates its founding to 1864, when Toland Medical College was established in San Francisco. Toland Medical College became affiliated in 1873 with the University of California, which at the time consisted of a single campus in Berkeley. Toland and the California College of Pharmacy were affiliated colleges that provided a health sciences base in San Francisco. This base continued to expand with the addition of dentistry and nursing colleges and a hospital. In 1949, the institution was renamed UC Medical Center in San Francisco, and in 1964, it gained administrative autonomy, becoming the ninth campus in the UC system. In 1970, the UC Board of Regents renamed the campus the University of California, San Francisco in recognition of its diversity of disciplines.

Workforce

UCSF is the second-largest employer in San Francisco, after the city and county of San Francisco, and the fifth-largest employer in the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area. UCSF’s paid workforce numbers about 22,500, which includes both University and UCSF Medical Center employees. The paid workforce comprises about 2,400 faculty and 20,100 staff.

Students, Residents and Postdoctoral scholars

UCSF has approximately:

- 2,940 students enrolled in degree programs

- 1,620 residents (physicians, dentists and pharmacists in training)

- 1,030 postdoctoral scholars

- Students, residents and postdoctoral scholars at UCSF represent 94 countries.

Trio of Top Awards

In 2009-2010, UCSF became the only institution to claim faculty who earned the Nobel Prize, Albert Lasker Award and Shaw Prize within a single academic year. The recipients are Elizabeth Blackburn, PhD, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award; and David Julius, PhD, Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine.

Nobel Laureates

UCSF recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and the year of their awards:

- J. Michael Bishop, MD, and Harold Varmus, MD, for discovery of proto-oncogenes, showing that normal cellular genes can be converted to cancer genes (1989).

- Stanley Prusiner, MD, for discovery of prions, an entirely new biological principle of infection and disease. Prions cause degenerative brain disorders, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in people and mad cow disease (1997).

- Elizabeth Blackburn, PhD, for discovery of an enzyme that plays a key role in normal cell function as well as in cell aging and most cancers. The enzyme, called telomerase, produces tiny units of DNA that seal off the ends of chromosomes, which contain the body’s genes. She shared the award with Carol W. Greider of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Jack W. Szostak of Harvard Medical School (2009).

Faculty Excellence

The number of faculty who have received the following major awards:

The number of faculty who have received the following major awards:

- Nobel Prize winners: 4

- Albert Lasker Award: 8

- Shaw Prize in Life Sciences and Medicine: 4

- National Medal of Science: 4

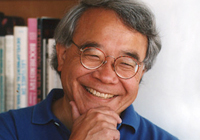

Stem cell researcher Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD, an investigator at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease and a professor of anatomy at UCSF.

The number of UCSF faculty who are current members or fellows of the following prestigious scientific honorary organizations:

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences: 61 (updated October 2011)

- Howard Hughes Medical Institute: 18

- Institute of Medicine: 80 (updated October 2011)

- National Academy of Sciences: 42

- American Association for the Advancement of Science: 66

Scholarly Productivity

UCSF faculty are ranked third for “scholarly productivity” among all universities and research institutes worldwide, according to 2007 data published by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Economic Impact

According to a 2010 economic impact report, UCSF generates:

- In San Francisco: 32,110 jobs (including those at UCSF) and produces an estimated economic impact of $4.7 billion when including operations, construction, salaries, and local purchases by employees, students and visitors.

- In the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area: 39,134 jobs (including those at UCSF) and produces an estimated economic impact of $6.2 billion when including operations, construction, salaries, and local purchases by employees, students and visitors.

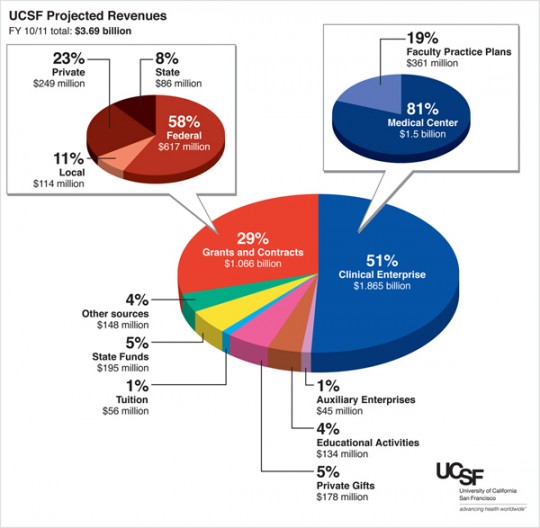

Budget

A $3.6 billion enterprise, UCSF receives more than half – $ 1.9 billion – from UCSF Medical Center and almost $1 billion from grants and contracts, which includes a substantial amount from the National Institutes of Health, to support its core activities. UCSF receives $250 million or 6.9 percent of its revenues from state appropriations for education. Operating expenses for fiscal year 2010 were almost $3.3 billion.

Private Support

UCSF received close to $269 million in total private support in fiscal year 2010, marking the 10th consecutive year in which total private support of UCSF exceeded $200 million.

Patents

Two UCSF-patented inventions – hepatitis B vaccine and artificial growth hormone – accounted for 45 percent of the top five income-earning patents of the entire University of California system in 2009. The hepatitis B vaccine is the system’s top-earning patent. Other highlights:

- From 1977 to 2009, 1,757 UCSF patents were issued.

- From 2000 to 2009, 602 UCSF patents were issued (more than any other UC campus).

- From 2008 to 2009, average income to UCSF from patent royalties, fees and litigation settlements was $64 million.

- The 2006 global survey conducted by the Milken Institute ranked UCSF No. 2 in the world for issued US life science patents.

Start-up Companies

Since the early 1970s, an estimated 90 life science companies have been spawned from UCSF research, including more than 40 start-ups at Mission Bay.

Research Funding

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest source of funding for medical research in the world, funding thousands of scientists in universities and research institutions in every state across America and around the globe. NIH support to UCSF reflects research and training grants, fellowships, and other awards, calculated according to the federal fiscal year 2009. Among the NIH highlights:

- UCSF received about $463 million in total NIH research support, making it the top recipient among public institutions and the second-highest among all institutions nationwide.

- UCSF overall and each of its schools have ranked among the top four in total NIH funding for more than a decade.

- The UCSF School of Pharmacy was the highest-ranking school in the country in NIH support, with $19 million.

- The UCSF School of Medicine ranked second nationwide in NIH support, with $409 million. The medical school also received another $8.7 million in overall medical grants in a separate NIH ranking, for a total of $417.7 million.

- The UCSF School of Dentistry received about $15.5 million and the UCSF School of Nursing received $8.8 million in NIH support – making both schools second in the nation in their respective fields.

- The UCSF schools of dentistry, nursing and pharmacy have ranked first or second in NIH support for several decades.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) is legislation, signed into law by President Barack Obama on Feb. 17, 2009, that authorizes $10.4 billion in economic stimulus funds to the NIH to be spent entirely before October 2010.

- As of Nov. 3, 2010, UCSF has been named to receive 360 grants totaling $166.5 million through ARRA, making UCSF one of the top institutional recipients of this stimulus-based scientific funding. The majority of these awards are through grants from the NIH. As of Sept. 14, 2010, UCSF had received $31.2 million of those funds, making it possible to retain or create 287.77 jobs in research or associated areas.The federal government is the largest source of academic research and development (R & D) funding.

-

UCSF’s investment in R&D expenditures was $885 million in fiscal year 2008, making it the largest performing public institution and second among all institutions nationwide in R&D in the fields of science and engineering, according to data reported by the National Science Foundation.

Education

UCSF is renowned for its excellence in educating and training students in the health professions. The UCSF schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy and the Graduate Division all rank among the nation’s most prestigious advanced study programs in the health sciences.

Graduate degrees offered at UCSF are dentistry (DDS, PhD, MS), medicine (MD, MD-PhD, DPT), nursing (PhD, MS), pharmacy (PharmD), Graduate Division (master’s and doctoral). Key facts about UCSF are:

- The UCSF School of Dentistry is recognized nationwide for its innovative approaches to dental education, including combined DDS-PhD and DDS-MBA programs and a special one-year training course geared to helping disadvantaged students gain admission to US dental schools.

- The UCSF School of Medicine is the only school in the country to rank among the top five in both research and primary care in the new (2010-2011) survey on America’s best graduate schools by US News & World Report. UCSF is tied for No. 4 in research and tied for No. 5 in primary care.

- The UCSF School of Nursing ranked No. 2 in the nation in the most recent (2007) US News & World Reportsurvey on best nursing schools.

- The UCSF School of Pharmacy ranked No. 1 in the nation in the most recent (2008) US News & World Reportsurvey of best schools of pharmacy.

- The Graduate Division’s PhD programs rank at the top nationally, including several in the top 10, according to the prestigious National Research Council’s 2010 survey. The seven programs in the top 10 are: nursing, bioengineering, biochemistry and molecular biology, neuroscience, biophysics, biomedical sciences, and cell biology. Another five programs are rated among the nation’s best: medical anthropology, chemistry and chemical biology, sociology, genetics, and oral and craniofacial sciences.

For students, getting into UCSF is highly competitive. In fall 2010, the number of admissions versus applications was:

- School of Dentistry (DDS), 112 out of 1,996

- School of Medicine (MD), 151 out of 6,413

- School of Nursing (master’s), 203 out of 836

- School of Pharmacy (PharmD), 123 out of 1,604

- Graduate Division (PhD), 125 out of 1,851

The UCSF Fresno program supports UCSF’s educational mission. Students from UCSF’s four schools (dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy) and residents from three schools (dentists, physicians and pharmacists in training) have the opportunity to take a rotation in the program. Based in Fresno, the program is affiliated with regional hospitals and medical centers, and plays a vital role in supporting local health care needs.

Patient Care

Key facts about the UCSF clinical enterprise:

- UCSF Medical Center, with hospitals located at Parnassus Heights and Mount Zion, has 559 licensed beds.

- UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital has 163 licensed beds.

- UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital are under the same license. Together, they see about 30,000 inpatients and generate about 763,000 outpatient visits per year.

- Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital and Clinics, which has 67 licensed beds, is under a separate license and sees 720 inpatients and 33,500 outpatient visits per year.

- The UCSF Dental Center operates 14 clinics (based at three sites in San Francisco) and sees 121,000 patients per year.

Other highlights:

Other highlights:

- UCSF Medical Center is ranked seventh nationwide in the 2010-2011 best hospitals report by US News & World Report, making it the highest-ranked medical center in Northern California. It is the 11th consecutive year in which UCSF Medical Center ranks in the prestigious top 10.

- UCSF Medical Center’s nationally preeminent programs include children’s health, the brain and nervous system, organ transplantation, women’s health, and cancer.

- UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital is ranked among the best in the nation in eight pediatric specialties in the 2010-2011 US News & World Report survey on best children’s hospitals, making it one of the top four pediatric facilities in California.

- UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital has more than 150 experts in 40 medical specialties and admits about 5,000 patients a year, including 1,800 babies who are born in the hospital each year.

- A new UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay is under construction and scheduled to open in 2015. It will be a 289-bed, integrated hospital complex serving children, women and cancer patients.

- Langley Porter Psychiatric Hospital and Clinics is the clinical arm of the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute (LPPI), located on the UCSF campus at Parnassus Heights. LPPI is recognized as one of the nation’s foremost resources for comprehensive and compassionate patient care, research and education in the field of mental health.

- In addition to its programs at Parnassus Heights, Langley Porter treatment programs are active at San Francisco General Hospital, at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and in Fresno through the UCSF Fresno Program.

- The UCSF Dental Center is operated by the UCSF School of Dentistry as part of its mission to educate students and to provide health services to the public. The clinics provide comprehensive dental care services, including complex oral and maxillofacial surgery and care for special-needs patients.

San Francisco Presence

UCSF has three major, multibuilding campus sites in San Francisco: Parnassus Heights, Mission Bay and Mount Zion. In addition, major programs and departments are located at 19 sites owned or leased by UCSF throughout the city and at two UCSF affiliates, San Francisco General Hospital and San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Affiliates

San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) has been a partner with UCSF in public health since 1873. Faculty from all four UCSF schools – dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy – work at SFGH, where they provide patient care treatment and services, conduct research and teach. All physicians at SFGH hold UCSF faculty appointments.

Today, the SFGH workforce includes almost 2,000 UCSF employees (physicians, specialty nurses, health care professionals and others) who work side by side with 3,500 city employees. SFGH serves as a major teaching hospital for UCSF residents and fellows.

San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC) is owned by the US Department of Veterans Affairs and is affiliated with all four UCSF schools: dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy. More than 240 full- and part-time UCSF physicians are on staff at SFVAMC and provide patient care. SFVAMC serves as a major teaching hospital for UCSF residents. It funds 171 positions for UCSF residents who train at SFVAMC, and provides clinical training for one-third of UCSF medical students.

The J. David Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit biomedical research institution comprising three institutes devoted to the study of cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Gladstone is located adjacent to the UCSF Mission Bay campus. Through the institutes’ affiliation with UCSF, Gladstone investigators hold UCSF faculty appointments and participate in many University activities, including the teaching and training of graduate students.

Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center is an independent, nonprofit organization focusing on the study of the biological basis of alcohol abuse and substance abuse. The Gallo Center is located in Emeryville, California. All Gallo Center faculty hold appointments in departments and interdisciplinary graduate programs at UCSF, and most receive grant support from the National Institutes of Health.

Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) is a nonprofit medical research organization, and UCSF serves as one of its host institutions. Based in Chevy Chase, Maryland, HHMI appoints leading scientists as HHMI investigators, providing funds to support their research at their home institutions. Selection as an HHMI investigator is a prestigious appointment, and several UCSF scientists are part of this group.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). UCSF’s 2014-2015 Plan.

UCSF Chancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann and her leadership team developed a three-year action plan with a vision for UCSF to become the world’s preeminent health sciences innovator and five goals.

2014-2015 Plan

– VISION:

To be the world’s pre-eminent health sciences innovator.

– MISSION:

UCSF advances health worldwide through innovative health sciences education, discovery and patient care.

GOAL 1: Provide unparalleled care to our patients

STRATEGIES

STRATEGIES

- Hire and retain top health care providers

- Accelerate the translation of groundbreaking science into therapies for our patients

- Provide a world-class patient experience

GOAL 2: Improve health through innovative science.

- Promote collaboration and cross-disciplinary efforts within the UCSF research community

- Invest in infrastructure that enables UCSF to excel in basic, clinical and population research

- Lead and influence biomedical research policy at the national level

STRATEGIES

- Increase professional and graduate student financial support

- Develop infrastructure to support new experiential, team-based, interdisciplinary teaching models

- Create a learning environment in which our trainees thrive

STRATEGIES

STRATEGIES

- Establish and communicate clear goals and direction — at all levels

- Enhance development opportunities for faculty and staff

- Compensate faculty and staff based on performance and at market levels

- Create an environment in which faculty and staff can thrive

GOAL 5: Create a financially sustainable enterprise-wide business model

STRATEGIES

- Collaborate with our local community on educational and economic opportunities and health enhancement

- Design and implement transparent and effective budgeting and planning processes

- Maximize existing revenue streams, develop new ones and continue Operational Excellence efforts to manage costs

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). History.

One of the world’s leading health sciences universities, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), dates its founding to 1864, when South Carolina surgeon Hugh Toland founded a private medical school in San Francisco.

Toland had come west in 1849 to seek his fortune in the California Gold Rush, but after a few discouraging months as a miner, he set up a surgical practice in booming San Francisco. As his wealth and influence grew, he purchased land in North Beach and opened Toland Medical College.

The Affiliated Colleges, initially located at various sites in San Francisco, were united on a site overlooking Golden Gate Park — known today as Parnassus Heights.

The Affiliated Colleges, initially located at various sites in San Francisco, were united on a site overlooking Golden Gate Park — known today as Parnassus Heights.

The college prospered, and Toland sought to affiliate with the University of California, which had opened its campus in Berkeley in 1868. UC President Daniel Coit Gilman, who strongly supported science education, set a precedent for the young university by affiliating in 1873 with both Toland Medical College and the California College of Pharmacy. Eight years later, the UC Regents added a dental college.

The three Affiliated Colleges — also called UC departments — were located at various sites in San Francisco, and after several years there was strong interest in bringing them together. San Francisco Mayor Adolph Sutro donated 13 acres on a site overlooking Golden Gate Park — known today as Parnassus Heights — and the new Affiliated Colleges buildings opened in fall 1898.

Establishing an Academic Medical Center.

When the great San Francisco earthquake destroyed much of San Francisco and the city’s medical facilities in April 1906, more than 40,000 people took shelter and sought treatment in a tent city in Golden Gate Park, where makeshift outdoor hospitals were set up. The Affiliated Colleges, located on the hill above the encampment in what was then the far western section of the city, suddenly were situated close to a significant population. Faculty sprung into action treating those injured from the earthquake and subsequent fire.

More than 40,000 people took shelter and sought treatment in a tent city in

Golden Gate Park after the great 1906 earthquake in San Francisco.

Previous interest in establishing a UC teaching hospital on the Parnassus site took on momentum as a civic responsibility to provide care in an area where it was needed. This type of commitment to community service had been put in motion through an 1873 agreement struck by leaders of the Affiliated Colleges with the city to provide patient care at its public health hospital (later named San Francisco General Hospital).

One of the Affiliated Colleges buildings at Parnassus Heights was renovated as a facility

for inpatients, outpatients and dental services, and opened in April 1907 with 75 beds.

With this new facility came the need to recruit nurses and the opportunity to train nursing students. In 1907, the UC Training School for Nurses was established, adding a fourth professional school to the Affiliated Colleges. To make room for expanded clinical services and instruction on Parnassus, the medical college basic science departments — pathology, anatomy and physiology — moved to the Berkeley campus.

In 1911, the last member of the American Indian Yahi tribe began living on the Parnassus campus. He was starving when he walked out of the wilderness in Oroville, Calif., capturing the attention of UC anthropologists who brought him to San Francisco. They named him Ishi, for “man” in the Yahi language. Over the next few years, UC physicians and anthropologists learned about Yahi culture from Ishi, and on weekends, hundreds flocked to the anthropology museum to watch him demonstrate arrow-making and other life skills. He continued to live on Parnassus until 1916, when he died of tuberculosis.

Over the next 50 years, leaders of the Affiliated Colleges and UC moved forward with an eye to establishing an institution with a national reputation. They improved the curriculum, upgraded admission requirements, expanded research and clinical programs, and built new facilities.

One key achievement came in 1914, when the Hooper Foundation for Medical Research selected Parnassus as the site for its work. Second in size only to New York’s Rockefeller Institute, Hooper was the first medical research foundation in the United States to be incorporated into a university.

The George Williams Hooper Foundation added prestige to the Parnassus site amidst ongoing debate by UC leaders and faculty about the best location for the medical college: San Francisco or Berkeley. Fueling the discussion was a rumor that a major Rockefeller endowment would support a school of public hygiene on the Berkeley campus, but only if the medical college was located there. In a series of votes over the next three decades, the UC Regents supported consolidation of all clinical instruction and basic science departments in San Francisco, but the debate continued.

In 1949, the Regents designated the Parnassus campus as UC Medical Center in San Francisco. It still took several years for all the basic science departments to move back from the East Bay, due in part to the need to secure construction funds for new facilities to house them. When the Medical Sciences Building was completed in 1958, the basic science departments had a new home on the same campus as the clinical departments, uniting the medical college for the first time in 50 years.

Meanwhile, several new research institutes had been established and clinical services expanded.

In 1942, the Langley Porter Clinic, which would later become the neuropsychiatric institute,

opened its new building at Parnassus Heights.

New clinical facilities had opened about every 10 years, lining and defining Parnassus Avenue: the 225-bed UC Hospital (1917), Clinics Building (1934), Langley Porter Clinic (1942) and Herbert C. Moffitt Hospital (1955).

A highlight of the growth was an art project funded by the Works Progress Administration, setting the stage for a tradition of public art that has continued at UCSF. Artist Bernard Zakheim, a student of Diego Rivera, was commissioned in 1938 to paint a series of murals depicting the history of medicine in the lecture auditorium of UC Hospital, now UC Hall.

By 1958, Parnassus was home to the Biomechanics Laboratory, Cancer Research Institute, Proctor Foundation for Research in Ophthalmology, Metabolic Research Unit and Cardiovascular Research Institute. The addition of Guy S. Millberry Union, also in 1958, provided dorms and support services for students.

Gaining Autonomy.

By the 1960s, the campus had shed its identity as “Cal’s Medical Center” and gained more autonomy as the entire UC system moved to decentralize. Each of the four schools by this time had been renamed “school of” in alignment with other UC campuses, and in 1961 the Graduate Division was established.

American photographer and San Francisco native Ansel Adams (1902-1984) visited UCSF during his long career, capturing this moment at UCSF Medical Center during the 1960s.

American photographer and San Francisco native Ansel Adams (1902-1984) visited UCSF during his long career, capturing this moment at UCSF Medical Center during the 1960s.

In 1964, the institution, operating under the name University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, was given full administrative independence, becoming the ninth campus in the UC system and the only one devoted exclusively to the health sciences. Provost John B. de C.M. Saunders, MD, was named the first chancellor.

Although popular with clinicians, Saunders was not as well received by researchers. He believed that training students and healing patients were paramount duties of the campus, with research ranking third. Faculty concerns led the UC Regents to ask him to step down, and in 1966 he resigned the post and took on a faculty appointment. That year, the Health Sciences East and Health Sciences West towers opened, which gave another boost to the research enterprise.

The same year, Willard C. Fleming, DDS, became the second chancellor and one of a few dentists to head a health sciences center. He was specifically chosen from outside the medical school to avoid further conflict between clinicians and researchers, and he provided the needed stabilization. The campus was on the road to becoming a full-fledged research university.

The medical school also had expanded its programs by entering into an affiliation agreement in 1968 to manage patient care, teaching and research at the San Francisco Veterans Administration (now Veterans Affairs) Medical Center (VAMC). Within 10 years, the San Francisco VAMC became a model of research and patient care for VA medical centers nationwide, a recognition that remains today.

Philip R. Lee, MD, became UCSF’s third chancellor in 1969, coming to UCSF from an assistant secretary post in the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare. He led the campus during a time of political and social turmoil, and he was recognized especially for efforts to increase minority recruitment and enrollment. Lee stepped down from the chancellor’s post in 1972 and established the UCSF Health Policy Program, the first program of its kind in the country and today the center bears his name.

Catapulting in Stature.

During Lee’s tenure, the UC Regents in 1970 fittingly renamed the institution the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) in recognition of its diversity of disciplines. The “medical center” name continued as a reference to patient care services.

By the time it got its new name, UCSF already had catapulted to the top ranks of US institutions in the health sciences through its reforms in graduate education and interschool collaboration — particularly integrating basic science instruction with clinical instruction — and its faculty leaders in research discoveries and clinical treatments.

Francis Sooy became UCSF’s fourth chancellor in 1972.

Francis A. Sooy, MD, became the fourth chancellor in 1972, holding the post for the next 10 years. He recruited outstanding physicians and researchers for some of the top campus positions, including three deans, and with other campus leaders worked to strengthen UCSF’s established excellence by expanding programs.

But more space was needed.

The nursing school opened its own building in 1972, and the medical center opened the Ambulatory Care Center in 1973 to meet the increased demand for outpatient care. Plans for more expansion were not popular with the surrounding neighborhood, which led to extensive negotiations. In 1976, UCSF and community residents, with UC Regents’ approval, agreed on campus boundaries and designation of Mount Sutro as an open space reserve, a wilderness area that remains today.

With campus space limitations in place, Parnassus scientists worked in cramped quarters that prevented some from pursuing additional research and gaining National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding. Ironically, the circumstances also fostered new collaborations.

Research was moving in new directions in the mid-1970s as a result of the discovery of recombinant DNA technology by UCSF and Stanford scientists and the promises offered by the new field of biotechnology.

The UCSF campus at Parnassus Heights as seen in 1988.

UCSF patient care specialists were pioneering a range of innovative diagnostic procedures and treatments, including genetic tests for inherited blood disease, therapies for newborn lung disease, methods to correct heart rhythm disorders without surgery, and surgery in the developing fetus to correct life-threatening problems. All of these breakthroughs have significantly improved and saved lives.

Around the same time, UCSF expanded its educational outreach by establishing the UCSF Fresno Medical Education Program in 1975. The program has since grown to include all four schools, providing an opportunity for students and residents to train in the Central Valley and support local health care needs.

Experiencing Explosive Changes.

In 1982, Julius R. Krevans, MD, became UCSF’s fifth chancellor. A distinguished physician and educator, Krevans’ professional career was devoted to the academic community. He played an important role nationally in developing public policy in medical education and the health sciences, and in advancing biomedical research.

During the 1980s and 1990s, UCSF already was one of the largest recipients of funding from the NIH and was experiencing explosive changes in science, further pushing the need for more research space. Some campus buildings were modernized and others were demolished to make way for construction of new facilities. But to meet the space demand, UCSF leaders also looked beyond Parnassus Heights.

The Parnassus campus had opened the Marilyn Reed Lucia Child Care Center in 1978, and it continued to take on a new look with the opening of the Dental Clinics Building (1980); the new Joseph M. Long Hospital (1983), which was integrated with the existing Moffitt Hospital; Beckman Vision Center and Koret Vision Research Laboratory (1988); and Kalmanovitz Library (1990).

The UCSF School of Dentistry opened its Dental Clinics

building on the Parnassus campus in 1980.

UCSF also began moving into other parts of the city.

In the Laurel Heights neighborhood, UCSF bought the Fireman’s Fund building in 1985, renaming it UCSF Laurel Heights. It was planned as a site for pharmacy school laboratory research and instruction, but neighborhood concerns about lab projects forced UCSF to consider other uses for the building. Over the next few years, the building developed as the home for academic desktop research, social and behavioral science departments, and administrative offices.

In the Western Addition, UCSF acquired Mount Zion Hospital in 1990, which became UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion. It served as a second major clinical site and, in 1999, also became home to the first comprehensive cancer center in Northern California to have the National Cancer Institute designation. The center later was named the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In 1993, Joseph M. Martin, MD, became UCSF’s sixth chancellor. He and Haile T. Debas, MD, dean of the UCSF School of Medicine, were instrumental in leading the discussion and merger with Stanford that created UCSF Stanford Health Care and in gaining critical community support for developing Mission Bay as the site for a second major campus for research and teaching.

The UCSF-Stanford merger was prompted by practical discussions between institutional leaders on how their medical schools and medical centers could share more and compete less in an era of declining federal funding and Medicare payments and of managed care. The talks led to a bold move to establish a merged health care system as a private, nonprofit corporation, keeping the medical schools and medical faculties independent. In 1997, UCSF Stanford Health Care began operating, but the goal of creating a single clinical entity with integrated service lines and increased clinical activity was not accomplished. The merger officially dissolved in spring 2000.

Developing Mission Bay.

After a landmark deal struck by Bruce Spaulding, vice chancellor of University Advancement and Planning at UCSF, Nelson Rising, chief executive officer of Catellus Development Corp. and San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, UCSF broke ground for the Mission Bay campus in 1999.

UCSF leaders spent several years evaluating different sites in all parts of the Bay Area and meeting with civic, business and community members before deciding to keep the second campus in San Francisco. Once occupied by old warehouses and rail yards, the initial Mission Bay campus land parcel included 42.4 acres: 29.2 acres donated by Catellus and 13.2 acres donated by the city of San Francisco. Later, an adjacent 14.5-acre parcel was added as the site for a new UCSF Medical Center, bringing the total campus to about 57 acres.

In 1997, Debas became UCSF’s seventh chancellor, agreeing to take the post for one year during the important period when the UCSF-Stanford merger and Mission Bay planning were advancing. He was an internationally renowned surgeon, scientist and teacher, and during his tenure, UCSF became one of the country’s leading centers for transplant surgery, training young surgeons, and basic and clinical research in surgery.

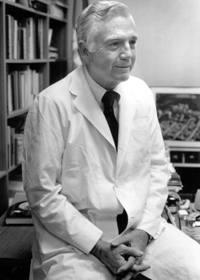

J. Michael Bishop, MD, a noted scientist who was a recipient of both the Lasker Award and Nobel Prize (with Harold Varmus, MD), became the eighth chancellor in 1998. He is recognized for steering UCSF through one of its most expansive periods of growth and achievement, including developing the Mission Bay campus from the ground up, establishing innovative research programs, and garnering record philanthropic support.

UCSF broke ground for a second major campus for teaching and research at

Mission Bay in 1999. The first building opened in 2003.

The Mission Bay campus became home to a vibrant community of scientists, scholars, students and staff. The first building, Genentech Hall, was occupied in 2003, followed by Arthur and Toni Rembe Rock Hall (2004), Byers Hall, William J. Rutter Center and Mission Bay Housing (2005), University Child Care Center (2006), and Helen Diller Family Cancer Research Building (2009), plus new quarters adjacent to the campus for the Orthopaedic Institute (2009).

As chancellor, Bishop, working with Eugene Washington, MD, executive vice chancellor and provost, unveiled the first comprehensive, campuswide strategic plan and laid the foundation for ongoing programs to enrich diversity and create a supportive work environment. UCSF also adopted a new mission: advancing health worldwide™.

Pursuing Continued Excellence.

In August 2009, Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, MPH, who previously served as president of product development at Genentech, took the helm as the ninth chancellor and first woman to lead the campus where she received her medical training. Faced immediately with a weak economic environment marked by ongoing cuts in state funding, she named five priorities — patients and health, discovery, education, people, and business — to guide UCSF in its pursuit of continued excellence.

Supporting her priorities was the opening of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCSF’s Parnassus campus. The center brings stem cell scientists together under one roof, enhancing their collaborative efforts in developing novel treatments for such diseases as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, HIV/AIDS and cancer.

In addition, the children’s hospital was renamed UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in honor of the donors of a major gift toward a new facility at Mission Bay designed specifically for children and their families, and the Parnassus campus celebrated the opening of the Kirkham Child Care Center, the University’s fourth child care facility.

At Mission Bay, 2010 marked the opening of the Smith Cardiovascular Research Building, the new headquarters of the UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute. The building features an outpatient clinic providing state-of-the-art services and open, shared labs where researchers focus on understanding cardiovascular disease and developing new treatments.

The Mission Bay campus also hosted groundbreakings for a neurosciences building and a new medical center, setting the stage for additional health care advances in the future.

The Neurosciences Laboratory and Clinical Research Building, scheduled for completion in 2012, will house clinical and basic research programs seeking cures for intractable neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and cerebral palsy.

The new UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay will be a 289-bed integrated hospital complex and world-class facility serving children, women and cancer patients, with the first phase set to open in 2014.

Looking ahead, 2014 also will mark the sesquicentennial of UCSF’s founding and 150 years of achievements.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Achievements.

It is no small task to recount the major basic science and clinical research accomplishments that span the history of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Here is a fairly comprehensive list that gives credit to the researchers who took the lead to make these discoveries dating back to 1914.

UCSF’s Nobel laureates are, from left, Elizabeth Blackburn (2009), Stanley Prusiner (1997), and co-recipients J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus (1989).

UCSF’s Nobel laureates are, from left, Elizabeth Blackburn (2009), Stanley Prusiner (1997), and co-recipients J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus (1989).

2011

- Proved definitively that fetal surgery can help repair the birth defect spina bifida. Babies who undergo the prenatal procedure experience fewer neurologic complications than babies who have corrective surgery after birth, according to findings from a major multicenter randomized trial led by UCSF researchers. The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is the first to systematically evaluate the best treatment for myelomeningocele, the most serious form of spina bifida, in which the bones of the spine do not fully form. The surgical procedures evaluated in the trial were developed at the UCSF Fetal Treatment Center under the direction of Michael Harrison, MD, a UCSF professor emeritus considered the “Father of Fetal Surgery.”

2010

- First use in humans of a new technology that monitors changes in hyperpolarized pyruvate, a naturally occurring sugar that cells produce during metabolism, in order to rapidly assess the aggressiveness of a tumor by imaging its metabolism. The technique has the potential for dramatically changing treatment for many types of tumors by providing immediate feedback to clinicians on whether a therapy is working. (Sarah Nelson, PhD; Daniel Vigneron, PhD; John Kurhanewicz, PhD; Marcus Ferrone, PharmD; and Andrea Harzstark, MD, with colleagues at GE Healthcare)

- Discovered a new stem cell in the developing human brain that accounts for the dramatic expansion of the region in the lineages that lead to man. Further studies of these cells are expected to shed light on autism, schizophrenia and malformations of brain development, including microcephaly, lissencephaly and neuronal migration disorders, as well as age-related illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease. (Arnold Kriegstein, MD, PhD)

- Found that a single dose of radiation administered during surgery is as effective for patients with early forms of breast cancer as standard radiation therapy taking as long as six weeks. The finding is significant in both time and expense for patients. (Michael Alvarado, MD)

- Identified a molecular regulator (Hv1) that controls the ability of human sperm to reach and fertilize an egg, evidence that is key in both treating male infertility and preventing pregnancy. (Yuriy Kirichok, PhD)

- Determined that reducing salt in the American diet by as little as one-half teaspoon a day could prevent nearly 100,000 heart attacks and 92,000 deaths a year. (Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, with colleagues at Stanford University and Columbia University)

2009

- Reported the first direct evidence that a tiny filament extending from cells, known as primary cilia, may play a role in the most common malignant brain tumor in children and in a type of skin cancer known as basal cell carcinoma. The findings, conducted by two separate UCSF teams, suggest that drugs that boost or block primary cilia activity could offer a new strategy against cancer. (Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, PhD; and Jeremy Reiter, MD, PhD)

- Developed a new prostate cancer risk assessment test that gives patients and their doctors a better way of gauging long-term risks and pinpointing high-risk cases. The test, known as CAPRA, predicts the incidence of bone metastases, prostate cancer deaths and deaths from other causes. (Matthew R. Cooperberg, MD, MPH)

- Discovered the first gene involved in regulating the optimal length of human sleep, which is critical to human physical and mental health. The discovery is significant for future development of interventions to alleviate pathologies associated with sleep disturbance. (Ying-Hui Fu, PhD)

- Found that simple, inexpensive, high-flow oxygen is an effective treatment for cluster headache pain, providing relief for the disorder without drugs and their potential side effects. (Peter Goadsby, MD, PhD)

2008

- Performed the 10,000th procedure in the UCSF Organ Transplant Service, one of the largest and oldest in the world. Founded in the 1960s, the service now includes heart, intestinal, kidney, liver, lung and pancreas transplants. UCSF pioneered many advances in the field, and the UCSF service is recognized as the gold standard for other transplant centers. (Nancy Ascher, MD; John Roberts, MD; and Charles Hoopes, MD)

- Reported new data showing how language is organized within the cortex of the human brain, making it possible to use an innovative technique called negative brain mapping to safely remove tumors near language pathways of the brain. The technique minimizes brain exposure and reduces the amount of time the patient must be awake during surgery. Since the mid-1990s, a UCSF team has conducted pioneering work in brain mapping, a specialty within the neurosciences in which the neurophysiological properties of the brain are charted. (Mitchel Berger, MD)

- Reported that paramedics equipped with pre-hospital electrocardiographic (ECG) devices that wirelessly transmit critical information to emergency rooms while in route to the hospital can reduce the time it takes to diagnose and treat heart attack patients by more than 30 percent. The time reduction is linked to survival and lower risk of permanent heart muscle damage. (Barbara Drew, RN, PhD)

2007

- Identified several new genes associated with increased risk of heart attack, suggesting the existence of some previously unrecognized mechanisms and potential new strategies for risk reduction. (John Kane, MD; and Mary Malloy, MD)

- Determined that smoked cannabis reduces pain caused by HIV-associated neuropathy, the first measurable benefit for medical marijuana shown in a gold standard, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. (Donald Abrams, MD)

2006

- Determined that high-calorie, low-fiber Western diets promote hormonal imbalances that encourage children to overeat, thereby fueling the epidemic of pediatric obesity, now the most commonly diagnosed childhood ailment. (Robert Lustig, MD)

- Reduced the incidence of malaria to almost zero (by 97 percent) among children with HIV in Uganda by administering prophylactically an inexpensive antibiotic and providing insecticide-treated mosquito nets for coverage while sleeping. (Diane Havlir, MD)

2005

- Found that eating lots of fruits and vegetables, especially vegetables, is associated with a 50 percent reduction in the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. (Elizabeth Holly, PhD, MPH)

2004

- Discovered a ribbon of neural stem cells that potentially could be used to develop strategies for regenerating damaged brain tissue – and that could offer new insight into the most common type of brain tumor. (Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, PhD)

2002

- Developed the ViroChip, a microarray that contains DNA from every known virus and has proven to be a valuable experimental diagnostic tool for identifying previously unknown viruses in both humans and animals. The tool was first used in 2003 to confirm the identity of the virus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome, known as SARS, as a new corona virus. The technology later became the basis for the UCSF Viral Diagnostics & Discovery Center, as a resource for researchers worldwide. (Joseph DeRisi, PhD, and Don Ganem, MD)

- Demonstrated through clinical trials that a new immunosuppressive drug successfully halted the progression of type 1 diabetes. (Jeffrey Bluestone, PhD, who developed the drug in the 1980s before joining the UCSF faculty)

Jeffrey Bluestone, PhD, an international leader in immunotherapy, is executive vice chancellor and provost at UCSF.

Jeffrey Bluestone, PhD, an international leader in immunotherapy, is executive vice chancellor and provost at UCSF. -

Identified (2002 and 1997) receptors in cells of the peripheral nervous system that play key roles in the body’s ability to sense heat and cold, providing major insights into how the body experiences painful stimuli and temperature and produces pain hypersensitivity. The findings are valuable for future development of pain therapeutics. (David Julius, PhD)

- Designed a model California consumer information system website for the California Healthcare Foundation for evaluating the quality of care in nursing homes. (Charlene Harrington, RN, PhD)

2001

- Created two of the first human embryonic stem cell lines in the world, enabling scientists to study how stem cells might be used to treat such diseases and disorders as cancer, heart disease, diabetes and birth defects. (Roger Pedersen, PhD)

- Demonstrated that low tidal volume (LTV) ventilation is superior to the standard method of inflating the lungs in patients who are suffering from potentially fatal adult respiratory distress syndrome and are supported on a ventilator. The finding improved recovery chances and decreased mortality. (Michael Matthay, MD)

- Reported a landmark study showing that less invasive computer tomographic (CT) colonography, known as virtual colonoscopy, is effective for the detection of premalignant colorectal polyps and cancer. (Judy Yee, MD)

- Determined that chronic pain is a medical condition and not just a symptom, leading to improved strategies of management. (Christine Miaskowski, RN, PhD)

2000

- Discovered a pain relief strategy that could provide a long-sought alternative to morphine, without the drug’s addictive quality. The finding provided a window into the complex way in which opioids act on the pain-modulating circuitry in the body and how people experience pain. (Jon Levine, MD, PhD)

1998

- Identified two molecules that cause cells to induce asthma, a finding that paved the way for developing more effective drugs for treatment. (David Corry, MD)

1997

- Demonstrated that inflammation and the overproduction of IgE, a natural immunoglobulin, are a key cause of allergic asthma attacks. The proof-of-concept studies led to an entirely new class of asthma drugs. (Homer Boushey, MD)

1996

- Identified (1996 and 1989) new methods for studying the motility of single molecule motor proteins in cells and determined that two major motor protein families (kinesin and myosin) have similar atomic structures and operate by similar principles. Motor proteins are vital to normal cell function, and the findings are significant for understanding the molecular basis of cell division, transport within nerve cells, and muscle contraction. (Ron Vale, PhD, who was involved in the 1985 discovery of kinesin before joining the UCSF faculty)

- Determined that interventions to reduce emotional stress in heart disease patients and their family members have direct impact on reducing incidence of sudden cardiac death among these individuals. (Kathleen Dracup, RN, DNSc, dean emeritus, UCSF School of Nursing)

1993

Cynthia Kenyon, PhD

Cynthia Kenyon, PhD

Discovered genes that can double the lifespan of the roundwormC. elegans. These genes encode components of a conserved hormone signaling pathway, and have now been linked to exceptional longevity in flies and mammals, including humans. (Cynthia Kenyon, PhD)- Discovered the regulatory machinery of the “unfolded protein response,” a signaling pathway that controls protein folding in the cell. Proper protein folding is necessary for signaling between cells and healthy cell function, and disruption of this process is associated with numerous diseases, including cancer, diabetes, cystic fibrosis and vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Followup studies have focused on elucidating the mechanism by which the unfolded protein response operates, which is key to understanding its role in development of disease and of potential treatments. (Peter Walter, PhD)

1991

-

Shaun Coughlin, MD, PhD

Shaun Coughlin, MD, PhDDiscovered and cloned the platelet thrombin receptor that regulates blood clotting. The finding enabled the development of a new and potentially revolutionary class of clot-preventing drugs. (Shaun Coughlin, MD, PhD)

1990

- Patented a simple, cost-effective way to manufacture human proteins in yeast for therapeutic purposes. (Ira Herskowitz, PhD)

- First to use the X-ray structure of HIV protease to identify an inhibitor that effectively blocks the enzyme’s activity, the same method used today to design protease inhibitor drugs. (Charles Craik, PhD)

1989

- Devised a tool, now in wide use, for assessing pain and evaluating the effectiveness of medication in relieving pain in adolescent and pediatric patients. (Marilyn Savedra, DNS)

1985

- Discovered telomerase, a novel enzyme that plays a key role in normal cell function, cell aging and most cancers. The finding sparked a whole new field of inquiry into treatment of age-related diseases and cancer. The research team received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in recognition of the discovery. (Elizabeth Blackburn, PhD, with colleagues Carol Greider of Johns Hopkins University and Jack Szostak of Harvard Medical School)

1984

-

Keith Yamamoto, PhD

Keith Yamamoto, PhD

Installed the first cine-CT imaging device, which made it possible for the first time to image the beating heart. The technique was advantageous for detecting heart pumping and circulatory problems. (Doug Boyd, MD) - First to clone a receptor for steroid hormones, a major first step in understanding how these essential signals govern processes as complex as metabolism and reproduction. This achievement and subsequent research made glucocorticoids the most completely understood of any hormone system and its receptor the best understood human gene regulatory factor, which provided key knowledge for development of new treatments for a wide range of diseases. (Keith Yamamoto, PhD)

- First to describe a disease known as hairy leukoplakia, often the first sign of AIDS. (John Greenspan, BDS, PhD; and Deborah Greenspan, BDS, DSc)

1983

- Co-discovered the AIDS virus – known as HIV, human immunodeficiency virus – originally calling it AIDS-related retrovirus. (Jay Levy, MD)

- Produced clear, dramatic images of the soft tissues of the body, using nuclear magnetic resonance (now known as MRI). UCSF researchers went on to direct some of the first clinical placements in the country of devices that provided the images. (Leon Kaufman, PhD; and Larry Crooks, PhD)

1982

- Discovered prions, an entirely new biological principle of infection and disease, which cause degenerative brain disorders, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in people and mad cow disease. The discovery was honored with the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. (Stanley Prusiner, MD)

- Discovered that AIDS could be transmitted through blood transfusions, and were first to warn the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the finding. The discovery and its impact on the safety of the nation’s blood supply led to new methods of screening donors and saving lives. (Arthur Ammann, MD; Diane Wara, MD; and Morton Cowan, MD)

1981

- Performed the first successful open fetal surgery, in which a surgical team corrected a life-threatening birth defect in the fetus while it was positioned in the mother’s uterus. The entire field of fetal treatment was pioneered at UCSF, which has more experience in this specialty than any other institution in the world. (Michael Harrison, MD; Mitchell Golbus, MD; and Roy Filly, MD)

- Performed the first catheter ablation in a human to correct heart rhythm problems without open heart surgery. UCSF is credited with pioneering the procedure through extensive studies. (Melvin Scheinman, MD)

- Cloned the gene for the outer coat of the hepatitis B virus, making possible the development of the first-ever vaccine using recombinant DNA techniques. Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1986, the vaccine has had significant impact on world health, including the incidence of liver cancer. (William Rutter, PhD)

- Co-discovered embryonic stem cells in mice and coined the term embryonic stem cells, laying the groundwork for worldwide research on human embryonic stem cells to treat disease. (Gail Martin, PhD)

1980s (early)

- First to identify an association between HIV/AIDS and malignant lymphomas, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma, which are cancers of the lymphoid tissue. (John Ziegler, MD, MSc, who did pioneering work in development of a cure for Burkitt’s in children in Africa before joining the UCSF faculty.)

- Created the first-of-its kind computer program called DOCK to predict which off-the-shelf chemicals might bind to specific proteins and other molecules of interest. Rich visual displays of these computer-screening results can be rotated in three dimensions to help stimulate new ideas about how molecules are likely to interact, including ideas that may lead to new drugs. The program went on to become widely used by researchers. (Irwin Kuntz, PhD)

- Conducted groundbreaking studies on the importance of gender-based health care research that was instrumental in shaping the field of women’s health. (Virginia Olesen, PhD)

1980

John Clements, MD. Developed an artificial form of the natural lung secretion called surfactant, revolutionizing treatment for premature infants and significantly reducing infant deaths worldwide. The drug therapy compensates for the absence of the substance in infants born with immature lungs. It was developed by a UCSF team following a decade of work (1961-1972) in the initial discovery and characterization of surfactant. (John Clements, MD; William Tooley, MD; and Roderic Phibbs, MD)

John Clements, MD. Developed an artificial form of the natural lung secretion called surfactant, revolutionizing treatment for premature infants and significantly reducing infant deaths worldwide. The drug therapy compensates for the absence of the substance in infants born with immature lungs. It was developed by a UCSF team following a decade of work (1961-1972) in the initial discovery and characterization of surfactant. (John Clements, MD; William Tooley, MD; and Roderic Phibbs, MD)- First to report that elevated blood sugar caused abnormal structures in cells, helping to pioneer the intensive glucose control strategies now used throughout the world for managing diabetes. (John Karam, MD, and Gerold Grodsky, PhD)

1979

- Cloned the gene for human growth hormone, setting the stage for synthetic human growth hormone created through recombinant DNA technology. (John Baxter, MD)

- Developed a cochlear implant device that enables the deaf to hear. (Michael Merzenich, PhD; Robert Schindler, MD; and Robin Michelson, MD)

- Cloned bovine growth hormone, a discovery with significant implications worldwide. Bovine growth hormone has been used to increase milk production in cattle and has become an important part of food supply and economies, particularly in developing countries. (Walter Miller, MD)

1978

- Discovered that placebos work in part by activating the endorphin system, the body’s natural pain control network. (Howard Fields, MD, PhD; Jon Levine, MD, PhD; and Newton Gordon, DDS)

- Co-discovered a protein kinase that is a product of proto-oncogenes, normal genes that can be converted to cancer genes by genetic damage. The kinase is an enzyme that alters the function of many other proteins by attaching phosphate groups to them, and the finding was the first identification of a molecular mechanism involved in tumorigenesis, the process of tumor formation. The discovery led to a significant new field of study focusing on protein kinases, which now represent the largest group of targets for new cancer therapeutics. (Arthur Levinson, PhD; J. Michael Bishop, MD; and Harold Varmus, MD)

1977

- Isolated the gene for insulin, leading to the mass production of genetically engineered insulin to treat diabetes. This research achievement is recognized as the first major triumph using recombinant DNA technology. (William Rutter, PhD)

- Developed liposomes, microscopic sacs that can safely transport drugs within the body. (Demetrios Papahadjopoulos, PhD)

1976

- Developed the first prenatal tests for inherited blood diseases such as sickle-cell anemia and thalassemia. (Y.W. Kan, MD, DSc)

- Discovered proto-oncogenes, normal genes that can be converted to cancer genes by genetic damage. The finding led to recognition that all cancer probably arises from damage to normal genes, and provided new strategies for the detection and treatment of cancer. The research team received the 1989 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in recognition of the discovery. (J. Michael Bishop, MD; and Harold Varmus, MD)

- Discovered a drug therapy that could correct a common cardiovascular defect in premature infants, called patent ductus arteriosis, thereby allowing babies to avoid major surgery to correct the problem. The therapy was based on indomethacin, a common anti-inflammatory drug. (Abraham Rudolph, MD; and Michael Heymann, MD)

1974

- Used a breakthrough technique called deep brain stimulation that involved inserting an electrode deep in the brain to activate the body’s own pain control centers, thereby relieving chronic, debilitating pain. (John Adams, MD; and Yoshio Hosobuchi, MD)

- Discovered chlamydia as a primary cause of pneumonia in newborns, which sometimes leads to permanent lung damage. The finding led to the determination that a routine test in the expectant mother could allow for immediate antibiotic treatment to prevent nearly all related lung disease cases in newborns. (Julius Schachter, PhD)

1973

-

Herbert W. Boyer, PhD

Herbert W. Boyer, PhD

Achieved the first successful DNA splicing, a discovery that spawned the entire biotechnology industry and has led to development of numerous lifesaving treatments. (Herbert Boyer, PhD, with colleague Stanley Cohen of Stanford University)

1971

- Synthesized human growth hormone, making possible later development of successful treatments for childhood growth disorders. The achievement followed three decades of UCSF work that focused on identifying and isolating the hormones of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. (Choh Hao Li, PhD)

- Developed a ventilation technique called continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to treat newborns suffering from lung failure. A lifesaving technique, the procedure was gentler on the lungs than other types of ventilation, and became the most widely used mode of care employed for very premature babies throughout the world in neonatal intensive care units. (George Gregory, MD)

1966

- Developed an innovative program that positioned pharmacists as “clinical pharmacists” who were active members of the health care team, working side by side with physicians and nurses to provide direct care to patients. The first of its kind in the United States and considered revolutionary, the program was based on training pharmacists as drug therapy specialists, and not simply drug dispensers. The pioneering UCSF work led to clinical pharmacy as a distinct health sciences specialty. (Jere Goyan, PharmD; Eric Owyang, PharmD; Sidney Riegelman, PharmD; and Donald Sorby, PhD)

1963

- First to link obesity to type 2 diabetes, a finding that resulted in revolutionary changes in diabetes treatment and prevention. (John Karam, MD; and Gerold Grodsky, PhD)

1923

- Discovered vitamin E. (Herbert Evans, MD, during the period when the basic science departments were based at UC Berkeley)

1920s

- Developed basic sterilization and hygiene procedures for the US canning industry to prevent botulism, thereby safeguarding consumers and saving the industry. (Karl F. Meyer, DVM, PhD)

1914-1921

- Conducted initial studies on liver metabolism and the relationship between the liver and blood components, leading to successful treatment of pernicious anemia, a usually fatal form of the disease. The research was conducted at the George Williams Hooper Foundation, located on the Parnassus campus. (George Whipple, MD, who left UC in 1921 for the University of Rochester. He and Harvard colleagues George Minot and William Murphy received the 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their body of research that led to the lifesaving treatment.)

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Community Overview.

Serving the community has been ingrained in the ethos of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) since the early days of treating neighbors in need after the great 1906 earthquake in San Francisco.

For nearly 150 years, UCSF has been an integral and important member of the community as a public university, primary health care provider and leader in life sciences research. UCSF forges many fruitful partnerships in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond to further its advancing health worldwide™ mission.

In fact, UCSF serves the community through numerous activities such as:

- Providing high-quality patient care at local hospitals and neighborhood clinics;

- Conducting life sciences research in cooperation with partners across the city and around the globe;

- Reaching out to students at all educational levels to advance knowledge and promote higher education;

- Partnering with institutions and organizations of all kinds to promote health, wellness and quality of life;

- Sponsoring social, recreational, cultural and educational activities that are open to the public.

High-school students, who are guided by faculty, graduate students and postdocs in the Department of Biochemistry, earned high praise in the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition.

The UCSF Strategic Plan, released in 2007, specifically calls on the University to serve the local, regional and global communities and eliminate health disparities, foster research collaborations and “promote civic engagement in all facets of activities at UCSF to strengthen partnerships between the campus and the community.

One of the longest and most successful partnerships is with San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH), where more than 2,000 UCSF physicians and staff work side-by-side with the dedicated employees of the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Teams at SFGH deliver around-the-clock trauma, psychiatric and emergency care, outpatient treatment and a wide range of other important medical services to everyone in San Francisco, regardless of their ability to pay. SFGH is also an essential training ground for future health care professionals and researchers.

One of the educational programs with the broadest impact in the community is the Science & Health Education Partnership (SEP), a collaboration with the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). Initiated in 1987, SEP enables UCSF scientists and educators to work with the SFUSD to support quality science education. Each year, more than 300 UCSF participants contribute about 10,000 hours of service, and work with more than 400 SFUSD teachers representing more than 90 percent of the K-12 public schools in San Francisco.

The UCSF Department of Dermatology provides free skin cancer testing every year.

Importantly, UCSF welcomes input from the community and provides opportunities for ongoing dialogue and collaboration in two major ways:

- The University Community Partnerships Office established in 2006, coordinates the many existing partnerships between UCSF-affiliated individuals or groups and San Francisco-based community organizations, and supports new partnerships.

- The UCSF Community Advisory Group (CAG), originally formed in 1992 as a program of Community and Government Relations is a conduit for direct dialogue with UCSF representatives. The CAG is made up of representatives from a wide range of neighborhood, civic, ethnic, labor and business groups who provide UCSF with their views regarding campus planning, land use and other issues.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Chancellor.

Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, MPH, a physician, pioneering cancer researcher and successful biotechnology industry executive, became chancellor of UCSF on Aug. 3, 2009.

Desmond-Hellmann is UCSF’s ninth chancellor and the first woman appointed to the top leadership post of the health sciences university. She holds an appointment as Arthur and Toni Rembe Rock Distinguished Professor. Desmond-Hellmann succeeded J. Michael Bishop, MD, a Nobel laureate who served as UCSF chancellor for 11 years.

Born in Napa, California, as one of seven siblings, Desmond-Hellmann calls herself a “small-town girl” at heart. She was raised in Reno, Nevada, where she spent time as a youngster in her father’s pharmacy, listening to his daily chats with family doctors, which sparked her interest in a medical career.

After earning a bachelor of science degree in premedicine and a medical degree at the University of Nevada, Reno, Desmond-Hellmann arrived at UCSF in 1982 as an intern, and said that the experience transformed her life.

Desmond-Hellmann completed her clinical training at UCSF, where she met her husband, and then served on the UCSF faculty as associate adjunct professor of epidemiology and biostatistics. She spent two years as visiting faculty at the Uganda Cancer Institute, studying HIV/AIDS and cancer.

Before rejoining UCSF as chancellor, she served as president of product development at Genentech, a position she held from March 2004 through April 2009. In this role, she was responsible for Genentech’s preclinical and clinical development, process research and development, business development, and product portfolio management. During her time at Genentech, several of the company’s patient therapeutics (Lucentis, Avastin, Herceptin, Tarceva, Rituxan and Xolair) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and the company became the nation’s No. 1 producer of anticancer drug treatments.

In November 2009, Forbes magazine named Desmond-Hellmann as one of the world’s seven most “powerful innovators,” calling her “a hero to legions of cancer patients.” The seven were lauded for their curiosity, empathy and leadership.

Her return to UCSF in August 2009 to take the helm was like a homecoming to the University that helped shape her, both personally and professionally, and to the San Francisco neighborhood where her father’s family first settled when they immigrated to the United States.

One of her favorite inspirational quotes from American inventor and businessman Thomas Edison sums up her own life: “If we did all the things we are capable of doing, we would literally astound ourselves.”

Desmond-Hellmann is board-certified in internal medicine and medical oncology, and earned a master’s degree in public health from the University of California, Berkeley.

Desmond-Hellmann signs the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Book of Members, a tradition dating back to 1780, after being inducted into the academy at a ceremony in October 2010.

> University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Budget.

The second-largest employer in San Francisco and the fifth-largest in the Bay Area, UCSF is a $3.6 billion economic engine that drives innovation in life sciences research and health care with worldwide impact.

From co-leading the birth of the biotech industry to bringing in the most funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of any public institution, UCSF is a successful enterprise that provides jobs and fuels the economy.

UCSF Projected Revenues, FY 10/11 total: $3.69 billion.

In fact, UCSF generates $4.9 million in direct revenues to the city of San Francisco’s general fund, for a positive net impact of more than $720,000 according to a 2010 Economic Impact Report.

While UCSF’s total budget was $3.6 billion in fiscal year 2010, the University generated almost twice that amount when including its operations, salaries, construction and student spending.

UCSF had an annual budget of $3.6 billion in fiscal year 2010,

including $1.9 billion generated by UCSF Medical Center.

UCSF Medical Center, which accounts for more than half, or $1.9 billion, of the University’s budget, pays its own way, and is bringing in millions of philanthropic and federal stimulus dollars to build a new hospital complex at Mission Bay. UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay, scheduled to open in 2014 to serve children, women and cancer patients, will also create about 2,000 jobs in construction, health care and other services.

Here are a few highlights about the UCSF budget:

- UCSF received close to $269 million in total private support in fiscal year 2010, marking the tenth consecutive year in which total private support to UCSF exceeded $200 million.

- UCSF received about $463 million in total NIH research support (including research and training grants, fellowships, and other awards) in fiscal year 2009, making it the top recipient among public institutions and the second-highest among all institutions nationwide.

- UCSF overall and each of its schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy have ranked among the top four in total NIH funding for more than a decade.